The new faces of homeschooling: 3 families, 3 different approaches

Families are redefining what it means to be educated at home.

— -- Homeschooling is no longer just kids at home being taught by their mom or dad.

Homeschooling today takes place in co-ops, in homeschooling centers and even in some public schools as homeschooled kids are allowed to take part in sports and some classes.

"Good Morning America" is looking at the new faces of homeschooling in a two-part series led by Jessica Mendoza, an ESPN analyst and Olympic medalist who homeschools her eight-year-old son.

The percentage of students who were homeschooled doubled from 1999 to 2012, according to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES).

'I always thought I would educate my kids in public school, and have them in school their entire educational career.'

That increase leveled off in 2016, when about 1.7 million students, ages 5 to 17, were estimated to be homeschooled in the U.S. alone.

"I think what’s picked it up is people are now actually homeschooling for academic reasons, and that wasn’t true before," Dr. Joseph Murphy, professor of leadership and school improvement at Vanderbilt University, told ABC News. "Almost all the homeschooling was value-based, but now people are homeschooling to get their kids to learn more than they would in school."

There has not yet been a long-term "controlled study" to assess the growth of students who are homeschooled versus those who attend traditional school, according to Murphy.

"Homeschooling does very well compared to public schools, but the real question is where did the kid start and where did the kid end," he said. "A lot of the homeschool kids already started, six months or a year above the kids who are in public school, so that already explained why they’re more successful."

Tim Tebow sheds light on homeschooling, says it's 'good' to be 'different'

Homeschooling policies vary state by state, with fewer than half calling for homeschooled students' academic progress to be evaluated. Of the 20 states that do require evaluations, only 12 require standardized testing, according to the nonprofit organization the Education Commission of the States.

Most colleges, however, still require homeschoolers to take entrance exams such as the SAT or ACT, although some are adjusting their admissions policies to be more homeschool-friendly.

Three families across the country who represent the changing faces of homeschooling opened their doors to "GMA" to give a firsthand look at what their lives are like as homeschooling families.

'Now you see people from all walks of life that are homeschooling.'

The families include kids who went to traditional schools before turning to homeschool and others who have never stepped foot in a classroom. Some of the kids guide their own curriculum, while others take part in local homeschooling groups.

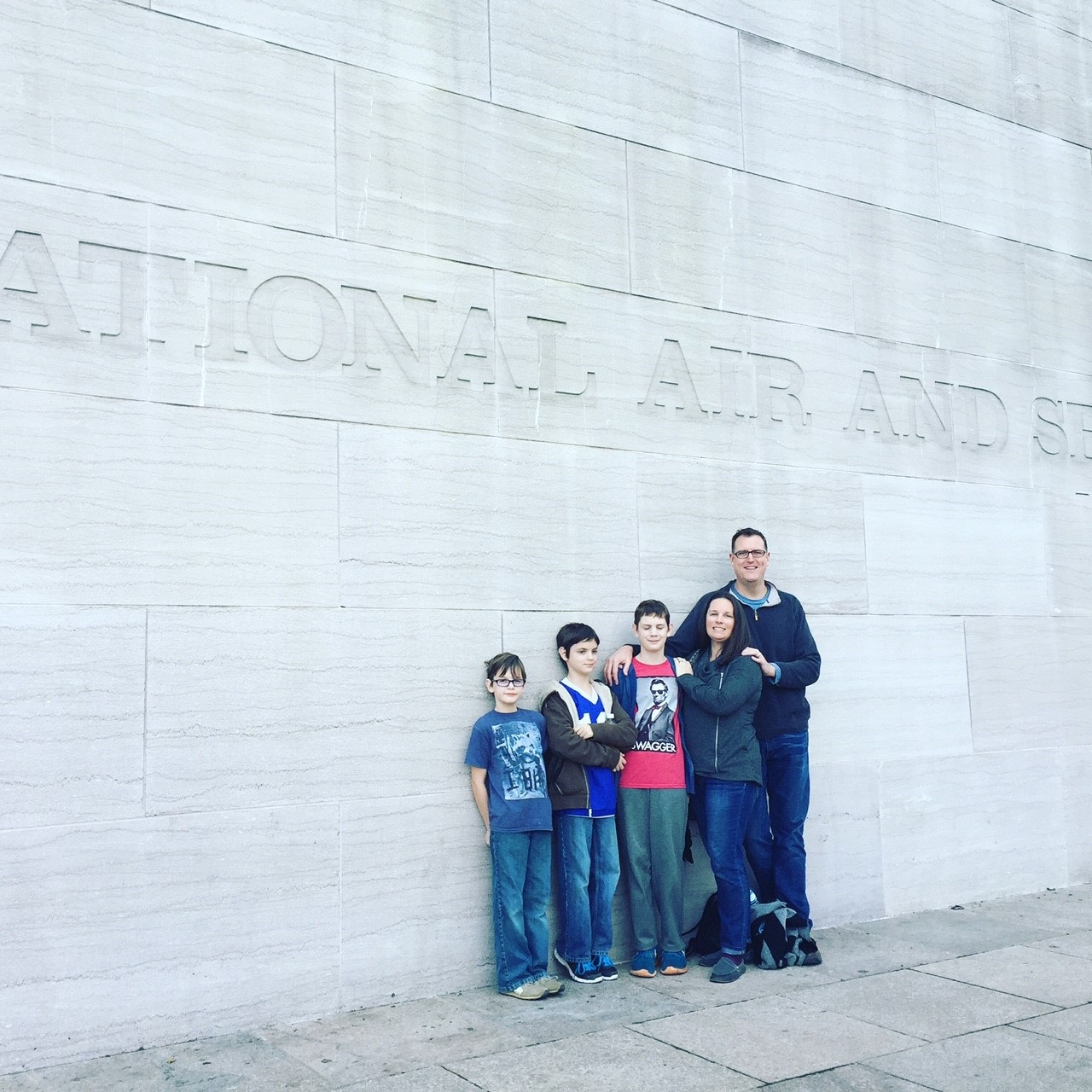

The Dillon family: 'Eclectic' homeschoolers

Beckett Dillon, 14, of Durham North Carolina, begins his school day around 10:30 a.m. Some days he might log online to take a virtual class or go to the website his family uses to chart their studies.

One day a week, Beckett and his brothers, Teague, 12, and Sullivan, 10, go to a local learning center that caters to homeschool families.

It’s all part of what Beckett’s mom, Anne Dillon, calls the family’s “eclectic” model of homeschooling.

“It probably looks a lot like what we in the homeschool world would call school at home, where you sort of do this, this, this and this,” she said. “We use a variety of resources which is why it would be called eclectic.”

Dillon and her husband, Dan Dillon, give their two youngest sons the freedom to look into whatever they’re curious about on their own for a period of time each week.

Beckett did the same in younger grades and said he appreciates the “sense of freedom” homeschooling provides.

“Homeschooling, there’s more, you do this, and you have a bit of break and you’ll do two things, and then there’s somewhat of a break,” said Beckett. “Public school was get to school, do this, do this, do this, do this, and then here’s your break and some homework.”

The Dillons began homeschooling their sons five years ago. Dan Dillon, a former public school teacher, said it was a path he and his wife did not expect to take.

“I always thought I would educate my kids in public school, and have them in school their entire educational career,” Dan Dillon said. “Anne and I got to talking about the opportunities that homeschooling would provide and off we went.”

He added of the traditional school model, "I felt like ... it could be potentially limiting to a student who has an interest in a particular idea or a particular subject but they just couldn’t pursue it because the model didn’t allow for that."

Sullivan, the Dillons' youngest child, likes to use his individual study time to bake. The brothers also take part in a writing class weekly at the home of another homeschool family.

On the first day of school one year, the Dillons toured Chicago instead of studying at home.

There was an adjustment period when the brothers got used to their mom as their teacher, but the Dillons now credit homeschooling with making theirs a “closer family.”

“We have dinner together every night. We get to travel at unusual times,” said Anne Dillon. “[The boys] are more like friends than I think they would be if they went to public school.”

The Hyson family: 'Whole-child' homeschoolers

A day of school for Uma Hyson, 8, and Charlo Hyson, 6, might include circus lessons, choir practice or a long walk in the woods near their home in Massachusetts, a state that does not require homeschooled students' academic progress to be evaluated.

Uma's and Charlo's parents, Sara and Charles Hyson, describe their approach to homeschooling as a "whole-child approach" that allows for "self-directed learning" where Uma and Charlo can choose to pursue their own interests.

"I think that our approach really fosters an intrinsic motivation, where our children delight in constructing things, exploring nature because we’ve created an environment that inspires awe and wonder," said Charles Hyson. "We're much more concerned about the whole child than can they divide fractions at a particular numeric age."

Charles Hyson is a public school teacher who chose a different path for his kids.

"I never had homeschooling as an ambition or an aspiration ... so it’s not that we’re homeschooling champions," he said. "It’s just that we feel there needs to be an evolution of mindfulness and consciousness in the public discourse."

Uma and Charlo spend time playing and studying on their own to help develop skills of self-awareness and self-resilience, according to their parents. Their school days are filled with "unstructured" time for them to explore.

"One of the criticisms I’ve heard of school is you’re in a class, you’re really engaged, you’re really interested, the bell rings and ... you just have to shift to whatever the next thing is," said Sara Hyson. "So you don’t really have the flexibility or the time or just the space to, like, keep going down that path as far as you want to."

The Hysons said one of the biggest misconceptions about homeschooling is the "lack of socialization."

"My best friend, who is Uma’s godfather, always expresses his concern about, 'Will they be sufficiently socialized?' and that has not at all been our experience," said Charles Hyson. "And the kids are in activities nonstop."

Uma and Charlo also socialize with neighborhood friends, who have introduced them to a staple of traditional schooling: homework.

"Our kids demand homework because the neighbors have homework," said Charles Hyson. "So they ask for math sheets, so we make them up, and they’re very capable."

"They kind of figure it out on their own and they have come up to be capable in all of the tasks that they’ve aimed for."

The White family: 'Un-schoolers'

On any given school day, the White siblings -- Nakiah, Samuel and Ava -- might be going to museums, watching YouTube videos, visiting a farm or baking cookies in their Dayton, Ohio, home.

Nakiah, 12, Samuel, 7, and Ava, 10, follow a practice of homeschooling dubbed un-schooling in which the world is their classroom.

"I consider un-schooling to be more of a lifestyle, because it’s not something we do Monday to Friday, from 7 a.m. to 3 p.m.," said their mother, Darcel White. "The learning never stops, it's continuous 24/7."

White, who educates her children on her own as a single mom, described un-schooling as "hands on."

"Instead of me going out and picking the curriculum for her and saying, 'This is what we’re going to do,' we are working together because that’s the type of relationship we have," she said. "I feel like that is the heart of un-schooling is parent and child working together to give them the best education possible."

When asked what her favorite part of homeschooling was, Ava said it is not having to sit at tables all day, "listening [and] about to fall asleep."

"I like learning about math," she said. "I like doing math and I like learning how to cook and how to make my own stuff."

White began homeschooling her children around seven years ago. Her oldest child, Nakiah, is dyslexic and has high-functioning autism, which played a role in White's decision.

"I thought, 'I have the opportunity to keep her as whole as possible,' so I thought, 'Well let me give this homeschooling a try and if it works, we’ll just keep taking it year by year,'" White recalled. "I went with my gut and it turns out that I was right and it’s been a great experience for the whole family."

White sees herself not as the teacher of her kids' homeschool, but as the "facilitator."

"I have our home set up in a way where there are things are things strewn about the house and the kids can easily access them, pick them up," she said. "We don't really have typical days."

She continued, "Each child has their different needs ... I have fun watching them pick these things up and kind of go off on their own and I just kind of step in when they need me to help."

The Whites also take part in a co-op that allows them to join other homeschooled kids in different activities, whether field trips to local sites or going to each other's houses to learn about different topics.

White said she has seen a major change in homeschooling since she began in 2009, including her own changed perception.

"I personally, even back in 2009, [thought] that homeschoolers were weird and they just sat at home at the kitchen table doing book work," White said. "I didn’t want to replicate that and that was my vision of homeschooling."

She added, "Now you see people from all walks of life that are homeschooling."