A look back at the Lehman Brothers collapse, and the global crisis that followed: Reporter's notebook

The collapse of the investment bank was a major factor in the global crash.

Looking up, it’s a peaceful morning on Monday, Sept. 15, 2008, but the mood in the air is tangible, heavy.

I’m anxiously waiting outside of Lehman Brothers’ headquarters in Midtown Manhattan getting ready to go live to report on the largest corporate bankruptcy in U.S. history. Just three years into my career as a journalist, I’m now covering what will likely be one of the biggest stories of my life.

I watch as workers solemnly shuffle out of the building, looks of exhaustion and disbelief on their faces. These now former Lehman employees carrying those paper filing boxes, each containing little trinkets and mementos of jobs now gone.

Employees tell me they’re angry with their company, with their country, that they never expected to be here, and now they have no idea what comes next.

A few are new hires, asked as recently as the previous Friday to report for work for business as usual.

Already the financial crisis has left a swath of destruction in its wake. Layoffs and foreclosures are rising. The stock market sinks deeper every day. You can feel the restlessness wherever you go: the grocery store, the gas station, the baseball game -- and especially Wall St.

There is an underlying panic lying in wait. It becomes the powder keg set alight by the match that is the Lehman bankruptcy. Brutal reality has set in, not just for Lehman employees but for workers around the country. There is tremendous uncertainty ahead for American companies and employees everywhere -- if Lehman can go down, anything can.

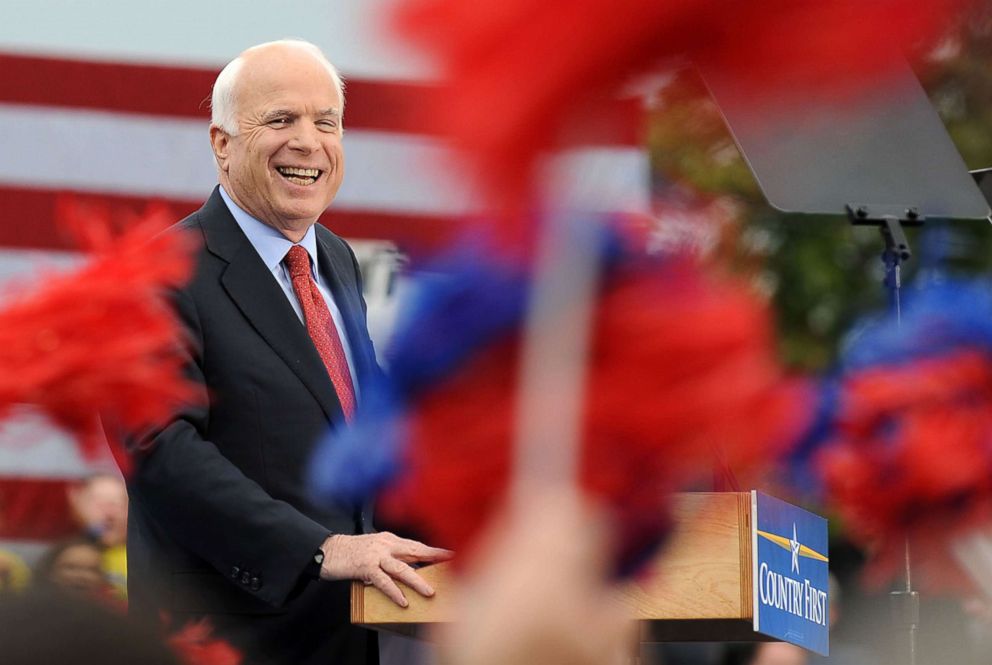

Days after Lehman’s fall, Republican presidential nominee Sen. John McCain would suspend his campaign because of the “historic crisis in our financial system,” suggesting Democratic nominee Sen. Barack Obama do the same until Congress could work out a plan about how to deal with the fallout in the financial industry.

To be sure, this -- the sudden collapse of a financial giant, a corporate staple -- was unthinkable just a few days before.

A week ago, Lehman Brothers was a 158-year-old institution with 25,000 employees. It survived two World Wars and the Great Depression. Yet on that morning, the market had spoken –- that history counts for nothing if you can’t pay your bills.

In an instant, billions of dollars in wealth was wiped out. Gone.

I look up, scanning the iconic Lehman Brothers headquarters and its thousands of windows –- across a few I can see a sign that reads: “F--- PAULSON,” as in Hank, the U.S. treasury secretary.

Over the weekend, there was lingering hope that Secretary Paulson -— along with the Federal Reserve, Bank of America and Barclays —- would work out a deal to save Lehman Brothers. But it turns out, to the surprise of many, there will be no white knight to step in.

Just a few months earlier, competitor Bear Stearns was spared through a sale to JP Morgan, albeit for the fire sale price of $2 a share -- a staggeringly low number everyone, including me, assumed was a typo when the news first hit the wire. In the subsequent years, many, including Paulson, will debate whether Lehman could have, or should have, been saved.

So here we are. For the better part of the last year, I have stood watch as a reporter as the crisis has escalated, from the faintly audible rumble of misgivings, to a panic, to a bloody stampede for the exits.

I’ve witnessed it outside of failing businesses, in unemployment lines, on shuttered factory floors, and inside the frenzied New York Stock Exchange. And now outside of what was one of the largest and most powerful financial institutions in the world -- Lehman Brothers is no more.

How did this happen? Greed? Too much risk-taking? The collapse of the housing market?

Everyone was left wondering: What about my retirement savings? My bank account? What about my job? My home?

There is a constant underlying drumbeat of fear. Another selloff. More foreclosures. When will this end? And how, many ask, will I make the next payment on my mortgage -- now bigger than the value of my home?

It’s all in the back of my mind as I ask myself: How did the smartest guys in the room get it so, so wrong?

Now, 10 years later, we can still debate what actually did bring Lehman Brothers and so many other companies to their knees. The answer is complicated, messy, and has vocal proponents on all sides.

There was the repeal of Glass-Steagall in the late 90s, which led to greater risk taking and looser standards at banks. There was the insatiable appetite among hedge funds and investors for more complex financial products tied to mortgages -– the dawn of mortgage backed securities, collateralized debt obligations and other complex derivatives.

Acronyms like MBS, CDO, and CLO were springing up all over Wall Street, on resumes, in conversations, yet few could fully explain them. There was the fact that anyone who wanted a mortgage -- or five! -- could get it, and many did.

The boom in “sub-prime,” thanks to hungry mortgage brokers and policies meant to push home ownership, encouraging many to spend money they didn’t have. And all of that money, all of that speculative capital pouring into home buying and mortgages essentially disappeared into thin air when the housing market collapsed -– causing chaos and devastation.

But whatever the underlying explanation, the reality is that a great many of those employees I saw that morning haven’t returned to the financial industry; their jobs have vanished along with their employers and -- in some cases -- entire industries.