Dad fighting deportation has lived in a church for 6 months to keep his family together

Desperate to stay with his three children, García entered sanctuary on Nov. 13.

PHILADELPHIA -- It has been more than six months since Javier Flores García set foot outside the Arch Street United Methodist Church in downtown Philadelphia. Sometimes, as the other parishioners make their way through the big double doors after Sunday Mass, he lets himself walk with them all the way to the threshold.

“It’s very hard to watch people leave with their families when I know I have to go back down below, to the same place,” García told ABC News in Spanish.

Outside, tourists snap photos in front of City Hall, and commuters rush to work. In the six months he has been staying in the church’s basement, fall has turned to winter and winter to spring.

“Sometimes, when there is no one in the church and my wife comes to bring me food or to eat with me, I go up and open the door,” he said. “It gives me such nostalgia to see all the people walking outside when I know I can’t leave. That’s the hardest thing.”

But for García, a 40-year-old undocumented immigrant from Mexico, the risk of walking outside is too great. It would take only a few minutes for agents from the nearby Philadelphia field office of Immigration and Customs Enforcement to arrive and arrest him — and eventually deport him. His ankle bracelet tells them where he is at all times. That’s why, since Nov. 13, he has been living in a makeshift apartment in the church. Places of worship are a category of locations deemed sensitive by ICE, meaning the agency typically avoids conducting enforcement actions in them.

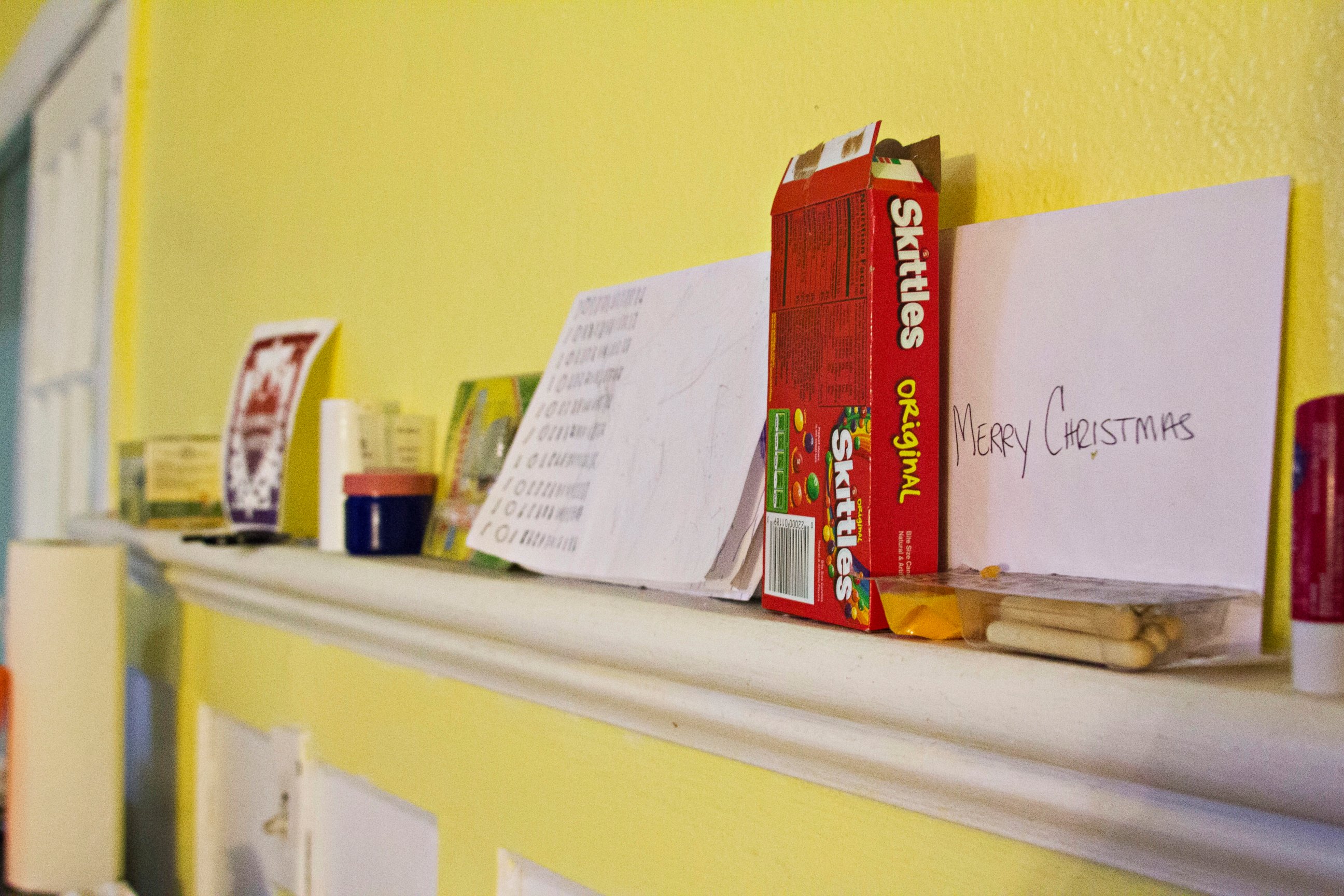

In García's small world, little has changed in six months. He spends his days doing odd jobs — painting, cleaning bathrooms and setting up tables for the free meals the congregation serves to homeless people and veterans. In his room, a small TV often flickers in the corner, on but muted. He has a desk with Christmas cards, a mini-fridge with food and in one corner, a narrow bed.

It’s in this room that he said he spends his days waiting for the outcome of his petition for legal status in the United States.

“Every day, it’s the same, wondering … when they’re going to decide to approve or deny it,” García said. “That is what I find myself thinking about — when, what day and how they will decide.”

The alternative is to go back to Mexico, a country he hasn’t called home in 20 years, without his three children, all U.S. citizens. García said he crossed the border on foot in 1997. He then met his wife, Alma Lopez, who is also undocumented, and together they have raised three children: Adamaris, 13; Javier, 5; and Yael, 2.

“I came here, but they started their lives here in this country. It’s theirs, and they have to continue here,” he said. “It’s hard, but I think it’s worth it to keep fighting. Not for me but for my children. It’s not fair to them to have their well-being taken away.”

But this is his last chance to legally stay with his family, according to his attorney, Brennan Gian-Grasso, 39. Authorities have deported García four times — in 2007, in 2013 and twice in 2014 — Gian-Grasso said. Each time, García has managed to cross back into the U.S. on foot.

Now Garcia is waiting to hear whether he will be granted one of only 10,000 visas that are reserved each year for immigrants who are victims of crimes and agree to help law enforcement solve them. Nearly two years after his U visa petition was filed, he has no choice but to continue to wait.

“This is really his only option right now,” Gian-Grasso told ABC News. “This is his shot.”

Vying for 1 of 10,000 visas

García’s fate hangs entirely on a visa dependent on one of the worst days of his life. On March 18, 2004, he and his brother were attacked and stabbed with box cutters in Bensalem, Pennsylvania, by two other undocumented men.

According to an affidavit of probable cause filed by the detectives in the case, the brothers were transported to the hospital after “suffering stab wounds and numerous lacerations” from “grayish colored box cutters.” The two men who attacked them were charged with aggravated assault.

“While he was in the hospital, Javier worked with police to let them know all the details he could,” Gian-Grasso said. “He was willing to testify, but because of his cooperation from the very get-go and his ability to identify the people who hurt him, they ended up accepting plea deals to aggravated assault, served jail time and were ultimately deported.”

U nonimmigrant visas, created in 2000, are reserved for victims of crimes who have suffered physical and mental abuse and are willing to cooperate with law enforcement in the investigation or prosecution of those responsible, according to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. U visa holders may eventually petition for permanent residency and help their family members stay in the U.S. as well.

The number of U visas granted hovers around 10,000 each year, according to USCIS. But the number of U visa petitions nearly tripled from 2010 to 2015, from 10,742 to 30,106, according to USCIS.

Susan Bowyer is the deputy director of the Immigration Center for Women and Children in Oakland, California. She said the center helps file about 1,000 principal U visa petitions each year.

“Law enforcement agencies consistently tell us that the U visa is a great way to build — or repair — bridges to immigrant communities,” she told ABC News in an email.

The increase in petitions can be attributed to increased awareness among immigration attorneys and their clients, she said.

“People learn about it from other people that got U visas. We had a client come in who was robbed on a street corner, and a woman leaned out the window above him and said, ‘Call the police. You can get a U visa,’” Bowyer added.

But that wasn’t the case for García, Gian-Grasso said. No U visa petition was filed on his behalf until more than 10 years after he was attacked, when he was already in the Pike County Detention Center, awaiting deportation.

Now that attack so many years ago is his only chance to stay with his children.

“The only reason Javier has any possibility for immigration relief is because he had the unfortunate experience of being the victim of a pretty heinous assault,” Gian-Grasso said. “Up to that point, there have been a lot of missed opportunities with him being able to apply with previous immigration lawyers.”

But before USCIS may consider his U visa petition, Gian-Grasso said, García needs to be granted a waiver of inadmissibility because of his previous deportations. And while his attorney doubts his U visa petition will be denied, he has been denied a waiver of inadmissibility twice.

“If the waiver is granted, I don’t see any issue. There has never been any statement that his qualifying crime was insufficient or that he didn’t cooperate,” Gian-Grasso said. “The real crux of the issue right now is whether his waiver will be granted or not.”

Gian-Grasso said he filed a motion to reopen García’s request for a waiver of inadmissibility with USCIS, challenging the grounds for its previous denial. That motion has been pending since August 2016.

‘A downward spiral for the family’

García’s detention started in May 2015, when ICE agents were waiting for him as he left for work. It was about a year since he had entered the U.S. most recently, in 2014. He said his older son and daughter watched as ICE agents handcuffed him at the family’s home. He was sent to a detention center more than 130 miles from his family in Philadelphia.

The family reached out to Juntos, an immigrants’ rights organization, for help. Olivia Vasquez, a community organizer with Juntos, said that at one point, the García children tried to sneak off and hitchhike to the detention center where their father was held.

“His daughter, who was 12 at the time, was desperate to see her father, so she had said, ‘Come on, little brothers, let’s go see Dad,’” Vasquez told ABC News. “Alma came home and called the police, and they found them a few miles away.”

As the months went by, it became clear that the children were increasingly affected by their father’s detention, Vasquez and Gian-Grasso said.

“There was just a downward spiral for the family. His daughter tried to commit suicide. His son ended up becoming increasingly psychologically affected by his detention. A whole bunch of really bad things happened,” Gian-Grasso said.

Adamaris said her father’s detention was one of the most difficult times in her life.

“It affected me really bad, because I didn’t know if they were going to send him to Mexico or if I was ever going to see him again,” she told ABC News. “I had trouble in school. My mom sometimes didn’t even want to come out of her room.”

García said he was desperate to help his family, so he decided to seek parole, which can be granted at ICE’s discretion. After three denials, his request was approved in August of last year, and he was released with an ankle bracelet to monitor his movements. His parole was set to expire on Nov. 14, but in the 90 days García was out of detention, nothing changed with his U visa petition. Worried about his family’s well-being if he went into detention again, he said, he took matters into his own hands.

‘We felt like we are actually living our faith’

García, a soft-spoken man, was not previously a member of the Arch Street United Methodist congregation. He said he has never really liked public speaking or being the center of attention. But on the Sunday after Election Day, during a regularly scheduled service full of people, he stood up and formally asked for sanctuary. He was going to be detained the next day and deported soon after, his attorney said.

“It wasn’t easy to find a church,” he said. “Many churches closed their doors to us. But thank God, this one opened theirs.”

The logistics of his sanctuary were the product of weeks of planning between the García family, Juntos and the church, the Rev. Robin Hynicka told ABC News. Arch Street United Methodist had been a member of the New Sanctuary Movement of Philadelphia for the past six years, Hynicka said, and a longtime Juntos ally. So when García’s case came before him, Hynicka said, he didn’t hesitate.

“When the call came for Arch Street to consider becoming a physical sanctuary for Javier, I simply put out a message to about 40 leaders in our church. I basically said, ‘I don’t think this is a question of will we do this but how we will do this.’ And all of them agreed,” Hynicka said. “Within two weeks, we had a room ready.”

When García stood up during Mass, holding little Javier, the atmosphere in the church was something special, Hynicka said.

“We felt like we are actually living our faith. We aren’t just talking about doing justice and loving our neighbor. We’re actually loving our neighbor and doing justice right now, today,” Hynicka said. “There was a real sense of community, a real sense of a peaceable kingdom that has power.”

Churches have served as sanctuaries for centuries, Hynicka said, and the Sanctuary Movement in the U.S. began in the 1980s, when churches opened their doors to Central American people fleeing civil wars.

ICE said it views places of worship, schools and hospitals as sensitive locations and maintains a policy of avoiding enforcement actions there.

“The Department of Homeland Security is committed to ensuring that people seeking to participate in activities or utilize services provided at any sensitive location are free to do so without fear or hesitation,” ICE officials told ABC News in a statement. They declined to comment on García’s case in particular.

But immigration officials know where he is at all times because of his ankle bracelet, Gian-Grasso said.

“Javier, when he went into sanctuary, said ‘Look, I’m not a fugitive. I’m not hiding anywhere. I’m going to tell you where I’m going to be. But I have to do this for my family.’ And this is fundamentally a nonviolent form of protest,” Gian-Grasso added.

‘Their parents are legal here, but not all of us have that privilege’

The decision to stay in sanctuary hasn’t been easy. García said he used to earn $2,800 a month as an arborist and spent his days working outdoors. Now he does odd jobs in the church, and his family relies on donations to make ends meet.

Lopez has had to care for the children largely on her own, she said.

“It’s affected us very much — economically, physically and morally — especially the children,” she told ABC News in Spanish. “I haven’t been able to look for work because of the children. I have to take them to therapy. I have to take food to Javier.”

While Lopez is also undocumented, she doesn’t have an active deportation order against her.

Adamaris said that while having her father in sanctuary has been much better than having him in a detention center, her life is very different from her classmates’.

“Even though we can visit him sometimes, he is still far away. I have to go to school, and sometimes my mom has to pay more attention to my brothers and my dad than to me. So basically, I don’t get the same attention,” Adamaris said.

And few of her classmates understand what it’s like to live with that stress, she said.

“I don’t think they know how it feels because they have both their parents there. They don’t know to experience that because their parents are legal here, but not all of us have that privilege,” Adamaris said.

García said his children struggle with post-traumatic stress disorder, which was diagnosed by therapists, from his time in detention.

“It’s very hard for them psychologically. Even now, when they see police, they assume they are here for me,” García said. “Recently, after I came here, my older son came to visit me, and he saw the police lights pass by the window, and he said, ‘We have to run. We have to go.’ I told him, ‘Don’t worry. We’re safe here.’”

García said that as a parent, it’s hard to see his children live with such fear. Little Javier often stays overnight with his father at the church and cries when he goes back home without him.

“Normally, he lives with me here. He can leave for a day, two days, but normally but it’s just one day he spends at home,” García said. “His fear comes when night comes.”

“He calls me and asks, ‘Are you OK? Are you sad?’ I tell him, ‘No, I’m content because you are at home,’” García said. “It’s very hard. But now is not the time to fall apart. We have to be strong because if I fall, my family falls.”

The family has been working to gradually get Javier to spend more nights at home with his mother and siblings in preparation for him to start kindergarten. But he is still waiting for his father’s future to be determined.

“He says to me, ‘When you can leave, I will go to school,’” García said. “It’s very hard to see all of this, but I can’t give up now.”

‘Why would I give it all up?’

Since taking office, President Donald Trump has vowed to crack down on so-called sanctuary cities, including Philadelphia. García said he knows he is vulnerable.

“The fear is always there. With the new president, anything can happen,” he said. “But I am not going to give up because of the fear.”

ICE said it has stepped up arrests by more than 37 percent under the Trump administration. From Jan. 22 to Apr. 29, deportation officers arrested 41,318 people. The agency said nearly 75 percent of the people it has arrested since Trump took office are convicted criminals, although the majority were not convicted of violent crimes.

García, who was convicted of DUI in 2004 but was given probation rather than jail time, said many people have asked him why he doesn’t go back to Mexico and take his family with him. But because his children are U.S. citizens and they have greater opportunities here, he feels compelled to stay.

“Why would I give it all up? Why would I give it up for me, not thinking about my children and their future here?” he said. “If they deport me, I will return. It doesn’t matter how long it takes me. It could be one or two years. But I am going to return.”

And though ICE has policies in place to avoid conducting enforcement actions in churches, agents have leeway in how they interpret those policies, according to David Bier, an immigration policy analyst at the Cato Institute, a think tank focused on free markets and limited government.

“What I see happening is that there is a lot of legal language being used that’s very carefully crafted to say that we’re not going to target people in certain areas, but then they’re targeted just outside of those areas,” he told ABC News. “So the minute they walk out of that church or the minute they walk out of the courthouse, you have agents waiting for them.”

Bier said even when then-President Barack Obama told ICE in 2014 to focus on deporting convicted criminals, ICE’s discretion led to more removals. That could be the case once again under Trump.

“ICE was interpreting that as broadly as possible and using every possible means to effectuate more removals,” Bier said. “That resulted in an unprecedented number of deportations. I think that, really, by giving them the flexibility, by giving them this discretion to decide that in certain cases, you can violate these restrictions, in certain cases you can go after people who haven’t been convicted of a crime, that’s pretty much opening it up to have them do it whenever they want.”

With his history of immigration violation convictions, Hynicka knows that ICE could choose to go for García. But he said he hopes agents continue to respect the centuries-old practice of regarding places of worship as sanctuaries.

“We have an open door every day. ICE knows where Javier is,” Hynicka said. “I would really state clearly that we are a church doing our work, we are church honoring our sacred call to be a loving neighbor and doing justice. It would be a tremendous mistake if ICE would come to the church or any other church or community of faith that’s providing sanctuary.”

“We have procedures in place. We know what the law is. Javier knows what the law is. We know what our rights are,” he added, saying that he would ask agents for a warrant signed by a federal judge.

Gian-Grasso said that he will do everything in his power legally to protect García if ICE chooses to enter the church but that the options are limited.

“I could provide more information for a stay of removal, and there’s a lot of things I would have to do in terms of filing,” Gian-Grasso said. “What my inclination is, though — if he were forcibly removed from the church right now, it would be very difficult to stop his removal.”

For now, García can only wait to see whether his petition is approved. But his wife and children know just what they will do if he is able to walk out those big church doors.

“That day, we will have all of our family members come over, since they have seen how hard we have worked for my dad to have his visa, and also our neighbors, because they are hoping to see him soon too,” Adamaris said. “This time, we would like him to actually experience things like a legal citizen.”