Why the British Government Is Fighting to Stop Prince Charles’ Secret Letters from Publication

Battle over secret letters has gone on for nine years.

LONDON — -- When Prince Charles made rare public comments to criticize the lack of Shakespeare teaching in state school curricula, the British government was not too happy.

Now, it appears Prince Charles subsequently sent a letter to Britain's education minister of the time to apologize for not giving prior notice of his views and also to detail his perspectives on education policy, according to an ongoing case involving the government and a British journalist who filed a freedom of information request in 2005 to access the prince's correspondences.

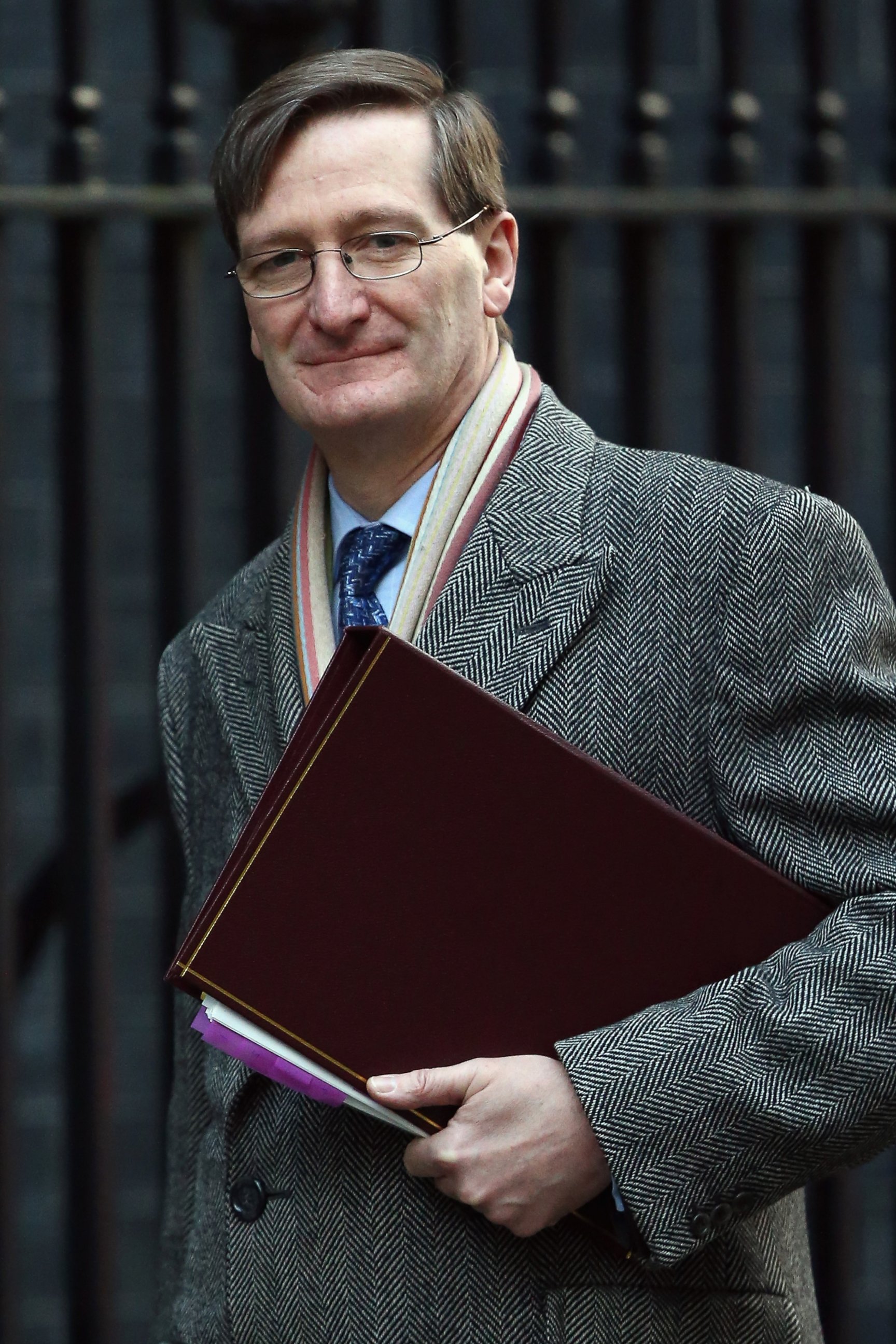

If the letters from Prince Charles to seven government offices are published, it could be a problem for the heir because it might jeopardize the throne's traditional political neutrality, according to former Attorney General Dominic Grieve. As attorney general, Grieve blocked an earlier court decision to reveal the letters, dubbed the "black spider memos" because of the prince's small writing.

The government has put up a tough fight for nine years against Guardian journalist Rob Evans to stop publication of the letters.

This week, hearings on the matter at the United Kingdom's Supreme Court could be the government's last fight.

"My request was driven by a wish for transparency," said Evans to ABC News. "The monarchy should be neutral. So, are they really?"

At the core of the case is whether public interest is sufficient to warrant publication of confidential letters, and who has the final word on what the public interest is.

"Confidentiality should be the starting point," said the Guardian's lawyer, Dinah Rose. "But an Upper Tribunal ruled that the public interest from a public figure was sufficient to overrule it."

"Advocacy letters are very different to personal letters," said Rose, who added Charles "sees himself as performing a public function."

Evans sought disclosure of a number of written communications between the prince and the following government departments between 2004 and 2005: Business, Innovation and Skills; Health; Children, School and Families; Environment, Food and Rural Affairs; Culture, Media and Sport; Northern Ireland and Cabinet Office.

When Evans' request was denied by the information commissioner, the journalist appealed to the Britain's Upper Tribunal. In Sept. 2012, the tribunal ruled that the Prince's communications should be disclosed to the extent that they fell into a category defined as "advocacy correspondence," according to legal documents seen by ABC News.

However, Grieve, who as attorney general was a member of government and had an advisory role, vetoed the court's decision. He said the public could interpret the letters to be disagreeing with government policy, which would be seriously damaging to Charles' role as a likely future monarch, according to legal documents.

The overruling of an independent and impartial court by a government minister is extremely rare in the U.K., and this week's hearing will determine whether he acted lawfully and on reasonable grounds.

The case addresses the question of whether public interest is best guarded by the judiciary or the executive branch of British government.

According to Rose, "Parliament has given little consideration" to the veto power given to an executive.

"The Upper Tribunal is much better equipped than a minister to make a decision," said Rose, adding a minister only gives "an opinion based on cabinet consultations."

The constitutional power to veto a court decision was given to the attorney general to protect the public interest where real and significant issues arise, said government lawyer James Eadie, who said it had followed a "carefully considered, deliberate decision" from parliament.

Prince Charles is known for his strong opinions on a range of topics from education to farming and health. Last week, The Guardian ran a long piece on how Charles would reset the sovereign's role by making heartfelt public interventions when he becomes king.