Scientists sound alarm over radiation in Nubian aquifer

But other experts say the health risk is unclear.

This is an Inside Science story.

People in Egypt's western desert are drinking groundwater with naturally high levels of radium, a radioactive element, according to research presented last week at the American Geophysical Union meeting in Washington. Experts disagree on the cancer-related health risks, but babies who rely on the most radioactive wells could get more than 100 times the maximum levels recommended by the World Health Organization for long-term exposure from drinking water, according to the researchers. Many communities across the Middle East and northern Africa are likely also using water with elevated levels of radiation.

Identifying the danger

Most people in Egypt get their water from the Nile River. But in the adjacent deserts and the Sinai Peninsula, people rely instead on groundwater, said Neil Sturchio, a geochemist at the University of Delaware in Newark, who conducted the study with graduate student Mahmoud Sherif. In many cases, this groundwater is pumped from an ancient reservoir called the Nubian aquifer -- a sandstone formation that extends some 2 million square kilometers (about 800,000 square miles) beneath Egypt, Libya, Chad and Sudan.

Long ago when the climate was wetter, water soaked into the pores of the now-buried sandstone, said Sturchio. The oldest water in the Nubian aquifer has been there for about a million years. It is a nonrenewable resource; the more people pump out, the lower the levels drop. But it is vast. The aquifer waters in Egypt alone would be enough to keep the Nile flowing for 500 years, according to Sturchio.

Sturchio and Sherif were inspired to test the Nubian aquifer after Avner Vengosh, a geochemist at Duke University, found high levels of radioactivity in a similar fossil aquifer in Jordan in 2009. These fossil aquifers are tempting resources for communities to tap because they contain fresh water that is low in most types of contaminants and disease-causing organisms. Vengosh initially assumed they would also be low in radioactive chemicals such as radium. Instead, he found radium levels up to 20 times higher than international standards.

Radium forms naturally from uranium and thorium in rocks, and it is removed when it binds to certain minerals. But in the studied aquifers, the types of minerals that remove radium tend to be scarce, said Sturchio.

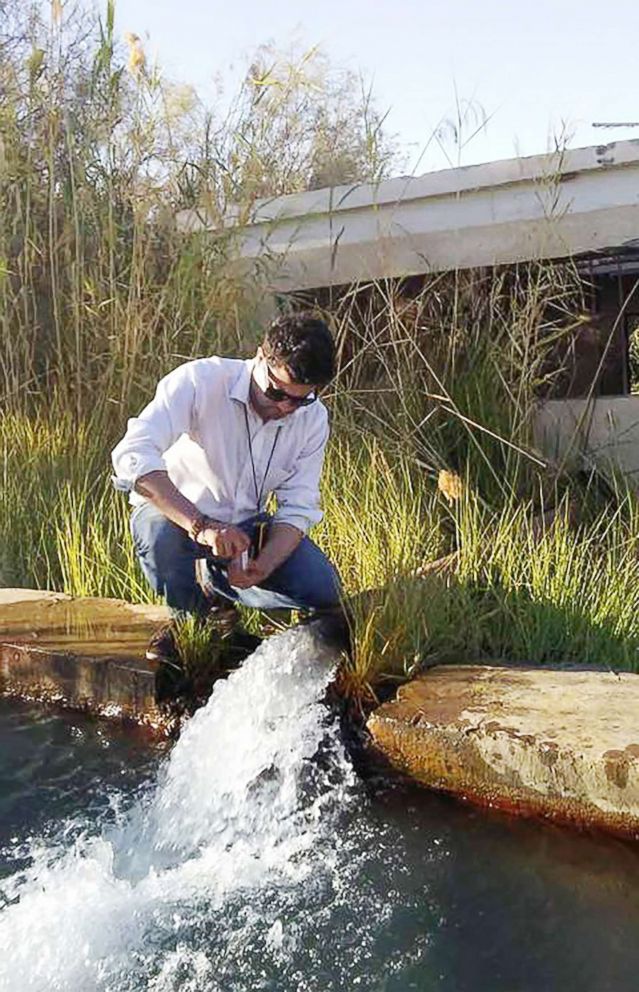

To see how widespread the radiation problem was, Sturchio and Sherif tested groundwater from sites across Egypt. They consistently found that radium levels in wells that tapped the Nubian aquifer exceeded safety thresholds set by the WHO. The deeper and more ancient the water, the more radioactive it tended to be, said Sherif.

The researchers published their findings from the eastern desert in 2017, and from the Sinai Peninsula in 2018. Last week they presented findings from 64 wells in the desert west of the Nile, which is drier than the other two regions and relies almost exclusively on the Nubian aquifer for irrigation and drinking water, said Sturchio.

In the western desert, the wells with both the highest and lowest radium levels came from the Bahariya Oasis, which lies about 230 miles southwest of Cairo and is home to 27,000 people. The WHO recommends that people take in no more than .1 millisieverts of radiation per year from drinking water. If people's drinking water contained radium levels equal to the average of all the Bahariya wells, an adult would be expected to take in about 5.4 times more than the WHO-recommended maximum, while a baby would take in about 54 times the WHO-recommended maximum, according to the researchers. Babies take in more radiation from the same water because they incorporate radium into their growing bones.

If a baby drank exclusively from the most radioactive well in Bahariya, it would be expected to receive nearly 138 times the WHO-recommended limit, according to the researchers' calculations. That's the radiation equivalent of nearly 690 chest X-rays or two chest CT scans per year.

And that's just from drinking water. People also use the water for irrigation, and radium can accumulate in crops and livestock, said Sturchio.

Unknown health impacts

Radium presents a potential health risk because as it decays, it produces ionizing radiation -- a high energy emission that can damage DNA and cause cancer. But to the best of Sturchio and Sherif's knowledge, there is no direct evidence that people who rely on the Nubian aquifer are getting more cancer than people elsewhere. Still, the researchers suspect that health impacts in those regions could go unrecognized. People who use the aquifer water are often poor and have little access to medical care, said Sturchio.

But Amal Ibrahim, a cancer epidemiologist at the National Cancer Institute at Cairo University and director of Egypt's National Cancer Registry, disagrees. While there may not be many hospitals in the western desert, he said, there are more than a dozen cancer care centers along the Nile that offer treatment free of charge.

"Once there are symptoms of cancer, people seek help," said Ibrahim. "And we give it to them."

Some parts of Egypt have elevated cancer rates due to hepatitis C, said Ibrahim, but so far he has seen no evidence for other regional differences in cancer rates. Still, he said, the radiation risk from groundwater deserves more study. He would like to see data on exactly how much aquifer water people are consuming, and whether the radium is making its way into crops, dairy products and bottled water.

Vengosh agrees that more research would be helpful, but he sees no need to wait before taking action to protect the public, either from the Nubian aquifer or from the Disi aquifer he studied in Jordan.

"There are several studies in the U.S. and Canada that show that communities that were drinking these types of water -- much lower [radiation] than what we see in Disi -- had elevated and high prevalence of cancer," said Vengosh. "We don't need to invent the wheel."

Marc Serre, an environmental geostatistician at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, conducted one such study in North Carolina, where many people rely on private wells with elevated levels of radon. Like radium, radon releases ionizing radiation as it decays, and Serre and his graduate student Kyle Messier found a correlation between radon levels in groundwater and rates of lung and stomach cancers. According to Serre, such findings suggest that radioactive groundwater could indeed pose a threat in the Middle East.

"They need to be concerned about how people consume this water," he said.

The Middle East may face even more pressure to use fossil aquifers in the future, with a rapidly increasing population and a climate that is projected to become even drier. Libya already relies on the Nubian aquifer for almost all its water needs, said Sturchio, and Jordan pumps 100 million cubic meters (about 26 billion gallons) of water per year from the Disi aquifer to its capital city of Amman.

But even if fossil aquifers are dangerously radioactive, the downsides of using them must be weighed against the alternatives. The WHO cautions that while its thresholds are established to protect public health, they "should not be interpreted as a limit above which drinking-water is unsafe for consumption," since the health risks of inadequate drinking water are likely to be worse than those of radiation.

Moreover, there are ways to use radioactive water safely, said Sherif. People can treat it to remove radium or blend it with water from other sources to reduce the concentration.

"There is a health risk from drinking the water if it's untreated," said Sturchio. "It's one thing that needs to be addressed before people use the water more widely."

Inside Science is an editorially-independent nonprofit print, electronic and video journalism news service owned and operated by the American Institute of Physics.