The Only Two Living US Mass School Shooters Who Are Not Incarcerated

Two boys killed five people at their middle school and now they are free.

— -- Adam Lanza killed himself. So did Seung-Hui Cho at Virginia Tech. And so did Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold in Columbine. And Christopher Harper-Mercer in Roseburg. And Elliot Rodger in Isla Vista.

If you go down the list of mass shootings at U.S. schools, most of the killers turned the guns on themselves after killing classmates and teachers. Several others were killed by police, and a few were taken into custody alive.

But only two are now out of prison, one of whom was arrested with a gun after his release, while the other has since applied for a concealed carry permit.

Not only that, but because Mitchell Johnson and Andrew Golden were minors at the time of the 1998 shooting – 13 and 11, respectively – when they killed five people in what was then the second-deadliest U.S. school shooting, Arkansas state law mandated that they be released on their 21st birthdays, with their records sealed.

Little has been reported about the lives of Golden and Johnson since they were released in the mid-2000s, but they seem to have one thing in common: neither apparently swore off guns after their time in juvenile detention.

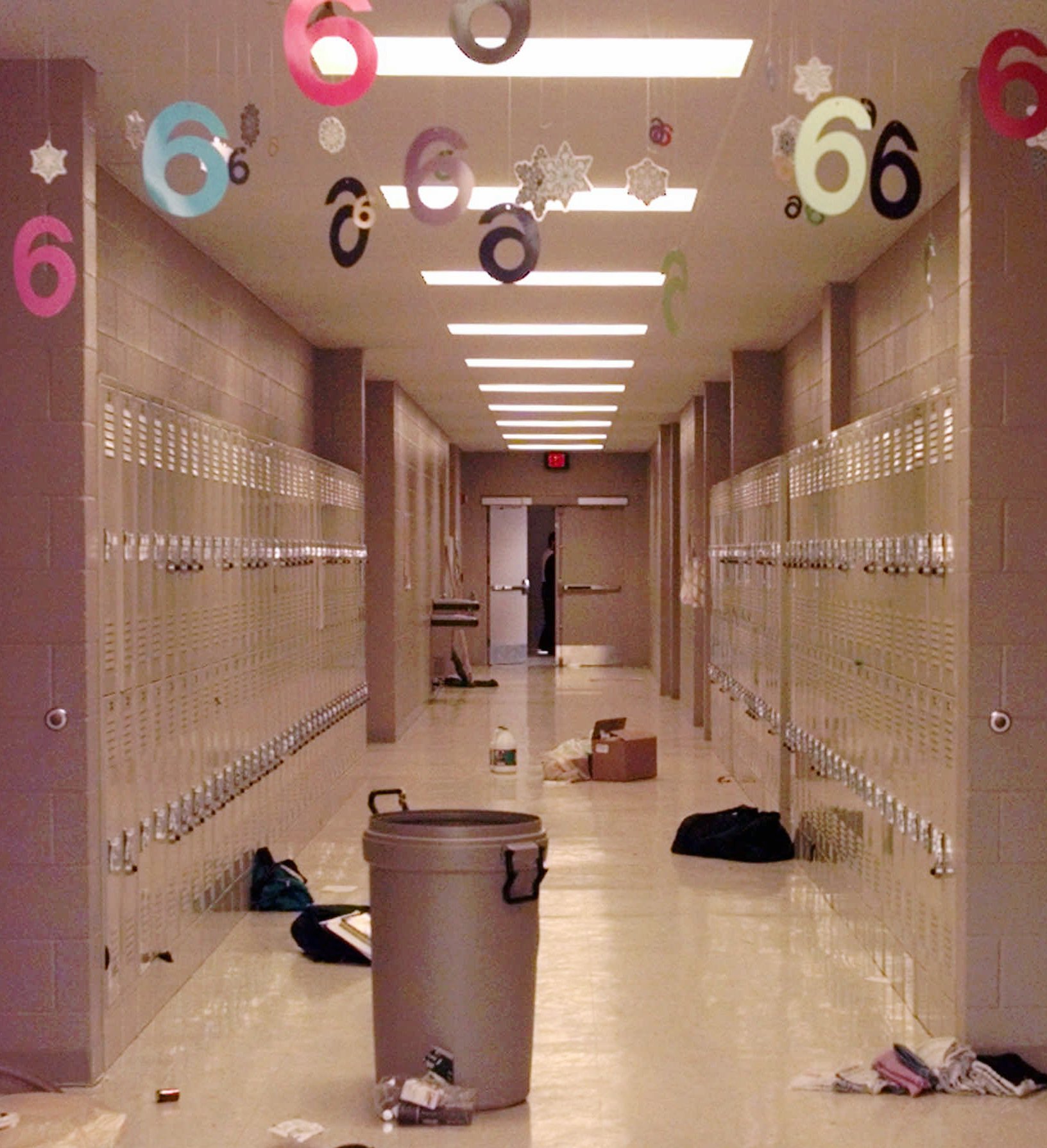

THE DAY TWO BOYS BECAME MASS SHOOTERS

Debbie Spencer was a science teacher at Westside Middle School in Jonesboro, Arkansas, in 1998 and taught both Golden and Johnson. She said Johnson "was one of the most polite students I've ever had. Always 'Yes, ma'am, no ma'am,'" she told ABC.

On the other hand, she said, Golden was "sneaky."

"He would do enough to get by. I remember the conversation we had the day before [the shooting]. I was going over to see if they wanted to know what their grades were so far," Spencer said, remembering that Golden had just barely gotten a B.

"You just got by by the skin of your teeth, didn't you?" she recalled saying to him.

"And he said, 'Yup, I always do,'" she said.

"It gives me chills because he knew what he was going to do at this point," she said.

The two were reportedly planning a shooting and getaway, with news reports at the time detailing how Johnson took his parents' car and the boys broke into Golden's grandparents' home where his grandfather kept his guns unlocked. One of the pair then pulled the fire alarm at lunch and opened fire when people started to flee.

"They were hiding in bushes and shooting at us," Spencer said. "We didn't know what was going on. It was an ambush. It was chaos.

"I didn't even know it was that close to me until I was giving the police my statement and I saw, 'Oh look, there's a hole in my purse,'" she said.

Jonesboro was tied for the second-deadliest school shooting in U.S. history at the time, according to an ABC News analysis of FBI records.

Part of the reason it is not as well remembered today stems from a matter of timing, one expert says. Golden and Johnson didn't know it when they pulled their respective triggers, but little over a year later, a pair of teenage boys was going to open fire at their Colorado school in a horrific, deadly event that unfolded on live TV.

Journalist Dave Cullen spent nearly 10 years writing a book about that shooting at Columbine High School, and said the Jonesboro shooting and others contributed to Columbine's resonance.

"There had been the lead up to [Columbine] and the growing anxiety in the country about these school shootings," Cullen told ABC News. "If you had had Columbine out of the blue, it would have been horrifying but it would have seemed unique... it would seem more like a one off. The fact that it felt like part of a pattern is what made it much worse -- a pattern but taken to an extreme, way beyond our imagination."

In the subsequent 18 years after Jonesboro, the Westside Middle School shooting was knocked down from being tied for second to being locked in a five-way tie for ninth deadliest shooting in the nation, the ABC News analysis concludes.

Golden and Johnson are the only two U.S. mass school shooters from the past century who are alive and not incarcerated.

THE JUSTICE OF JUVENILES

In most mass killings, which the FBI defines as any incident in which three or more people are killed, the offenders put on trial are convicted of at least one charge of felony murder. Felons are barred from possessing firearms.

But in the case of the Westside Middle School shooters, they were tried as juveniles, which means they were technically found "delinquent" instead of "guilty," and even though they served time, they came out with sealed records.

Back on March 24, 1998, the pair got guns from Golden's grandfather's house, went to school, pulled the fire alarm after lunch and stood outside the door where they knew students would be fleeing. They opened fire, killing four students and a teacher, and injuring 10 others.

Less than 10 years later, both men were free.

The decision to charge the pair as juveniles was not really a decision at all, but the only option: At the time, Arkansas did not allow juveniles to be tried as adults. That law was changed a year after this case, the Arkansas Bureau of Legislative Research said.

Many specifics of their story after they were sentenced are hard to pin down because of state laws that protect both juvenile offenders and gun owners, or would-be owners. In Arkansas, the majority of juvenile cases are sealed, a Craighead County Court official told ABC News, so both court officials and lawyers involved with the cases are not only barred from revealing the details of the case but also from acknowledging the existence – or non-existence – of those cases in the first place.

According to John Smith, the chief deputy clerk for the Craighead County Circuit Court, there is a good chance Golden and Johnson's court records had been destroyed, and after a week of searching, he could not find the physical copies.

GUN POSSESSION AND FREEDOM

Arkansas also has a law that prevents anyone in the state police department from confirming the status of any conceal carry permit application, or the names of individuals who have or have not applied or were rejected. The law is relatively new, coming into effect in 2009, the Bureau of Legislative Research confirmed.

Before the law changed, however, Arkansas State Police spokesman Bill Sadler had confirmed to The Arkansas Times, based on the fingerprint needed to apply, that Golden had applied for the conceal carry permit in 2008 using the name Drew Douglas Grant. When ABC News asked last week, Sadler declined to comment because of the new law, but he did explain that sealed records show up in law enforcement background checks though not civilian ones like employer background checks.

According to The Arkansas Times' account, when Drew Douglas Grant applied for a concealed handgun carry license, he listed an address in Arkansas, about 70 miles northwest of Jonesboro. The paper reported that his application was denied because at least one answer – his address history – was proved false after not listing the juvenile detention facility or subsequent federal detention facility where he had lived for several years.

Even though he could only speak in hypotheticals, given the legal restrictions, Sadler said he was not surprised that Golden, by any name, would be rejected.

"When you commit a crime such as the one that was committed at Westside Middle School, and even if you change your name from what your name was at the time of the crime, you can't escape what the clerks knew," Sadler said of the clerks tasked with approving or denying conceal carry permits.

"Anybody who's changed their name, you can't change your fingerprints," he said.

Sadler said state law does not require an individual to register the specific handgun the applicant intends to conceal, and gun ownership is technically not a requirement for applicants. As a result, there is no way of checking whether Golden owned a gun. Sadler did not respond to the question of why someone would apply for a concealed carry license without owning or having ready access to a gun.

As for Johnson, he obtained a firearm at some point after his release. After a traffic stop in Arkansas in 2007, he was arrested for possessing a firearm in the presence of a controlled substance. The lawyer who represented him in that case, Jack Schisler, told ABC News that in more than 20 years of practicing law, he has never seen that charge used. When asked why that particular charge was used, Schisler said: "Because he's Mitchell Johnson, Jonesboro school shooter. That's my opinion."

"They were looking at the fact that because he was a juvenile when he got involved in the Jonesboro school shooting and, essentially, got out when he was 21 years old, that didn't sit well with a lot of people. And I think they thought this would be probably the most powerful charge," Schisler said.

While out on bond for that case, Johnson was arrested again in 2008. The Associated Press reported that Johnson admitted to taking a debit card left by a customer at the Arkansas gas station where Johnson was working. Johnson proceeded to use the card at the gas station and at a fast-food restaurant, and had marijuana on his person at the time of his arrest.

Johnson was sentenced to 12 years after being convicted in that 2008 incident and was to be eligible for parole in 2011, but then faced four more years for the earlier drug and weapons conviction from the traffic stop, the AP reported. Schisler confirmed the account. Court records show he was released in July 2015 into the custody of the U.S. Probation Office for the Southern District of Texas and placed in a drug rehabilitation program. The office did not respond to ABC News' multiple requests for comment.

HIDDEN IN PLAIN SIGHT

Photos of Golden, who may or may not still go by his changed name, were released at the time of the shooting. His 11-year-old mug shot comes up readily in Internet searches.

ABC News contacted 10 phone numbers listed for various relatives of Golden. His grandmother declined to comment and three of his previous lawyers told ABC News that they had not spoken to him in years and did not have any way to contact him. Johnson’s mother declined to comment when contacted and Johnson’s father said they have been estranged for years and he has no idea where his son is now.

Science teacher Spencer said there had been speculation in Jonesboro that Golden started attending a local university after his release in May 2007. The registrar for the University of Arkansas Community College at Batesville, which is about 60 miles west of Westside, confirmed to ABC News that an individual named Drew D. Grant attended the school from August 2007 until December 2009.

Johnson has a more recent mug shot floating around as a result of his subsequent arrests. On top of that, he was subject to a videotaped deposition in 2007 as part of the civil suit filed on behalf of the relatives of the victims. That taped deposition was released publicly, along with the transcript, but that wasn't the case with Golden.

Danny Glover represents Golden in the civil suit filed against the pair by the relatives of the victims. Glover told ABC News that while the suit is "still open, it's just been sitting there for decades – well, at least one decade."

The Craighead County Circuit Court clerk told ABC News that the latest action in the suit came in 2013 when Golden's grandfather was removed as a defendant in the suit because he died in 2012. When ABC News contacted Bobby McDaniel, the lawyer representing the victims' relatives in the suit to ask what was stalling the suit, he said it was the fact that Johnson was still in jail.

When told that Johnson was released in July, McDaniel said that he intends to "get a trial date so that we can obtain a moneyed judgment against both defendants for both compensatory and punitive damages. Punitive damages cannot be set aside in bankruptcy. I do not expect to collect these judgments but I want them hanging over their heads."

Glover confirmed that Golden was deposed as part of that suit but it was sealed by court order "because it had personal information about his whereabouts and identity that the court felt didn't need to be disclosed for his protection."

After the release of Johnson's deposition, Glover said Johnson received death threats.

"[Golden] changed his name at some point, so the court prevented the dissemination of that information and that was part of the court order," Glover said of Golden.

By contrast, in Arkansas, sex offenders are required to update the state either twice or four times a year with their addresses, vehicle information, physical characteristics, place of work, identifying codes for all of their electronic devices, and all of their email accounts and user names, according to Brad Cazort, the administrator of the repository division of the Arkansas Crime Information Center.

"I am very critical that our judicial system will allow mass murderers to live anywhere they want without their identities being known, their crimes known, or the families in those areas to be aware of who is living near them," McDaniel told ABC.

Both McDaniel and Mitch Wright, the husband of Westside teacher Shannon Wright, who was fatally shot in the back, say they believe the restrictions placed on these criminals pale in comparison to offenders who have not committed murder.

"I think that if a sex offender has to register as a sex offender, then I believe a person that's able to commit the crimes that were as bad as these were… then yes I do believe it's in the public's interest to know the name that he is going by," Wright, 50, told ABC News of Golden.

The privacy awarded the shooters because of their ages is understandable to some, though not necessarily appreciated. Spencer, the science teacher, said it seemed uneven that "they [the shooters] could find anything out they wanted to about us" but Golden and Johnson are "protected."

"They shouldn't have any rights. They shouldn't have the right to be out, to get a family, to have a gun and have a normal life like they didn't ever do anything wrong," she said.

Brandi Varner, whose 11-year-old sister Britthney was killed in the shooting, said that "every time of year around this time is a slap in the face" because she is reminded of the anniversary and that her sister's shooters are free.

"This guy is living the life that your sister dreamed of," said Varner, now 31, who was 14 at the time of the shooting.

SEARCH FOR ANSWERS

Videotaped confessions or manifestos released online have given subsequent shooters outlets to explain themselves and their actions, but such clarity was never available in the case of Jonesboro.

"I think [the deposition was] a matter of getting answers," lawyer Glover said. "The lawsuit is to get money to recover compensation for the victims, but I don't think anybody ever believed that there's going to be any great recovery."

In Johnson's deposition, he described Golden as being the one who initiated the shooting.

"He was, like, 'I've been thinking about doing some scaring of some people because I'm tired of them playing with me,'" Johnson said, according to an account of the deposition by The Arkansas Times.

For his part, Glover said Golden "seemed to be a fairly mild-mannered kind of young man."

"He had a good attitude," Glover said. "I think he regrets what happened and really can't explain what happened. Of course, he was 11 when it happened. … At 11, it's hard to imagine why somebody would do that."

The public defender who represented Golden in the original juvenile case in state circuit court, Val Price, had no comment when asked by ABC News to describe Golden.

Wright, who was left to raise their toddler after his 32-year-old wife's death, said he wishes Golden and Johnson were still behind bars, "but I have reached a point in my life where it's in God's hands."

"Here's how I raised my son: He was two and a half and I could have raised my son in a home filled with hate and anger, and I could have let that hate and anger destroy him and me and destroy our souls, and that could have prevented us from ever seeing her again," Wright said.

"And what I told him was this: these two boys could truly repent and they can be forgiven for their sins and they could go to heaven and we could go to hell if we let this hate and anger eat us alive."

Science teacher Spencer said the search for answers used to "drive me crazy." The year after the shooting was the hardest, and not just because of timing but because she had Johnson's younger brother in her class that year.

"When his mother came for a parent-teacher conference, I just point-blank asked her. I said, 'I had a hole in my purse. Was he trying to shoot me too, because he shot two teachers?'" Spencer told ABC News.

"She said that Mitchell said that Andrew told Mitchell to shoot all the teachers.”

While Johnson's mother declined to comment for this story, she did apologize as part of a town hall special ABC News hosted in 1999. Scott Johnson, Mitchell's father, told ABC last week that he has not spoken to his son since he was arrested in 2008 and was aware that he had been released but did not know where Mitchell was living now.

"I've kind of let it go," you know," Spencer said of the boys, "because I won't ever know and don't particularly want to see them and ask them."

ABC News' Lauren Pearle contributed to this report.