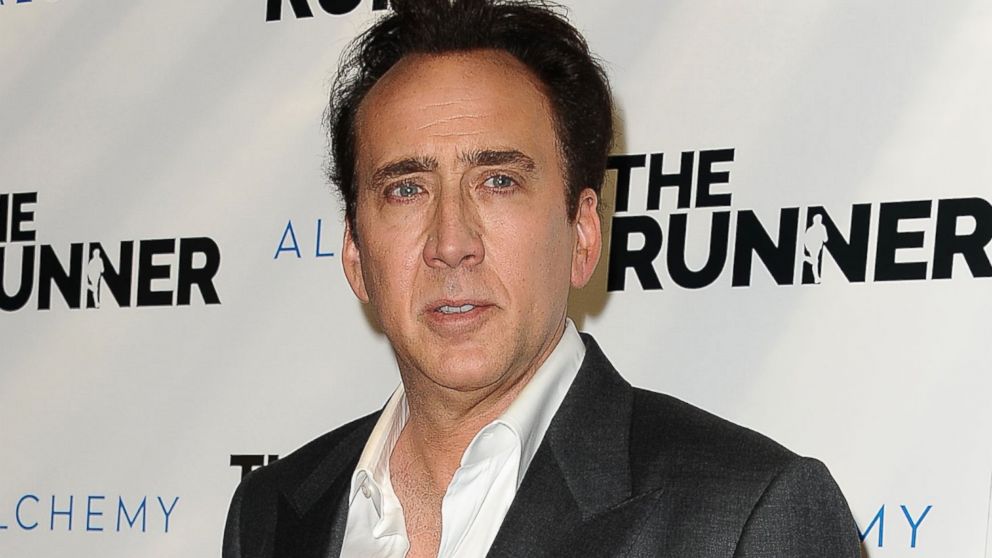

Dinosaur Skull Purchased by Nicolas Cage to Be Returned to Mongolia

The skull is to be returned to Mongolia.

— -- Actor Nicolas Cage has handed over an illegally imported dinosaur skull that he had purchased in 2007 to the U.S. government as part of an effort to return stolen fossils to Mongolia, Cage's representative said.

The Tyrannosaurus bataar skull was sold at auction in 2007 in Manhattan for $276,000 by Beverly Hills-based I.M. Chait Gallery, according to the U.S. Attorney’s civil forfeiture complaint.

Cage agreed to transfer possession of the fossil to the Department of Homeland Security, based on a determination that "the fossil was indeed illegally smuggled into the U.S. and rightfully belongs to the Government of Mongolia," Alex Schack, a representative for Cage, said in an email.

The skull is now in the possession of Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), a division of DHS that specializes in investigating stolen antiquities and cultural artifacts.

“Cultural artifacts such as this Bataar Skull represent a part of Mongolian national heritage. It belongs to the people of Mongolia," said ICE Acting Special Agent-in-Charge Glenn Sorge.

The civil complaint, which was announced last week, leaves the buyer unnamed. However, Schack confirmed to ABC News that Cage was the buyer and he was identified in 2013 when controversy over the skull arose.

At the time of sale, the skull was described as “an extremely rare tyrannosaurid” from the Late Cretaceous period (67 million years ago). The specimen measured 32 inches in length and was approximately 65 percent complete, with “knife-like serrated teeth,” according to I.M. Chait Gallery.

I.M. Chait did not respond to ABC News' requests for comment.

Cage received a certificate of authenticity from the auction company, according to Schack. In 2014, DHS contacted Cage’s representatives to inform him that it believed the fossil he had purchased may have been illegally smuggled into the U.S. from Mongolia.

He cooperated with the investigation and arranged for an inspection of the fossil by government officials, Schack said.

“I’m surprised Nick Cage didn’t challenge it,” David Herskowitz, a natural history consultant who organized the 2007 sale of the skull, told ABC News.

Herskowitz said that at the time of the sale, he believed the skull was properly imported. He also told ABC News that he found it “hard to believe” that the specimen was positively identified as being from Mongolia. He said multiple scientists reviewed the fossil eight years ago and identified it only as originating in “central Asia.”

While Herskowitz said he was surprised that Cage gave the skull to authorities, he said he understood the desire to do the right thing and cooperate with law enforcement.

The bataar skull was imported through an intermediary via Japan by self-described commercial paleontologist Eric Prokopi, who then put it up at auction at Chait in 2007, according to Prokopi's attorney Georges Lederman.

Prokopi pleaded guilty in 2012 to engaging in a scheme to illegally import numerous dinosaur fossils, including one count of conspiracy, one count of false statements on entry of goods and one count of interstate and foreign transportation of goods converted and taken by fraud, according to Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

As part of his plea agreement, Prokopi agreed to the forfeiture of a nearly complete Tyrannosaurus bataar skeleton (the First bataar), which sold at auction in 2010 for over $1 million, as well as a second nearly complete Tyrannosaurus bataar skeleton, a Saurolophus skeleton, and an Oviraptor skeleton, according to the Justice Department.

In July 2014, Prokopi was sentenced to three months in prison.

“Mongolian law at the time was very inconsistent and confusing at the time. It has since been changed," Lederman told ABC News.

Lederman said that when Prokopi put the fossil up for auction, he believed it to have been legally imported. Prokopi has since moved on and "is leading a law-abiding life," Lederman said.

Herskowitz said he believed Prokopi was in the business because he had a true passion for paleontology.

“Just because he was accused of something once, doesn't mean that everything he’s done was illegal,” said Herskowitz of Prokopi.