In Chicago, Witnesses to Violence Turn to First Aid to Save Lives

FBI found violence levels in Chicago increased 24 percent last year.

— -- On a chilly Saturday, 20 volunteers sat in a movie theater-turned-church located on Chicago’s South Side, taking detailed notes on how to properly tie a tourniquet, take a pulse and stop the bleeding from a serious injury as part of the inaugural Chicago South Side Trauma First Responders Course.

The course is a first-of-its-kind for the city, which had 762 homicides last year, according to the Chicago Police Department.

For the volunteers, the violence and shootings that have plagued the city are not an abstract concept but a part of daily life.

One participant, Caleb Jacobs, 23, has a quarter-sized scar from where he was stabbed in his abdomen in downtown Chicago in April 2014. That night, with blood seeping through his shirt, Jacobs thought about an alien movie he had seen with his brother, he told ABC News.

“A part of the movie he was bitten by one of the aliens, and he took the tooth out, [blood] gushing out, and he just packed it with his shirt and put pressure to it,” Jacobs said, recalling a character in the film.

In order to save his own life, Jacobs mimicked the movie, lying down on the sidewalk to put pressure on the wound, and waited for help.

“The littlest things and sometimes the littlest information can be a big part of saving your life,” Jacobs said.

Dr. Mamta Swaroop, 39, a trauma surgeon at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, created the Chicago South Side Trauma First Responders Course and wants to give all trainees basic knowledge of what to do in a situation like the one Jacobs faced so that they don't have to rely on vaguely remembered movie scenes for medical guidance.

Swaroop came up with the idea for the course after having multiple patients bleed out to death before they could be saved at the hospital. She noticed many had wounds in their arms and legs that, if properly bandaged, may have been survivable.

“The worst thing in the world is when you have to tell families over and over and over again that there was literally nothing you could do for their family member,” she said.

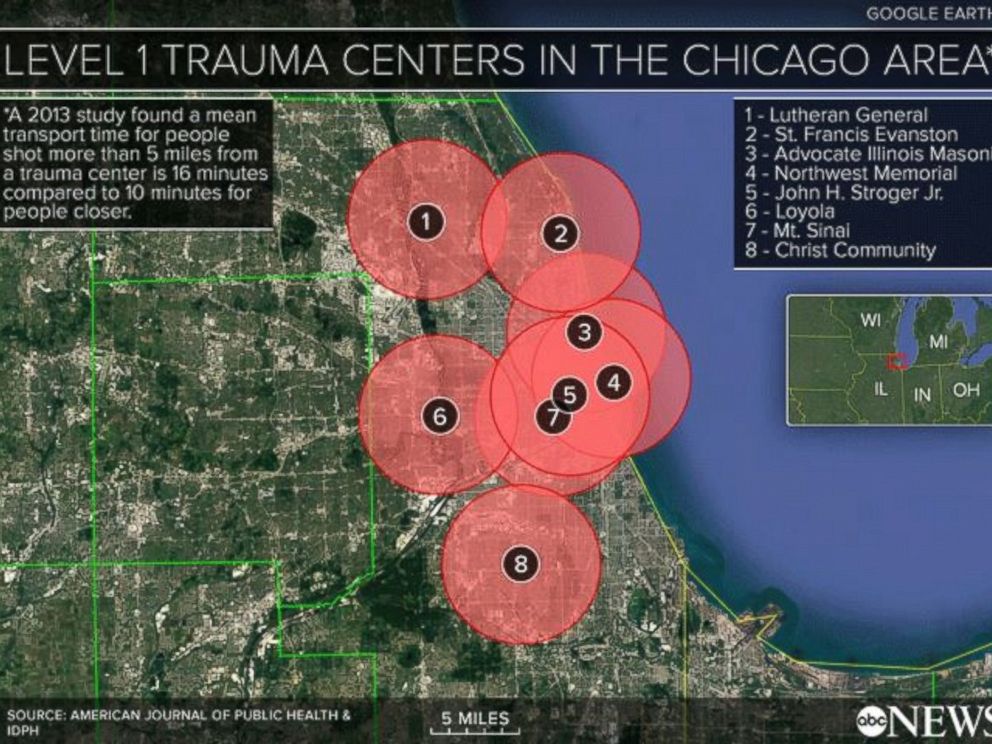

For years, many South Side residents have been frustrated by the lack of trauma centers in the area despite the high level of violence. While there are four level 1 adult trauma centers, designed to treat the most serious traumatic injuries, in Chicago itself and 19 total in Cook County, few are close to the southern portion of the county.

The average time for paramedics to arrive on the scene after getting a 911 call is six minutes, according to the Chicago Fire Department. But paramedics can be delayed if the police need to secure a scene, and it can take far longer to get a patient to a trauma center.

A 2013 study in the American Journal of Public Health examined data on 11,744 patients with gunshot wounds and found that 4,782 were shot more than five miles from a trauma center in the Chicago area. These patients had a mean transport time (from when the call came in to when they arrived in the hospital) of approximately 16 minutes compared to 10 minutes for people shot less than five miles from a trauma center.

Nearly one in five trauma patients in Chicago are “undertriaged” or going to hospitals not designated to treat their severe injuries, according to a study published earlier this month in JAMA Surgery. Co-author Lee Friedman explained this likely has to do with a lack of trauma centers in violent neighborhoods.

"People are being self-transported to these community hospitals ... it's not a failure of EMS," Friedman told ABC News in an earlier interview. "It's people saying, 'Let's get this person to [any hospital].'"

Swaroop doesn’t think her class will be the answer to the soaring numbers of victims or the long transport times. But she hopes to make a dent and empower residents to step up and save lives.

“I feel like this course is a Band-Aid,” she explained. “'Til the infrastructure, 'til the city, 'til everything else catches up. This is something that can be a stopgap.”

To ensure the course addresses the needs of people who live in these dangerous areas, Swaroop partnered with Cure Violence/CeaseFire Illinois, a violence prevention initiative that hires and works with people in the most violent neighborhoods to prevent further violence from occurring. She worked with the initiative to design the course and find people willing to come in on a Saturday to learn first-aid techniques.

LeVon Stone, the director of CeaseFire Illinois, said in some areas shooting or stabbing victims are often driven more than eight miles in order to reach a level 1 trauma center.

“We knew there was a need for someone to have some type of training,” Stone said. “[If] something was to happen in the community, they could possibly help save a life.”

During the first session earlier this month, Swaroop, along with other doctors and nurses from Northwestern Memorial Hospital, gave training on how to clear airways, move injured people from a busy intersection and minimize bleeding. But they also listened to the stories of the community members, many of whom have worked for years trying to reduce violence in their neighborhoods.

Priscilla Simes, a member of the regional grassroots social justice organization TARGET Area, recalled the moment a young man had been shot outside the organization's offices just yards from where the first responders class was now taking place.

“The only thing that I knew to do was to grab his hand and pray,” Simes said. “This class here, even with our own family, our own children, we’ll know what to do [now].”

At the end of the session, Swaroop gave out certificates and cards for everyone so that if they step in to help, they can give the cards to paramedics or police officers as proof of their training. When Jacobs came up, Swaroop gave him a big hug.

The night Jacobs was stabbed, he was taken less than two miles to Northwestern Memorial Hospital, where doctors including Swaroop were able to save his life. He ended up losing his spleen, pancreas and part of his colon. Despite all that, he said he's lucky he was stabbed less than two miles from the hospital.

“I could have got stabbed anywhere, but at least it was downtown ... at least I wasn’t here,” he said from his current home on Chicago’s South Side near Lake Michigan. He explained that if he had been injured in his current neighborhood, the ambulance would have had to travel nine miles to get to Northwestern.

If that had been the case, “I wouldn't be here,” he said.