How a dad overcame anxiety about bringing son with autism to work today

A dad shares son's autism diagnosis and how his family has changed.

James Okungu is a journalist at ABC News.

I wasn’t going to bring my child to work.

That’s the conclusion I reached once I finished reading the email invitation from the company’s president about “Bring Your Kids To Work Day.”

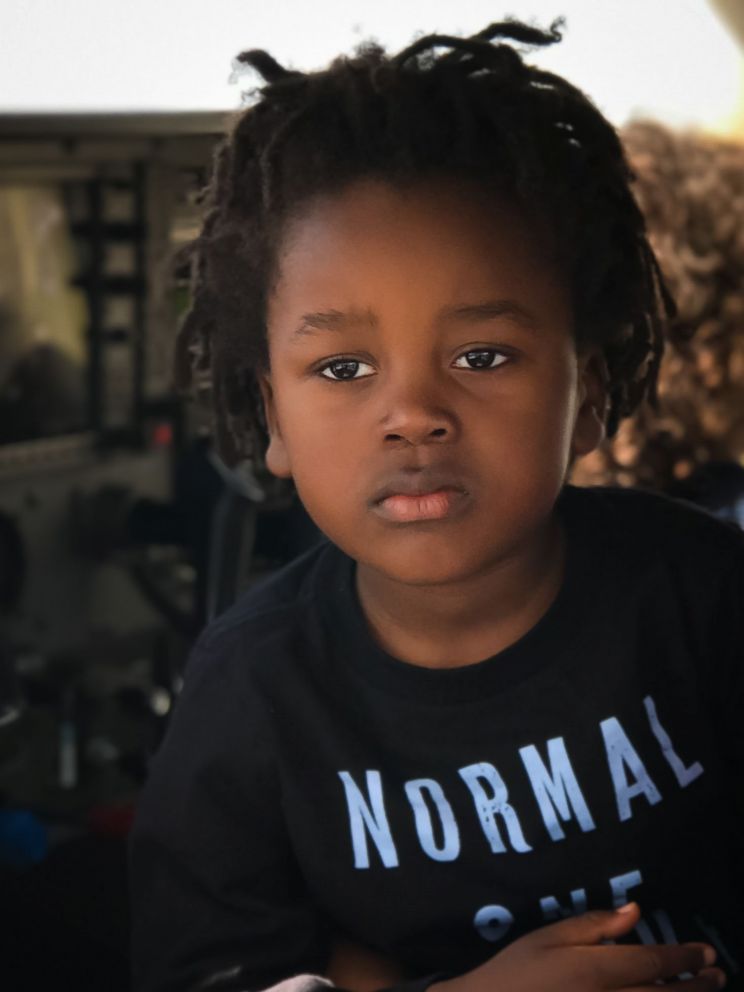

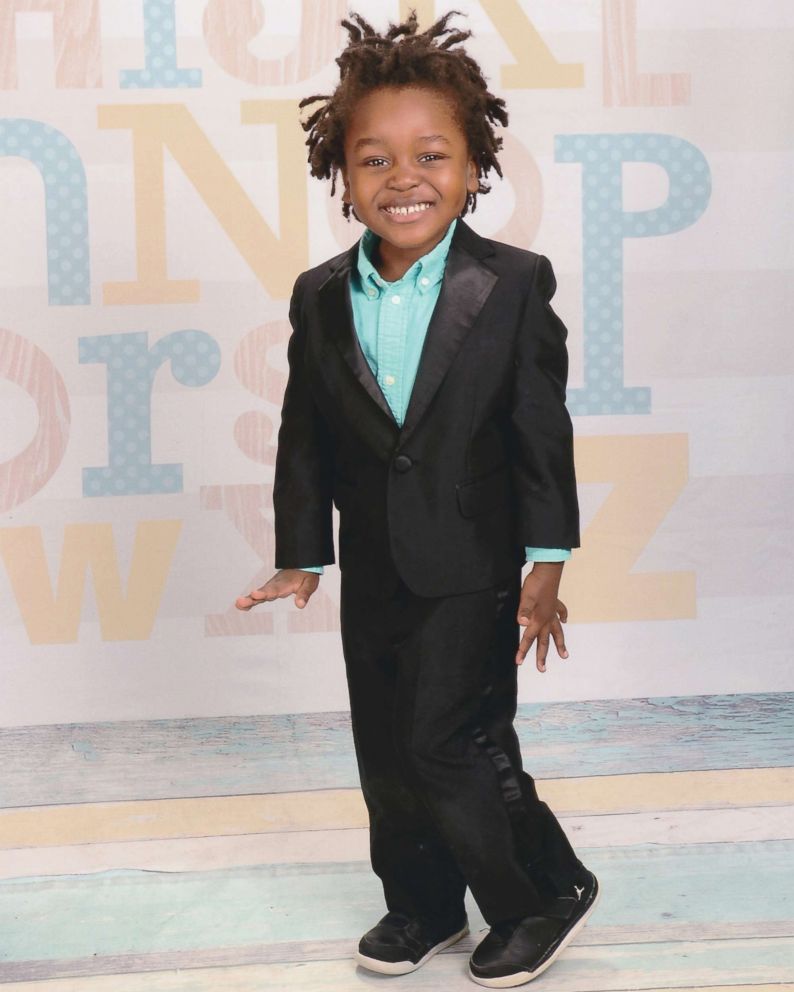

It’s not because I’m embarrassed by Jayden, nor is it because he is not cute. In fact, some of his most striking features are his big wide smile, the innocence in his eyes and his infectious laughter.

It’s because he has autism.

Autism is a learning disorder that affects people in different ways. For Jayden, it means he has difficulty in acquiring everyday skills that come naturally to other children, such as correctly interacting with toys and pointing to objects they want. At almost 5 years old, he is almost non-verbal, with just about four words in his vocabulary -- "eat," "more," "hi" and "bye."

Jayden’s diagnosis was painful and very difficult to handle. However, by understanding his disorder we now feel more equipped to help him and look forward to the future. We have learned how to appreciate life’s little victories and be grateful, to be more patient with each other and never take each other for granted.

The beginning

“Has anybody mentioned the a-word?” she asked. I searched my mind trying to figure out what she was alluding to. “A-word?” I muttered. “Yes, autism,” she said.

This was the conversation that began my family’s journey with autism. The lady was a special instruction teacher who had begun seeing Jayden at about the age of 2, after a recommendation by his pediatrician. His doctor had become concerned because, at 9 months old, Jayden had not said the two precious words that parents long to hear from their young children -- "mama" and "papa."

We arranged a psychological evaluation through a service coordinator we had been paired with after calling 311, the New York City help line. A psychologist came to our apartment bearing a huge bag containing all manner of toys; shiny, reflective toys, colorful balls, playing blocks. It looked like it could be a child’s dream play set, but not for Jayden. He barely showed any enthusiasm for these toys.

After about half an hour with Jayden, observing and interacting with him, trying to get him to play with the toys, he delivered his conclusion.

“I am diagnosing Jayden with Autism Spectrum Disorder,” he said, and then proceeded to explain what the next steps would be. I remember him standing there and watching his mouth move. If I said I recalled what he was saying, I would be lying. I was having an out-of-body experience, trying to fathom the news that had just been delivered to us.

Our minds went on a quest for answers. Why was this happening to our son? What did we do wrong? Would he be OK? Was therapy going to give us that glimpse of hope that we so yearned for?

Early Intervention

The autism diagnosis qualified him for services under a program known as Early Intervention -- a free program that offers children with development disabilities support to help them overcome delays in their progress. In New York State, it is offered until the age of 3.

Other evaluations determined that he needed both physical and occupational therapy. The physical therapy would help him walk better, stopping him from wobbling and falling so often. The latter would train him in fine and gross motor skills.

Once Jayden began receiving therapy, our apartment became a revolving door of therapists, one leaving just as the other arrived. He was receiving twenty hours of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) therapy and four hours of speech therapy per week. He also received four hours each of physical and occupational therapy, as we fought the clock to get these services before he aged out of the program at 3 years old.

Adjusting our lives to accommodate his therapy was very challenging. I worked overnights, my wife worked mid-morning until 7 p.m. Our schedules meant juggling a few hours of sleep in between Jayden’s therapy and work.

But we learned a lot from the six therapists working with him every week during the year of early intervention. We could now understand the signs we hadn’t, such as Jayden’s tendency to walk on his toes, his fixation with spinning the wheels of his toy cars, running back and forth across the living room, his hand-flapping and his discomfort with loud noises.

Coping

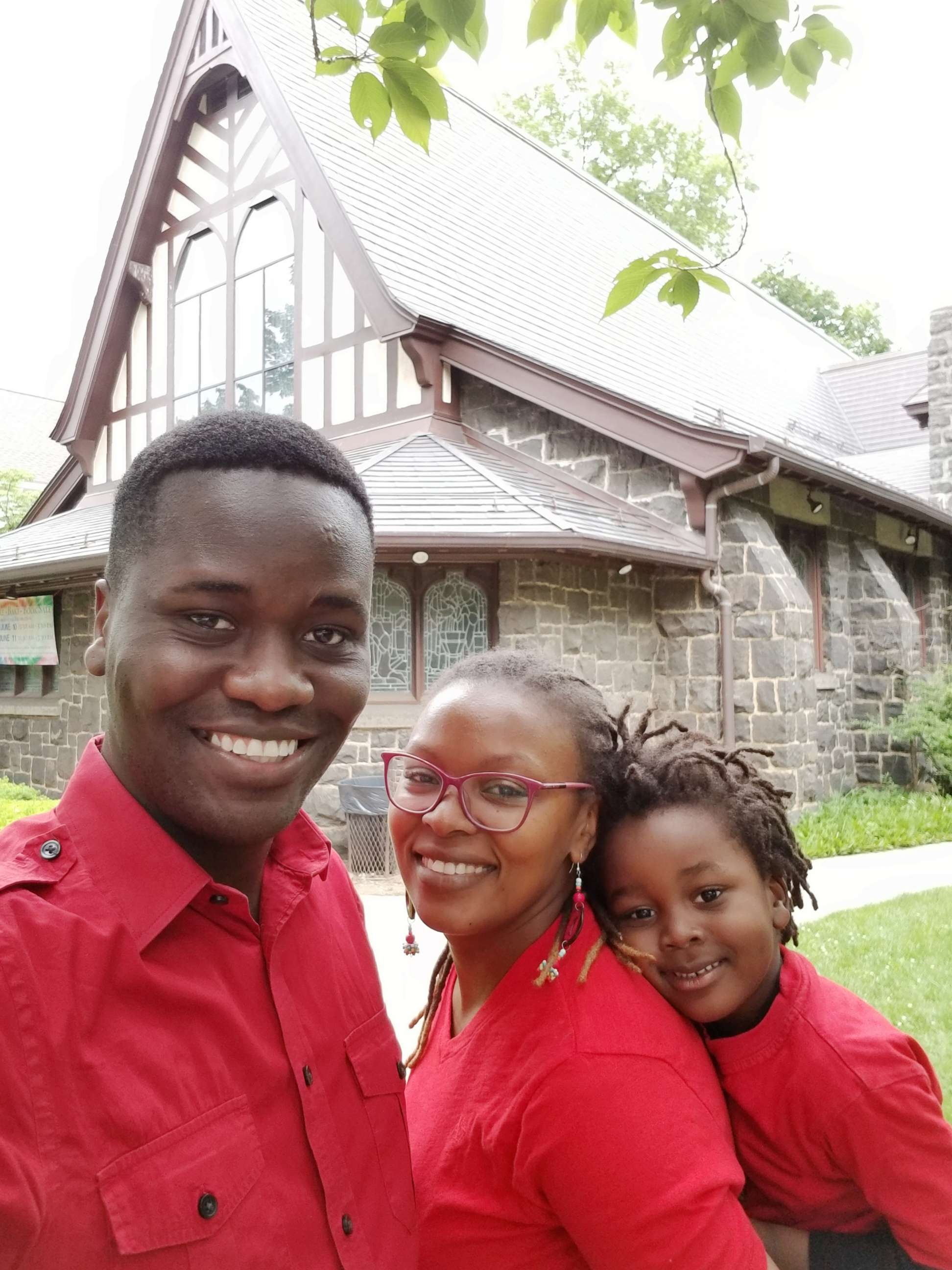

After Jayden’s diagnosis, my wife, who had been a high school teacher back in Kenya, started a master’s degree in education. She wanted to learn more about special needs kids and be better suited to help Jayden.

Shuffling between meetings with therapists and teachers and training sessions on autism and work, my wife and I almost lost each other. Our marriage suffered. We would both be so exhausted at the end of the day that intimacy became something of an afterthought; there was no room left on the schedule.

It certainly didn’t happen overnight, but the exhaustion built up, juggling work and household chores while constantly reminding Jayden to stop dangerous behaviors like jumping from the couch to the floor.

One of the most frustrating things about his condition is that nobody knows what lies in the future for him. There is absolutely no yardstick that can be used to predict if he will develop speech or how independent he will be in the future. It’s all in limbo.

Anxiety over Jayden’s wellbeing and living so far from the support of relatives led us to realize we needed a better coping mechanism.

New approach

Jayden has been attending a pre-school program in a special needs school. He goes to Kindergarten in the fall. In his time there, he has made progress -- not huge strides, but small steps in the right direction. We have come to learn to cheer these small steps and celebrate them as though they are greatest achievements. We broke out in dance once Jayden mastered toilet training, embraced and kissed him really hard when he learned how to put on his own shoes and we were beyond ecstatic when he gained interest in the books and toys he had previously ignored.

We have developed a reward system that has helped us work on his patience. We offer him rewards such as candy and potato chips when he sits nicely at the table when we are eating out in restaurants, or extra play time with his iPod and phone when he cleans up his toys or feeds himself.

By learning to understand the unique qualities of our son, we have been able to find ways to help him succeed. Once we discovered his love for water, we let him take extended bubble baths, enrolled him in a special needs swimming program and planned more trips to the beach and indoor water parks. When we learned that he loves posing for photos, we began play modelling sessions.

We have learned to take things slowly and be more patient with him. Stopping to explain to him why we can’t get on a certain train, stopping to explain to him why we have to leave the park at dusk, trying to preempt anxiety-causing situations and helping him navigate the stress associated with such events.

Josephine has picked up kickboxing while I have stepped up my workout routines. We have also learned the importance of carving out some personal time to relax, breathe and appreciate each other.

Looking toward the future

I knew nothing about autism when my son received his diagnosis. I was familiar with the word from the ubiquitous donation boxes at storefronts labeled “Support Autism Awareness.” I knew it was some sort of illness that affected children. That was it. Things are different now.

Reading about the police-involved shooting of a young father with mental health issues in Brooklyn and the murder of a 5-year-old non-verbal child with autism, allegedly by his father, in Tennessee, stirred up very strong feelings. Could these tragedies have been avoided with more knowledge on mental health and autism-spectrum disorders?

How equipped is law enforcement in handling cases involving people on the spectrum? Could Jayden’s ticks -- his hand flapping, his almost involuntary jumping, his screaming, his lack of skill in following instruction, his lack of speech -- one day be misconstrued as non-compliance with direction from law enforcement or considered a sign of aggression?

Jayden is an adorable child. His smile has the ability to melt the heart of even the toughest of men. Whenever he hugs me, he squeezes really tight while gently patting my back at the same time. In those moments, I feel as though he, in his own way, is reassuring me that everything will be OK.

Jayden is coming to work with me after all, because just like other kids he deserves all the love and opportunities he can get.