The 1972 Watergate burglary: How a piece of tape and an astute night watchman foiled the political crime of the century

Frank Wills was making his rounds on when he noticed something odd.

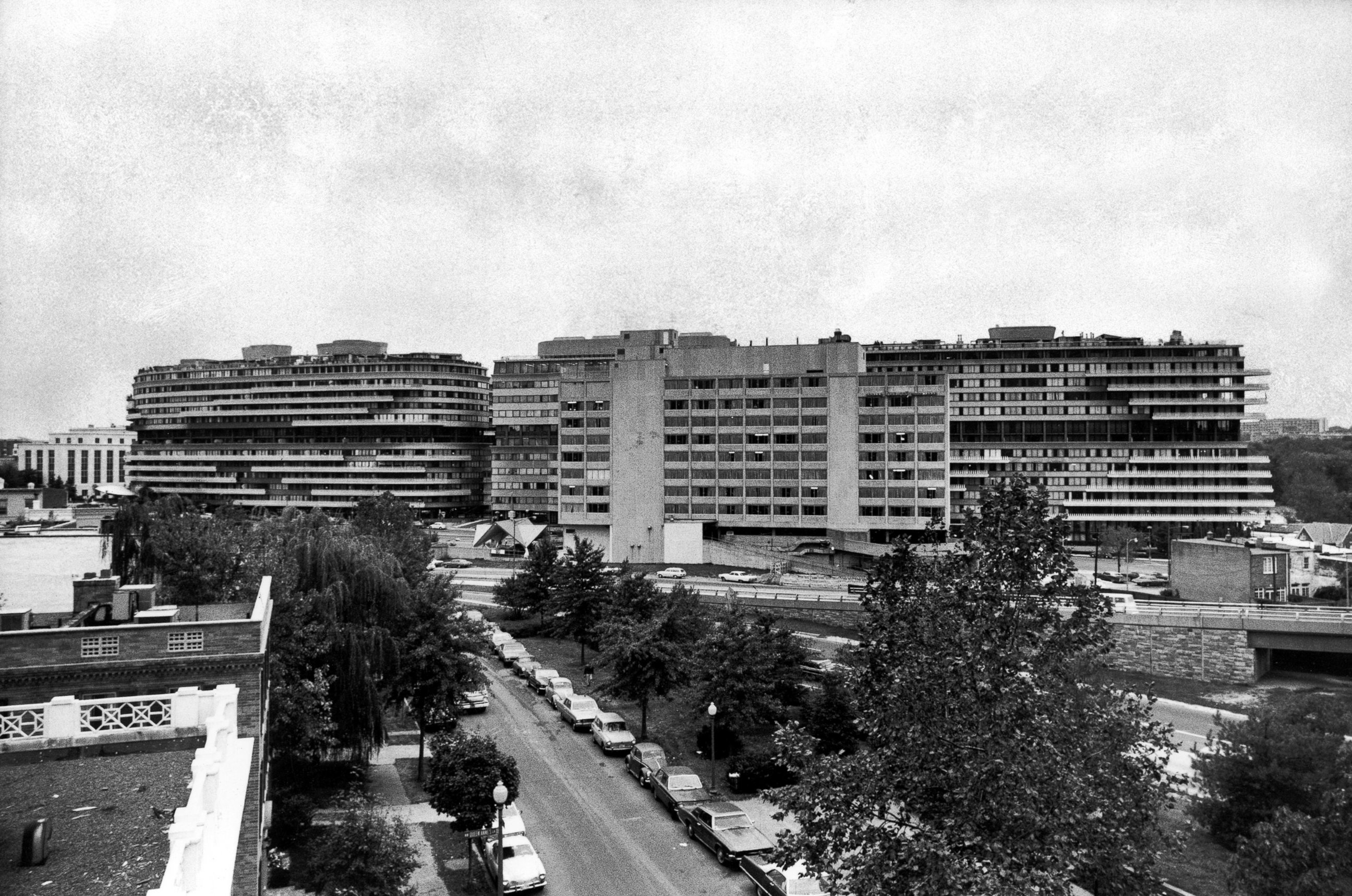

— -- Frank Wills, a night watchman at the Watergate office complex in Washington, D.C., was making his rounds on the night of June 17, 1972, when he noticed a piece of tape on the latch of a basement door in the complex’s parking garage.

“The tape, at first, didn’t seem to be anything unusual,” Wills in a 1973 interview with ABC News.

Wills, who died in 2000, said he removed the tape and continued his rounds. But when he came back around a little later, Wills noticed the door was taped again, preventing it from locking.

“At that time, I became a little suspicious,” he said.

What Wills didn’t know at the time was that he had stumbled upon the biggest political crime of the century.

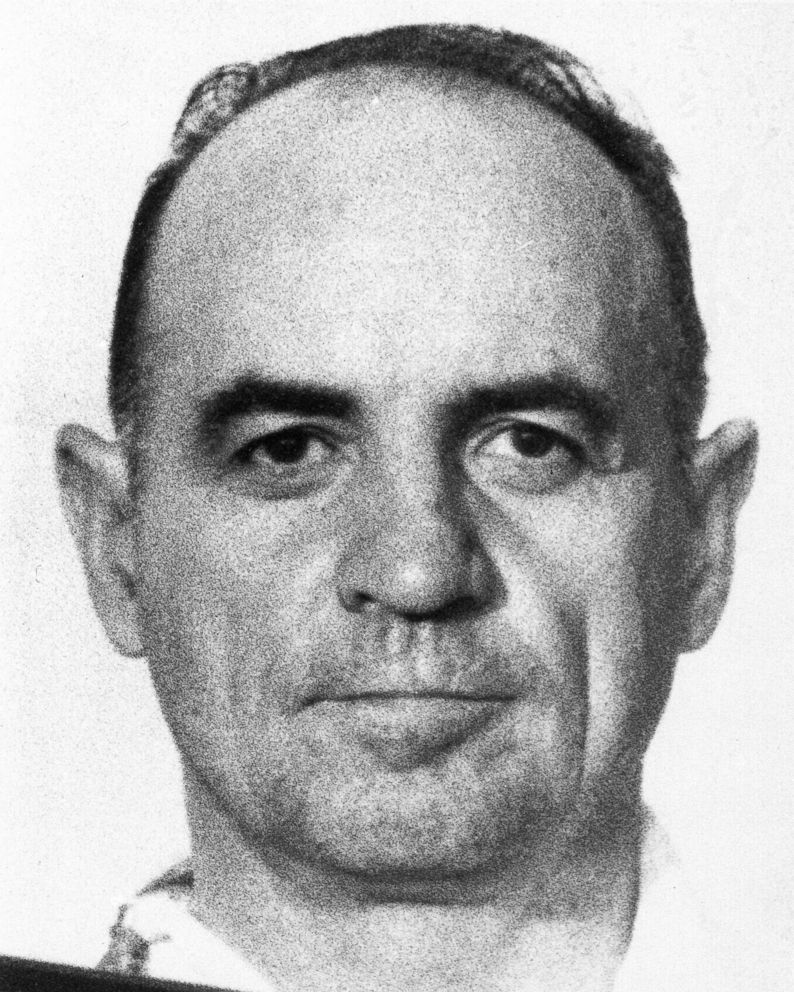

James McCord was the one who had placed the tape on the basement door, and tape was also placed on stairwell doors on the eighth and sixth floors of the building, the latter being the offices of the Democratic National Committee headquarters.

McCord, along with Bernard Barker, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez and Frank Sturgis, were the five men directed to break into the DNC’s offices at the Watergate complex to place bugging devices and take extensive photographs for Democratic Party documents.

The break-in was part of Operation Gemstone, a series of secret political tactics orchestrated by G. Gordon Liddy to gather negative intelligence on Nixon’s opponents.

It was almost 2 a.m. when Wills saw the door taped a second time. He called the police and reported a burglary.

D.C. Metro police officers John Barrett and Paul Leeper, who are now retired but worked in a plain clothes unit, responded to the call in an unmarked car without sirens. When they arrived at the complex, Barrett and Leeper went up to the guard station where Wills was sitting and Barrett said he showed his police badge.

“I had this old funky golf cap, I think I had just like a T-shirt underneath,” Leeper told ABC News.

“If a uniform car had answered that call, it could have been a whole different ball game,” Barrett added.

As Leeper and Barrett worked their way up through the building, they soon found the doors with tape on them.

"Our adrenaline is pumped," Leeper said.

Leeper said he kicked the door to the DNC offices open and Barrett pulled out his revolver.

“The desk was all ransacked and disheveled and messed up,” Barrett said. “As it turns out, probably every room in the DNC was like this, and we found out later that they were always messed up.”

What Wills, Leeper and Barrett didn’t know at the time was while McCord and the other four men were breaking into the building, they had a lookout named Alfred Baldwin with a transceiver and a clear view into the DNC offices across the street so he could alert Liddy if something went wrong. The only problem was, when the officers burst into the DNC offices, Baldwin was preoccupied.

“He was watching a show called ‘Attack of the Puppet People,’” Barrett said. “He was glued to the TV set … so he looked back out, he saw lights coming on [in] the DNC.”

In a 1994 BBC documentary, Baldwin said he noticed the lights on and he could see men wearing plain clothes. He radioed to Liddy and asked if McCord and the other men were dressed in business suits or casual clothing. When Liddy confirmed that their guys were wearing suits, Baldwin said he told him, “Well, we’ve got a problem.”

Leeper said if they had shown up in a marked police car, he and Barrett would have been in uniform that night and arrived with their lights on, which likely would have caught Baldwin’s attention and he could have alerted Liddy’s men before the officers could get upstairs.

But by the time Baldwin notified Liddy, Barrett said it was too late.

“We’re rolling down this hallway, checking the offices on both sides of the hallways… turning lights on, make sure that nobody’s hiding from behind us,” he said. “I was startled by an arm hitting next to the glass on the partition … it scared the living bejeezus out of me.”

When Leeper and Barrett shouted for the suspects to put their hands in the air, 10 hands went up -- the officers in plainclothes were facing a group of burglars in business suits.

“McCord said to me twice, he said, ‘Are you the police?’ And I thought, ‘Why is he asking such a silly question? Of course we're the police,’” Leeper said. “I don’t think I’ve ever locked up another burglar that was dressed in a suit and tie and was in middle age.”

But this was not a typical burglary.

“There were bugging devices … tear gas pens, many, many rolls of film … locksmith tools … thousands of dollars in hundred dollar bills consecutively ordered,” Barrett said.

According to the police report, the five burglars gave Leeper and Barrett false names and refused to give their ages the night they were arrested. The suspects had also used false names to book Rooms 214 and 314 at the Watergate Hotel to use as a base for the break-in.

Barker, Sturgis, Gonzalez and Martinez all pleaded guilty to charges involving conspiracy, burglary and wiretapping on Jan. 15, 1973. All served more than one year in prison and went on to live in Miami. Sturgis died in 1993 and Barker died in 2009, both of lung cancer.

Liddy and McCord were convicted on charges of conspiracy, burglary and wiretapping on Jan. 30, 1973. Liddy served 52 months in federal prison until President Carter commuted his sentence in 1977. After being sentenced to one to five years in prison, McCord only served four months after Judge John J. Sirica, who handled the Watergate case, reduced his sentence after he admitted the existence of a cover-up by officials high up in the White House. He later published a book called, "A Piece of Tape -- The Watergate Story: Fact and Fiction," and went on to live in Pennsylvania.