'A Killing on the Cape': The Murder of Christa Worthington -- Episode 2

The gruesome 2002 murder of Christa Worthington rocked a small Cape Cod town.

— -- An encore presentation of this "20/20" report will air on Friday, Dec. 28, 2018, at 9 p.m. ET on ABC.

This is Episode 2 of "A Killing on the Cape," a six-episode ABC Radio podcast and an ABC News "20/20" documentary. Watch the two-hour "20/20" documentary HERE

For Episode 1, please visit http://abcnews.com/akillingonthecape.

Subscribe and listen to the podcast on our partners and platforms: Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Play Music, TuneIn, Stitcher and under the "Listen" tab on the ABC News app.

Episode 2: The Shellfish Constable –

For the police department in the small Cape Cod town of Truro, Massachusetts, the gruesome 2002 murder of Christa Worthington was the highest profile case the department had seen in decades.

Worthington, a 46-year-old fashion writer and single mother, was found stabbed to death in her home on Depot Road on Jan. 6, 2002, with her 2-and-a-half-year-old daughter by her side, unharmed. Her garbage man, Christopher McCowen, 45, was eventually convicted of raping and murdering her, but his defense attorney claims he is innocent and is currently working on getting McCowen a new trial.

Prosecutors believe they have the right man behind bars, but at the time of the murder, the investigation into Worthington’s death led to a long list of potential suspects. Eventually, almost the entire town came under suspicion.

It was January, the dead of winter, when tourists have mostly vacated the quaint seaside town, which has a post office, a town hall, a grocery store, a few restaurants and small businesses, but not much else.

State police investigators took over the case from local authorities the night Worthington’s body was found. They began looking into everyone in Worthington’s life, even those who knew her when she worked as a fashion writer in New York City and Paris.

“She was glamorous in a certain way, even though everybody says Worthington would hate that word,” said Maria Flook, the author of “Invisible Eden: A Story of Love and Murder on Cape Cod,” a book about Worthington’s life and career before her murder. Flook said Worthington had been her student in a writing class she taught.

“She had that ‘glam’ factor, being somebody who worked in New York and Paris and was part of the fashion industry,” Flook added.

Worthington grew up south of Boston in Hingham, Massachusetts. Her father, Christopher Worthington, who went by “Toppy,” was a Harvard educated lawyer and Christa was an only child. Christa Worthington went to Vassar College at a time when the school, traditionally an all-women’s college, had just become co-ed.

Victoria Balfour, who was a Vassar classmate of Worthington’s from 1973 to 1977, said she was in an English thesis class with her. While they weren’t close friends, Balfour said she got to know Worthington since they were both English majors.

“Christa was someone you would know because she was so short, but interesting looking and pretty,” Balfour said. “You just knew who she was. She was one of those people.”

Balfour said Worthington wasn’t into fashion when they were at Vassar together.

“She was into [the] more hippie, peasant look,” she said. “No make-up. She would wear peasant blouses with long denim skirts to the ground and bandanas.”

Her most vivid memory of her, Balfour said, was seeing Worthington walking across campus with an arm load of books.

“She was brilliant in class,” Balfour said. “I know she graduated with honors… she was very bright in a kind of academic way, very thoughtful and insightful, and we would all look at her like, ‘wow.’”

After college, Worthington moved to Manhattan, where she began her writing career. She went on to write for the New York Times, Elle magazine, W magazine and Women’s Wear Daily. Worthington even worked as the temporary editor of Women’s Wear Daily in Paris for roughly two years.

"She loved Paris,” said author Peter Manso, who wrote a book about Worthington’s murder called, “Reasonable Doubt: The Fashion Writer, Cape Cod and the Trial of Chris McCowen,” and was a consultant for ABC News on this story. “She was known in Paris, she was known as a live wire, an American.”

Worthington eventually left Paris and returned to New York, where she continued her face-paced city life, mixing with those in the high-fashion industry.

Eli Gottlieb, a writer and novelist who worked with Worthington at Elle magazine in 1990 when they were editors there together, said at the time, the magazine was an “on-going party disguised as a publication.”

“And there was a lot of extracurricular fun,” he said. “Christa seemed to know a tremendous amount of celebrities. It wasn’t anything she was ostentatious about, but it was clear that she was really wired in, and she always used to have the latest gossip.”

But Gottlieb said Worthington took her writing “extremely seriously.”

“She sweated over her writing, she did not take it lightly,” he said. “And she turned out very elegant prose. It wasn’t always on weighty subjects, it wasn’t about world peace or global disarmament, it was usually about the latest desert boot or culottes trend, but it was well done… she was a talented writer.”

But as time went on, Gottlieb said Worthington seemed less fulfilled by writing and started to look for something more.

“After she left Elle magazine… she experimented for a while,” he said. “She was the antiques and collectibles columnist for the New York Times…and I think she had been doing this for 20 odd years and she was beginning to lose a little bit of interest, beginning to look for deeper fulfillment in life.”

For all her success, Gottlieb said Worthington’s personal life was filled with one tumultuous relationship after another, and she was “unable to happily settle down with anybody.” Over time, Gottlieb said Worthington’s relationships seemed to become shorter and more erratic.

“The people that she was with became stranger and weirder,” he said. “And every time the phone would ring and she would have some new story to tell, and it just went from weird to weirder.”

Worthington started to talk about wanting a child, Gottlieb said. At one point, Gottlieb said Worthington went so far as to write an article for Harper's Bazaar about it and even went on television to share it.

“I think it was called something like, ‘Do I Dare?’ and it was, ‘Am I selfish to try to have a child in-vitro at age 40?’” Gottlieb said. “The answer that came back from the audience of the television show she did, as I recall, was ‘Yes, you are.’ She was booed and hissed, and she didn’t really seem to mind.”

Gottlieb said Worthington seems a little shocked by the negative reaction she got from that, but said, “she thought it was all quite funny."

Looking for a change, Gottlieb said Worthington left New York in 1997 and moved to Cape Cod, where she had spent her summers as a child and where her family had a number of properties.

The first place she moved into was a small, almost shack-like, home that was owned by her grandmother. It was on Pamet Harbor, just down the road from her house at 50 Depot Road, where she would eventually move.

“In the Cape, Christa seemed to access the Truro version of herself, which was really more ‘let your hair down, walk around in flip flops and shorts, throw the Hermes… to the back of the closet,’” Gottlieb said. “She let herself unwind.”

Pamet Harbor is picturesque Cape Cod. The inlet is surrounded by beautiful sand dunes and Pamet marsh is where people go swimming, kayaking and paddle boarding. There’s a yacht and tennis club nearby.

Worthington’s shack was right next to the parking lot for the harbor, where every day pick-up trucks arrived with trailers carrying fishing boats.

According to Flook, Worthington would get upset that people would leave their boats in front of her house. But her complaints about it led to one of the most important relationships in her life.

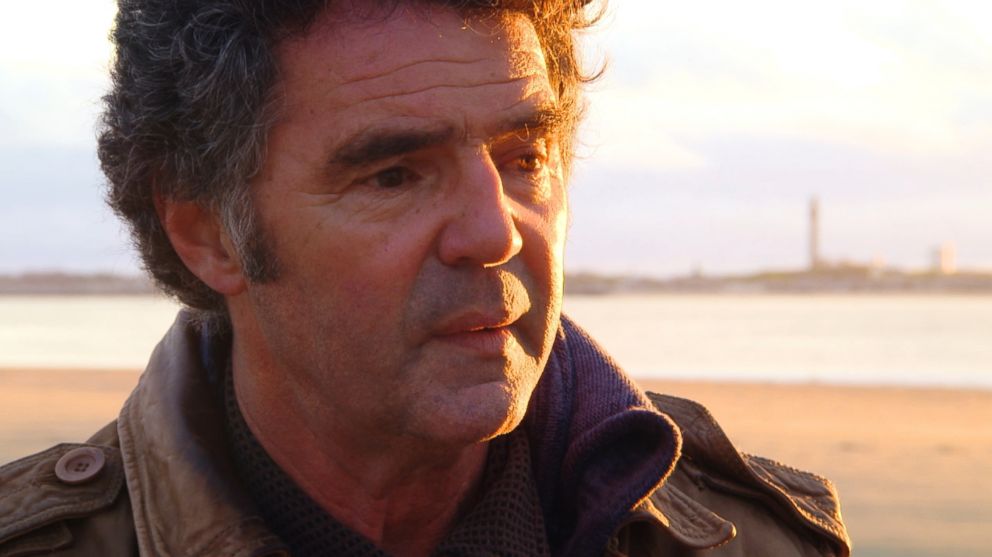

Flook said Worthington would go over and talk with the harbor master, Warren Roderick, to complain about the boats in her yard. While talking with Roderick one day, she met Tony Jackett.

“She noticed him because he was very handsome,” Flook said. “He has black curly hair and a beautiful, golden complexion. He’s very, very appealing when you first meet him because he’s wide open and friendly.”

And he noticed her too. Flook said within a few weeks the two took a liking to each other.

Jackett was the shellfish constable of Provincetown and Truro. It was his job to enforce fishing laws and make sure fishermen had the proper licenses. He also used to rollerblade in the parking lot next to Worthington’s home.

“Before you know it, he was going over to her house for tea and then of course, it became a little deeper,” Flook said.

The one problem was that Jackett was married to his wife Susan and they had six kids together.

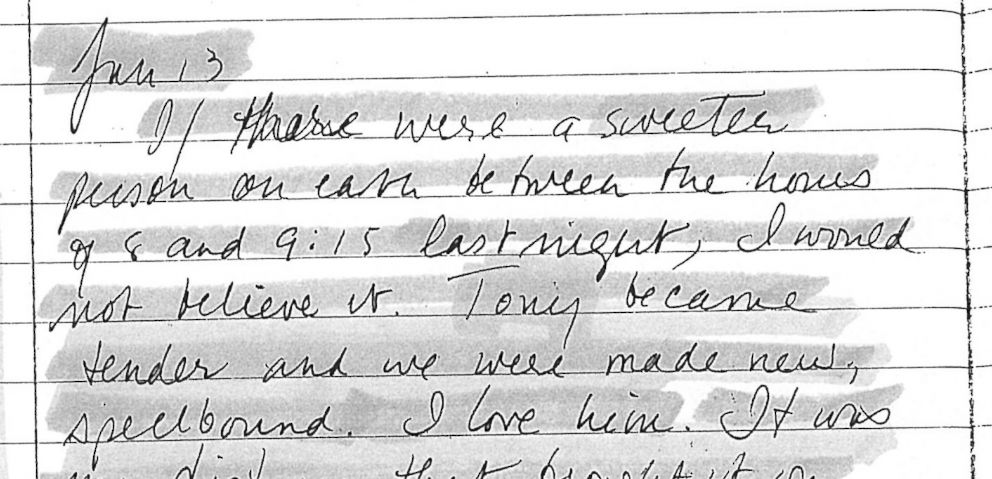

Worthington wrote about Jackett in her diary, describing him as “tanned to a burnt amber color.” She also wrote about how she became swept up in an affair with him.

“If there was a sweeter person on Earth between the hours of 8 and 9:15, I would not believe it… Tony became tender and we were made new spellbound. I love him,” she wrote in one entry.

At another point, Worthington even wrote about how ordering pizza in public was a thrill. “That is adultery,” she wrote. “When ordering pizza became a thing of beauty.”

Their affair lasted more than two years without Jackett’s wife or his kids finding out.

Today, Jackett is 67 years old and lives in Wellfleet, another small town on the Cape just south of Truro. He still lives with his wife, Susan.

The way Jackett explained his affair with Worthington was very much a “one thing led to another” story. He told ABC News he first met her that summer in 1997.

“I think there was a time that she asked me to help her or do something up at the house,” he said. “That was when I got to be more friendly with her.”

“It seems to me, that I went over to her house and was having a cup of tea, and then the next thing you know, you’re in bed,” Jackett continued.

But Jackett said he didn’t really see Worthington very often.

“It’s a small town,” he said. “You’re nervous, or at least aware, that you could be seen.”

But the affair went on. At that time in his life, Jackett said, he wasn’t going through a mid-life crisis, per se, but he said he was “more curious about an opportunity to explore and do different things.”

“I had no plan on leaving home,” Jackett continued. “I certainly wasn’t going to leave one family and go start another.”

When they got together, Jackett insisted that Worthington told him that she couldn’t have children. She was in her early 40s by then, and he said she had told him doctors said children weren’t possible for her. But to his shock, Worthington got pregnant.

“She tells me, ‘I think you should sit down. I have something to tell you and I’m pregnant,’” Jackett said. “So I’m thinking, ‘How could I be so dumb?’”

Jackett said he asked Worthington what she wanted to do because he said he told her he wasn’t going to leave his wife and six children to start another family. He said Worthington told him not to say anything, that it was early in the pregnancy and she might lose the child, and that she was going to leave town to help take care of her ailing mother.

“I didn’t know if that was something I could keep from my wife for very long,” Jackett said. “I did manage to do that for a couple of years. I was shocked, because she had convinced me that she couldn’t have children.”

After Worthington became pregnant, their affair ended, but their secret continued.

Around this time, Worthington moved from the house on Pamet Harbor to the house on 50 Depot Road, where her daughter Ava was born in May 1999. It was nearly two years after her birth that Jackett said he finally came clean to his wife, Susan.

At some point in the spring of 2001, about eight months before Worthington was murdered, Jackett said Worthington had started asking him to include Ava in his life and medical insurance, as well as provide child support. Jackett later told police that Worthington had been “nagging” him for child support.

She even got a lawyer involved, who was threatening to garnish his wages to help provide support for Ava and asked him to sign a formal agreement.

Jackett said the agreement was set up in a way that he would still be able to keep the child and the affair a secret from his wife, but he said he felt pressured to agree to it or Worthington would expose the affair.

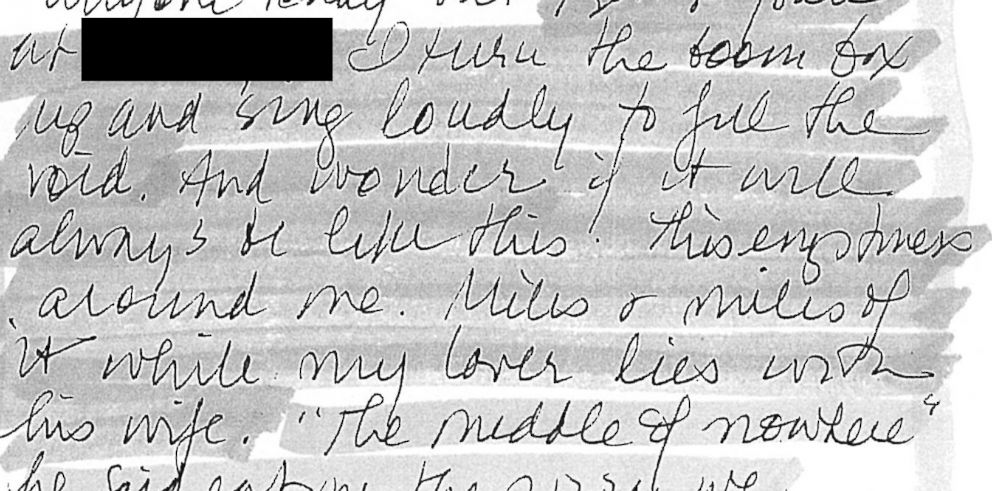

Her diary entries showed that she was growing frustrated with Jackett and at times she seemed outright angry at him.

“I turn the boom box up and sing loudly to fill the void, and wonder if it will always be like this,” she wrote. “The emptiness around me, miles and miles of it, while my lover lies with his wife.”

Despite her frustration, Worthington was not the one to expose their affair. Jackett did. He told his wife after he said he couldn't live with the secret anymore, nor could he live with he told police -- that was the "power" Worthington had over him. So he decided to come clean.

“When I told her [Susan] the news … she was in a state of shock,” Tony Jackett said. “She said, ‘OK, what I want you to do is, you’re going to go down the hall and stay in that bedroom until I figure out what to do with you.’ And I remember thinking, ‘Alright, OK, so I go that out of the way.’ I never left. I was never kicked out of the house.”

Jackett said he and Susan started to talk after that and agreed to see a therapist. According to a report from Massachusetts State Trooper Christopher Mason, who was investigating Worthington’s death, Jackett told him that after he came clean about the affair and the child, Worthington gave him plenty of time to get his family together, and after he added Ava to his health insurance, she stopped pursing him with a lawyer.

With everything out in the open, Jackett said Worthington seemed less concerned about how and what she would eventually tell Ava about who her father was. Eventually, Jackett’s wife Susan decided to make Ava and Worthington part of their family and all of them went on to regularly eat dinner together.

“It wasn’t difficult once I got to know Christa,” Susan Jackett told ABC News. “I liked her. I enjoyed her company, and I just felt sorry for her dilemma, for Ava’s dilemma, my dilemma, my children’s dilemma and… if Tony and I are going to stay together, we have to make this work.”

The Jacketts said they and Worthington were involved in each other lives and they were getting along, but her death quickly made them targets for suspicion.

On Jan. 6, 2002, after Worthington’s ex-boyfriend Tim Arnold had found her beaten and stabbed to death in her home and he had taken Ava over to Worthington’s uncle’s house, the Jacketts were told to come over.

“I didn’t know that she was dead when they called Tony to come pick Ava up,” Susan Jackett said. “[Tony] He said, ‘come on, we’re going to go pick up Ava, and something’s happened to Christa,’ that’s how he worded it.”

Susan Jackett said she and Tony got in the car and drove over to John Worthington’s house.

“I said [to Tony], ‘Is Christa in the hospital? Did she fall? Is she OK? How long will we have Ava? And he said, ‘Susan, she’s dead,’” she said. “I just couldn’t believe it. I was in shock.”

Just two weeks prior, Tony Jackett said he, his wife Susan and Christa Worthington had all been together at a party, but then he said, "my feeling so lucky turned upside down."

“I don’t think I was aware of me being a suspect initially,” he said.

At John Worthington’s house, Trooper Mason interviewed Tony Jackett. He asked him where Jackett had been that day, and in his report, he wrote that Jackett said he had been in Pamet Harbor in the morning and then later had gone to Provincetown, where his son Luke had been shellfishing with a friend. Jackett told Mason that he then went to his father-in-law’s to watch a Patriots’ game, and then left to go home and eat dinner. Then Jackett said he received a call from Worthington’s friend Francie Randolph, telling him Worthington was dead.

Mason also asked Jackett where he was the two days prior to her body being found. Since Worthington’s body was already stiff when paramedics arrived, investigators believe she had been dead for some time. Mason’s report noted that on the Friday before – Worthington died on a Sunday – Jackett told the trooper he and Susan had gone see “The Royal Tenenbaums” at Cape Cod Mall cinemas in Hyannis, Massachusetts, and then on Saturday, they had gone to see “A Beautiful Mind” at Wellfleet cinemas, both outside of Truro.

Mason later checked with the theaters and wrote in his report that there were showtimes for when Jackett said he and his wife were at the movies.

“We had people that we knew, that we saw in the movie theater, so we could account for our time,” Tony Jackett said. “But even though they [police] didn’t, or was reluctant to rule me out, they would say, ‘We can’t rule him in, we can’t rule him out. It was going to stay like that until they made an arrest.”

It was another three years before police would arrest someone else in the Worthington case. During that time, the Jacketts said they endured sideways looks from some in the community who thought they might be involved in Worthington’s murder.

“You just can’t believe that they would suspect you,” Susan Jackett said. “We were questioned quite a few times.”

One of the people who became suspicious of the Jacketts almost immediately was EMT George Malloy, who was on the scene at Worthington’s house the night her body was discovered and who brought Ava over to John Worthington’s.

While they were all at John’s house, Malloy said Susan Jackett made what he called “offensive” comments about Ava, which made him suspect the Jacketts were involved in Worthington’s death.

“[She] said to me, ‘Don’t listen… to anything this little girl has to say, she’s a … liar,’” Malloy said. “And I’m thinking, ‘What the ----?’ … I just found that to be extremely offensive, when you’re talking about a 2-year-old, calling a 2-year-old a liar.”

The Jacketts have both always denied any involvement with Worthington’s murder. When asked about Malloy’s claims of what she said that night, Susan said when she arrived at John Worthington’s house, she said Malloy was sitting on the floor with the little girl.

"I felt like I couldn't get near her and I was afraid she would reject me, being how she was-- that she's with who's she with," Susan Jackett said. "So I just stood there and I was kind of chatty and I said, you know, 'I came to pick up Ava,' and, 'Would you like to have a bath Ava?' I said, 'Once in a while, she'll tell me that she didn't like to take baths and her mother said she actually loves baths, but sometimes she tells fibs."

"I was just trying to make light conversation," she continued. "And that somehow or other, I don’t know how that got twisted around that I said she was a liar, or not listen to her what she said. I was just trying to make conversation. How-- she’s little and she really loves baths, but she’ll say she doesn’t like them… but that was so untrue that I said that child was a liar. She was a baby. She didn’t even know how to tell lies.”

Trooper Mason, as well as Sgt. William Burke, who aided the investigation, interviewed nearly every member of the Jackett family, as well as dozens of others close to them and Worthington, and knew about the friction between Tony Jackett and Christa Worthington before he came clean about their affair to his wife. Others backed up that the relationship between the Jacketts and Worthington had been good at the time of her death.

In the months after the murder, police questioned the Jacketts several times and asked both of them to take polygraph tests, during which they were asked questions, such as, “Did you stab Christa?” and “Do you know who stabbed Christa.” In both of their tests, the state trooper who administered them wrote that, in his opinion, there was no deception found.

Mason and Burke’s focus on the Jacketts seemed to ease in the months following the murder. In looking at Mason’s interview reports, each subsequent interview with them was shorter. For example, in his first interview with Tony Jackett, Mason’s report was seven pages long. The second time, his report was three pages and by the last interview, which occurred on May 22, 2002, a little less than four months after Worthington’s murder, the interview summary was just two pages.

But the police suspicion that surrounded them, particularly around Tony, continued to affect them directly, the Jacketts said.

After Worthington’s death, they fought to get custody of Ava and ended up going to court over it. The media caught wind of the case and suddenly the Jacketts found themselves at the center of a camera-flashing whirlwind as they ascended the courthouse steps.

“I went to court mostly because my wife told me, ‘Tony, if you don’t try and win custody of Ava, I’m going to question why I stayed with you… that girl deserves to have a father just like your other children,’” Tony Jackett said. “I kind of thought like I was being thrown to the wolves a little bit.”

Media had turned out from everywhere, Jackett said. As he was fighting for custody, he said the district attorney showed up at his hearing and told the judge that he couldn’t rule Tony Jackett in or out as a suspect in Worthington’s murder.

“So I think the judge felt the safe thing to do was to award temporary custody, and a lot of times, the one that gets temporary custody most often ends up with permanent custody,” Tony Jackett said.

It was Worthington’s good friend Amyra Chase who was awarded custody of Ava, and the little girl went on to live with her in Boston. Worthington had apparently named Chase as the person she wanted Ava to be with in case something happened to her, but the Jacketts believe the cloud of suspicion over them hurt their chances.

But with the police unwilling to officially rule anyone out as a suspect, the Jacketts said they faced intense scrutiny until an arrest was finally made and someone else was charged with Worthington's murder.

“I was never called or told that I was not a suspect,” Jackett said. “I did get a letter from the D.A., I think it was phrase as ‘diminished.’”

Aside from the Jacketts, police expanded their investigation to looking into Worthington’s social circle and even her father.

“It was shocking when people learned, after Christa’s murder, that he [her father] was involved with a heroin addict rent girl,” Maria Flook said. “Christa knew about this prior to her murder and was quite worried.”

Eventually, police expended their search for Worthington’s killer to the entire town of Truro – asking every man in town to volunteer to submit a DNA sample and planting suspicion from neighbor to neighbor.

“It was such a nationally publicized case,” Flook said. “This was not just a little Cape Cod murder. It suddenly involved New York, Los Angeles, the whole country was watching what was happing with this murder.”

This article is part of an investigative series by "20/20" and ABC Radio looking into the murder of Christa Worthington and the trial and conviction of Christopher McCowen. Watch the two-hour "20/20" documentary, "A Killing on the Cape," HERE and the six-part podcast can be heard on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Play Music, TuneIn, Stitcher and under the "Listen" tab on the ABC News app.