Along North Korea's border with China, an uneasy alliance and a fear of war

ABC News traveled along the 880-mile border between China and North Korea.

— -- It was almost 65 years ago when North Korea and the United States agreed to a cease-fire. The guns stopped firing, and the planes stopped dropping bombs, but the war did not officially end. It was settled with an agreement, an armistice, that since 1953 has maintained a fully armed face-off along the 38th parallel. North Korean soldiers still stare at U.S. and South Korean forces across the 2-mile-wide Demilitarized Zone much as they have for decades.

The seesaw relationship between North Korea and the United States

To this day, North Korea is the most isolated country in the world. The DMZ, which divides North and South Korea, has gotten most of the media attention over the years, as it separates almost 28,000 U.S. troops from their enemies to the north.

I have been to North Korea eight times in the past 12 years, but on this trip, I wanted to explore the reclusive country's 880-mile border with China. The border largely follows two rivers: the Yalu in the south and the Tumen in the north. Both flow from the same source: a dormant supervolcano straddling the border — known to the Chinese as Changbaishan and to the Koreans as Mount Paektu.

It is a crucial trip because China is North Korea’s only remaining ally and never before has North Korea been such a threat. The country's mercurial leader, Kim Jong Un, is close to developing a nuclear missile capable of reaching the U.S. mainland. China could change this reality significantly.

The changing relationship with North Korea's lifeline

The relationship between China and North Korea has always been complicated. China's communist leader Mao Zedong famously said that the two countries were "as close as lips and teeth," a relationship forged in blood and steel during the Korean War against the United States.

It is true that these allies have stood side by side for many decades, but it is clear that their relationship is changing quickly — mostly since Kim took over from his father in 2011.

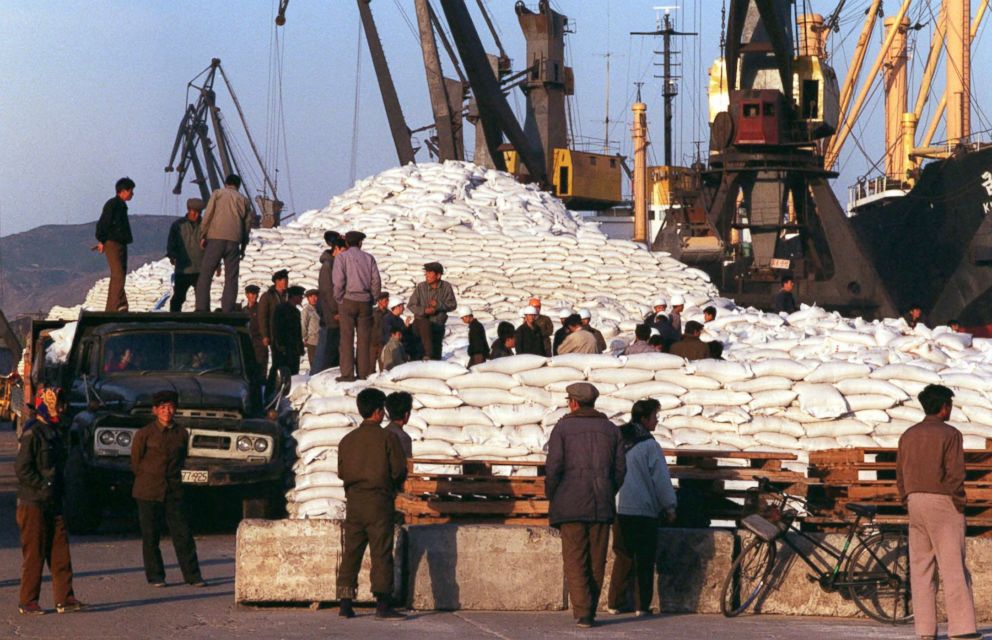

Economically, 90 percent of North Korea’s trade is with China, which means this border is the lifeline of the North Korean regime, a regime that China does not want to fall. The Chinese government fears that the sudden collapse of North Korea could spur a mass migration of people over the border, in a blow to China’s economy. More important, for all these decades, North Korea has served as a buffer for China, keeping U.S. and South Korean forces far from its own borders.

This 880-mile voyage along the border lasted six days and took us to five cities; it was filled with both beauty and unexpected moments.

We started in the city of Dandong, a bustling, unmistakably Chinese hub of commerce and condos on the southern end of the border. This is where the trucks and trains travel back and forth between the countries.

It’s also filled with Chinese tourists and about 40,000 North Korean workers, who spend years there without their families to learn Chinese and take money home when they return.

On assignment with ABC News' Bob Woodruff in North Korea

On another day, we watched Chinese military boats training on the river just a few feet from North Korea. Military guards lined the road, and people stopped their cars to watch. Our guides told us not to record video of North Korean land from our tour boat, lest we anger the soldiers who were carefully watching us from the other side.

During this trip, we heard firsthand about how the relationship between these close allies is quickly changing, largely because of North Korea’s unpredictable new leader. Along the border, Chinese people told us about their growing fears of a possible war. While most don’t believe China would be targeted by bombs or missiles, many told us they are very concerned that China’s economy will suffer if violence breaks out on the Korean Peninsula.

There is anger at the United States for irritating the North Koreans with U.S.–South Korean military operations. The Chinese people we spoke to along the border said they just want all that to end.

Hopes of reuniting someday

We visited many gorgeous places along the border, and perhaps the most impressive was Mount Paektu, which is considered sacred as the spiritual home of the Korean people. It is a volcanic mountain, geopolitically split in two at its crater. Some South Korean tourists we met there told us their hope is that the North and South will reunite someday and put an end to this ongoing war.

From this mountain, the melting glaciers pour into the Tumen River, which flows to the north. Half of China’s 2 million ethnic Koreans live in this region, and the river is narrower and shallower there, which is why more North Korean defectors choose to swim across to China.

In recent years there have been more reports of crimes committed by North Korean defectors, including theft and murder. In some cases, these crimes have also been committed by North Korean border guards, who are underfed and underpaid.

This region is close to North Korean nuclear sites where bombs have been tested. In Yanji, a city in the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture near the border, a high school security guard told us about how his school was evacuated after he and the students felt the earth shake.

A glimpse of a country its leader never wants anyone to see

Along the roads farther north, Chinese security rules got stricter. Tourism quickly disappeared, and more checkpoints lined the roads.

On three occasions, we were stopped by soldiers, police or state security agents. We were searched, questioned and finally urged to leave the region and return to Beijing.

Although I have been in North Korea multiple times, most of those visits were to the capital, Pyongyang, as well as a few trips to the North Korean side of the DMZ and one tour of a nuclear facility in Yongbyon.

But on those trips, I did not have the chance to speak with everyday people. Pyongyang is the country’s most advanced and modern city, home to the powerful and the elite, and there are virtually no opportunities there to hear from the poor and secluded who largely live in the countryside.

This trip along the border was, therefore, an opportunity to view the reclusive state through the lens of its neighbor and only supposed ally, China.

About 40,000 people have fled North Korea by defecting through this area. North Koreans desperate to leave don’t escape by crossing the heavily armed DMZ to the south. Instead, they flee to the northeast, where they can hide in the Chinese homes of ethnic Korean families. These families speak their language and understand their culture. They live in Chinese cities and villages where all the words on signs and buildings are in both languages.

As we endeavored to hear the stories of people living along this border, Chinese officials sometimes followed us. We were told that North Korean soldiers were watching us from across the water as well.

In spite of this, we had the chance to get a glimpse — from a different angle — of a country its leader never wants anyone to see.