Meet the 'Last Chance U' adviser who gave troubled football players a second chance

Academic coach Brittany Wagner has a dozen former students in the NFL.

— -- Just hours before the big game, the football players at Madison Heights High School in Michigan were laser-focused on their new coach.

But Brittany Wanger doesn’t coach football, she helps young men win in the game of life.

The 39-year-old single mother boasts having helped turn a dozen of her former students into NFL players as a former academic adviser at East Mississippi Community College in remote Scooba, Mississippi. Players who don't make the cut at elite programs, because of bad grades, criminal records and other issues, attend the school in hopes of getting picked up. Wagner's efforts and the stories of some of these troubled players are documented in the series “Last Chance U.”

“We took chances on a lot of athletes, a lot of kids that nobody else would take a chance on,” Wagner said. “Nobody else wanted the stigma that went with taking kids with a record or taking someone with these deep academic or social issues.”

“Last Chance U” follows Wagner as she works with members of the football team. Her goal is to get them to graduate from the two-year community college and play ball at a four-year university. She said she helped 98 percent of her students graduate in just one year.

When asked if she thought student athletes get to live by a different set of rules than non-athletes, Wagner said she didn’t believe that was true.

“For some of them… football was the only, the only reason and the only opportunity that they have to be in college or to have a roof over their head,” she said. “And what, you take that away from them… and now what?”

De’Andre Johnson was one of those students at EMCC. The former Florida State quarterback made headlines in 2015 for punching a woman in a bar after a confrontation. He was 19 years old. He pleaded guilty to misdemeanor battery and was kicked off the team.

“I totally should have walked away,” Johnson told ABC News in a 2015 interview. “I’m sorry, if I could do it over again, I would.”

Johnson went on to graduate from EMCC and is now the quarterback at Florida Atlantic University, though he has been sidelined with injuries this season.

Wagner believes it’s a misconception that misbehaving athletes get away with more than non-athletes. For many, like 18-year-old defensive lineman Ronald Ollie, football is not just a game. It’s life.

Wagner said without football, she doesn’t know what Ollie would have done. Ollie, who appears on the show, lost his parents at a young age.

“His dad had pulled a gun on his mom and killed her and then turned around and killed himself,” she said. “I think when you experience that at that young age, I think you're just waiting for it to happen again and again and again, in your life. You're waiting for loss.”

As someone who grew up in a stable home, Wagner said she has a hard time understanding why some of these students are criticized for being troubled.

“We want to beat them up because they play football? Or because they make a mistake? It's a freaking miracle that they're even functioning at 18,” Wagner said.

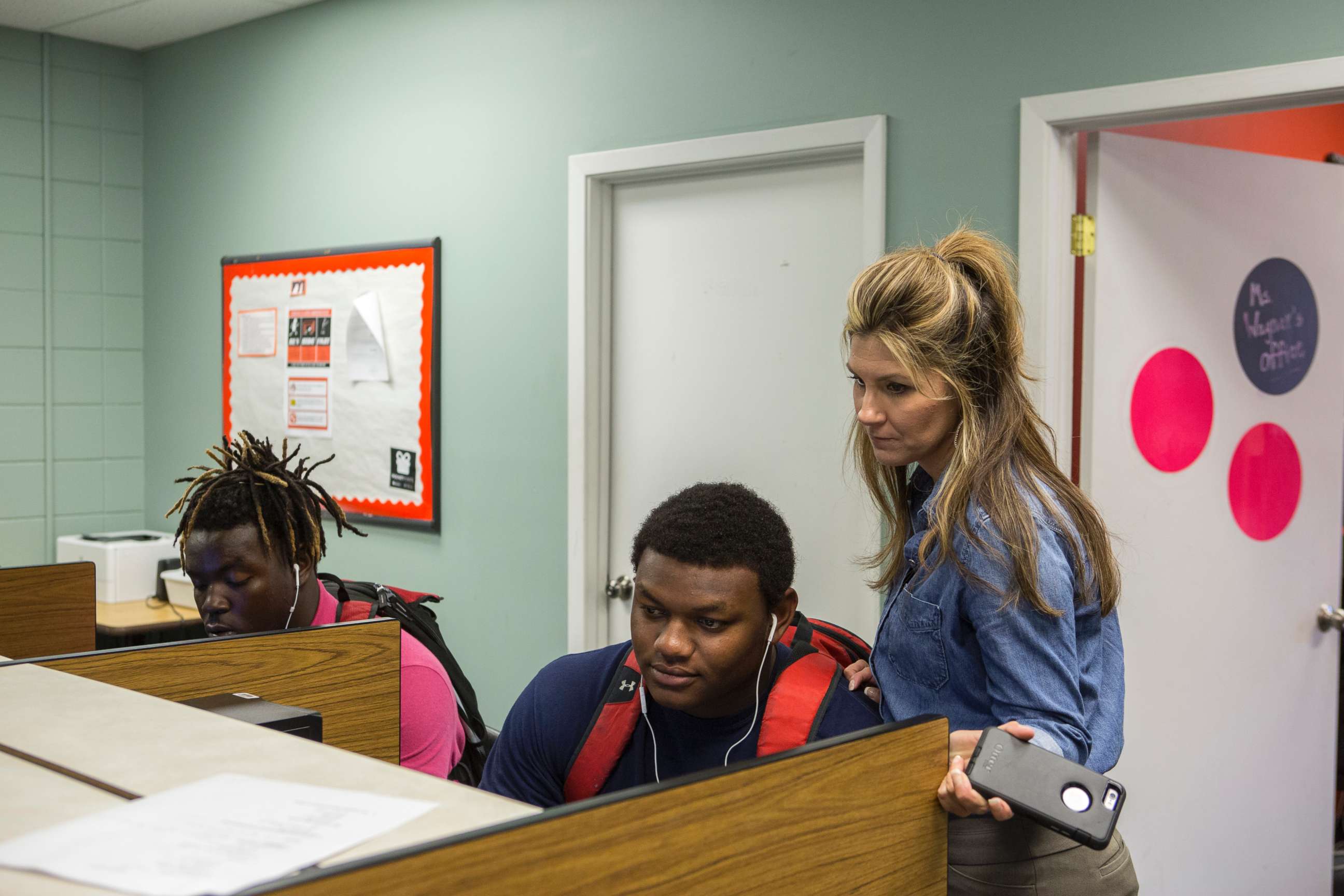

After eight years at EMCC, Wagner launched her own consulting company called 10 Thousand Pencils to help other advisers around the country. Her first stop was the Madison School District, just outside of Detroit, where she’s training teachers and counselors to work with student athletes like senior Dominik Rowell.

“My first time watching ‘Last Chance U,’ you looked at a lot of kids and you're like, same story, same story… here, just different states,” he said.

For Rowell, everything is riding on this football season. The team captain and middle linebacker, whose nickname is “Butter,” said this is his last chance.

“Football is my everything,” he said. “I’ve been playing this game since I was 8. And I’ve never loved anything more… so, football is my life.”

After some bad grades at his old high school, the 16-year-old had to petition to play football at Madison Heights High School. Rowell wanted to make good on his future for his 1-year-old son, Dominik Jr.

“[He] makes life better,” Rowell said of his son. “Sometimes you can get stressed about a lot of things. You can cry about a lot of things, but when I look at him and I see myself. It’s a little me.”

Rowell said he recently quit his job at a doughnut shop to focus on grades and football.

“I can't really buy my son much right now,” he said. I'm still trying to do the best I can. I just don't want him to ever feel like his dad don't love him.”

As for Rowell, in addition to having a young son to support, he said his own father recently went to prison, meaning he wouldn’t be around to cheer for him on the sidelines this football season. For Rowell, who said his father has always shown him a lots of love, that was incredibly tough.

His mother, Rachelle Rowell, advised him to take his frustrations out on the field.

“I think Dominik has played… phenomenally this year,” she said. “And I think it's because of the situation, like he's got something to prove… he wants his dad to be proud of him.”

Despite his odds, Rachelle Rowell is convinced her son will end up in the NFL.

“I'm so confident that he's going to make it, that I'm already planning, like, where I'm drafting. Are we going to do something at the house?” she said. “I’ve been saying this since he was 8. It’s not just because I’m blinded, because I know that things happen and he needs to have a back-up plan… I just have faith. I have faith in him, I have faith in our God that it’s going to happen.”

For Dominik, he said it’s either football or nothing. “I don’t have a plan B,” he added.

Wagner cautions players will eventually need to have another plan after their football career is over.

Randy Speck, the superintendent for Madison District Public Schools, was the one who gave Rowell his second chance.

“You cannot have success in an environment where kids are coming from challenging places without redemption. Without grace. You have to have it,” Speck said. “Then you’ll get all of those things that we measure successful schools by, you’ll get all of that, once you have a second chance.”

Speck said they brought in Wagner because they wanted her to work with struggling student athletes and get them back on track.

“I think if you understand relationships, and you understand connections, you will get results,” he said.

Wagner is working across the district, especially with at-risk students, and Speck credits those types of connections for an improvement in his district’s test scores. Counselors like Stacy Cauley said Wagner's advice has been working.

“We don't have, you know, anyone slipping through the cracks anymore and we don't have anyone that goes unknown,” Cauley said.

For Wagner, success is seeing the students she had worked with go on to get jobs and be flourishing members of society.

“I've had players call me and say, ‘Miss Wagner, I'm a truck driver, and you know what? I have insurance.' Success,” she said. “Miss Wagner… I teach biology at my high school and I'm coaching the quarterbacks at the school that I played at.’ Success.”

Wagner added, “I think you learn more in the losses in life than you do in the wins.”