Burning Man Festival Reaches Deal to Stay Put

Nevada's Burning Man has reached a legal settlement with Pershing County.

Nov. 13, 2013 -- Good news for fans of Burning Man, Nevada's annual new-age festival: It won't have to move. It can burn on for years, right where it is now, in Pershing County's Black Rock Desert, in the far northwestern corner of Nevada.

Burning Man moved once before, in 1991, from its birthplace (a San Francisco beach) to Black Rock's desert wastes. It lived there happily until a year or two ago, when, according to Burning Man's side of the story, Pershing County started trying to exact what the Man considered onerous fees for county services.

According to a fact sheet released by the festival's owner, Black Rock City LLC (BRC), fees charged by the county for providing law enforcement services rose from $66,000 in 2006 to $154,000 (plus $7,000 for vehicle usage and $14,000 more for prosecution costs) in 2011, and to just under $400,000 for 2012.

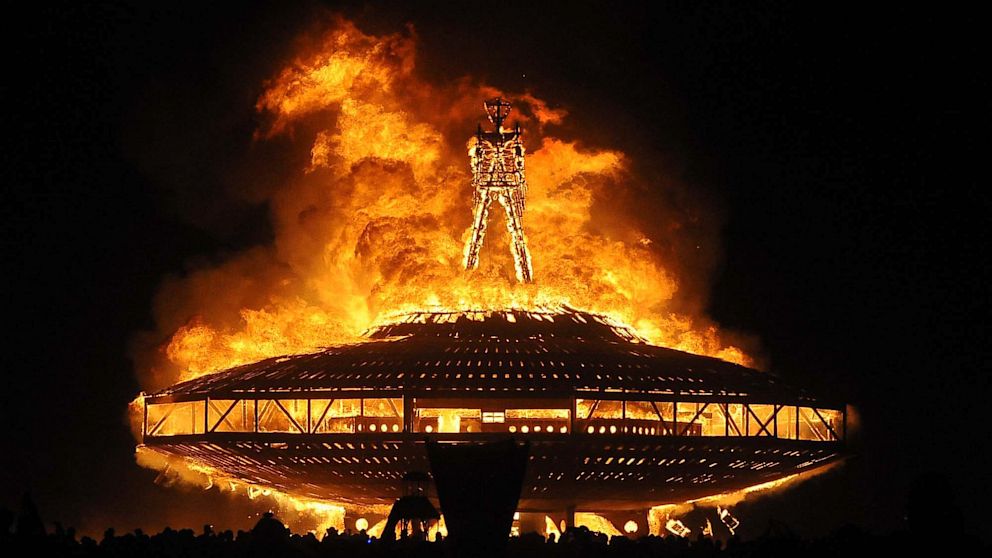

Burning Man: what is it, exactly?

In August 2012, BRC filed suit to block future fee increases. Said festival founder Larry Harvey in a statement related to the suit, "These fees are arbitrary and capricious. It is wrong for the county to bully us in an attempt for it to balance its books. We are being treated like a piggy bank. We do not think that this government or any government has the right to do this."

BRC estimates the festival's positive economic impact on the area at $35 million a year—money spent by Burning Man's tens of thousands of attendees. In the weeks before, during and after the festival, the Reno-Tahoe International Airport receives about 15,000 festival-bound visitors from 30 nations. The festival has made charitable contributions of over $200,000 a year to local schools and community organizations.

Might a disgruntled Burning Man eventually have packed up and moved? As of yesterday, that possibility has been taken off the table: BRC and Pershing County announced they had arrived at a mutually satisfactory resolution of their lawsuit. "This is a very favorable outcome for all parties," says Raymond Allen, government affairs representative for BRC. "The terms address all of BRC's and the county's concerns."

"The resolution of the suit bodes well for the sustainability of Burning Man," said a festival spokesperson.

Burning Man and Pershing County settle suit

What would have been the county's 2013 fee for law enforcement--$240,000—has been reduced, after the law suit, to $200,000. Future fees, according to the settlement, are to be figured according to a sliding scale, based on festival attendance. About 65,000 people attended last year.

William Headaphol, 58, of Rancho Santa Fe, Calif., attended, along with his 17-year-old son.

Headaphol tells ABC News it's easy to see how Pershing County could view the festival as a piggy bank. "There's nothing else around," he says, referring to the desolate setting. BRC does not report revenue or profit, but Headaphol says the figures would not hard to estimate: He multiplies the cost of a ticket ($400) by 65,000, and gets $26 million. If you deduct from that $20 million in expenses (which BRC does report), then it looks as if Burning Man, having settled its dispute with the county, should be happy here for years to come.

Headaphol, who has attended twice, has a special fondness for the festival. There's an absence of what he calls "hawking": inside, nothing is for sale except ice and coffee. There are no concessions, no advertising.

"It's a gifting society," he says. "If somebody does something nice for you, you do something nice for them." He brought along with him several bicycles, and loaned one to a woman that he met. The two went bike riding, and she, to show her appreciation, gave Headaphol a lemon.

The festival has only three rules, which, he says, combine to create a unique and refreshing society: "radical self-reliance; radical inclusion; and gifting—if you help somebody, they can give you a gift."