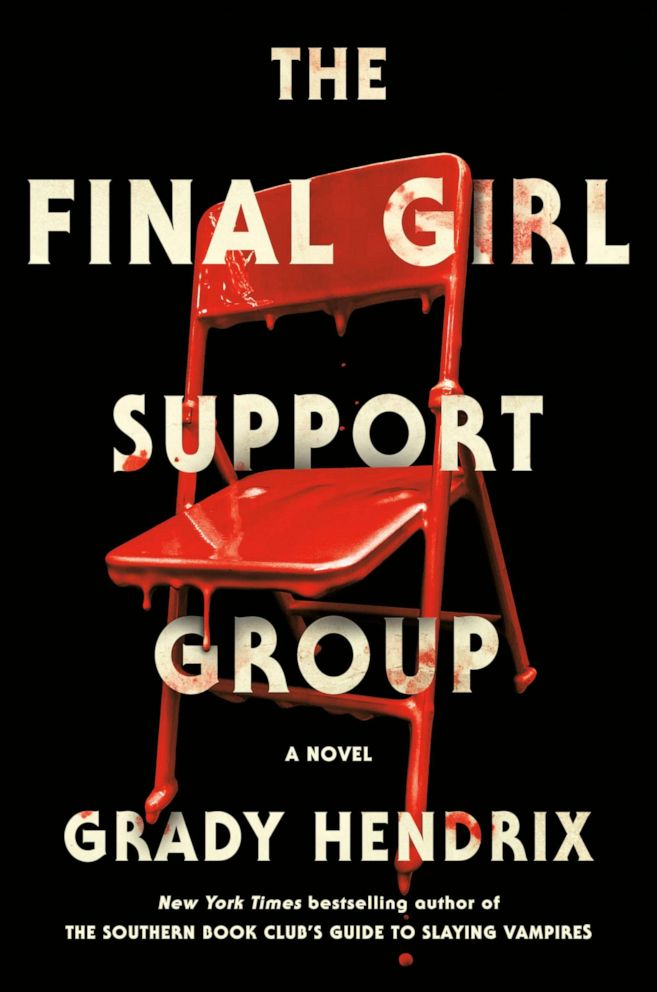

'GMA' Buzz Picks: Grady Hendrix's 'The Final Girl Support Group'

In horror movies, the final girl is the one who's left standing at the end.

If you've finished our "GMA" Book Club pick this month and are craving something else to read, look no further than our new digital series, "GMA" Buzz Picks. Each week, we'll feature a new book that we're also reading this month to give our audience even more literary adventures. Get started with our latest pick below!

This week's Buzz Pick is "The Final Girl Support Group" by Grady Hendrix.

In horror movies, the final girl is the one who's left standing when the credits roll. But what happens after?

From chain saws to hockey masks, New York Times bestselling author Grady Hendrix explores the classic horror trope in "The Final Girl Support Group," a nostalgic homage to and critique of '70s, '80s and '90s slasher films, like "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre," "A Nightmare on Elm Street" and "Scream" that's perfect for fans of both horror and suspense. It follows six "final girls" who have met for group therapy for years. They made it through the worst night of their lives, but that was only the beginning.

Lynette Tarkington is a final girl who survived a massacre. For more than a decade, she's been meeting with other final girls and their therapist for group support, working to put their lives back together. Then one woman misses a meeting, and their worst fears are realized -- someone knows about the group and is determined to rip their lives apart again, piece by piece. But the thing about final girls is, they will never, ever give up.

"'The Final Girl Support Group' has been with me for years -- a project I've written, rewritten, added to and changed as my life has changed, almost like a diary," Hendrix said. "It's a book about survival, finding reserves of strength you didn't know you had, and our mad fight to make it through the night. Final Girls are one of horror's most enduring tropes, and this book contains everything I wanted to say about the horror I grew up with in the '80s and '90s and how it taught me to never quit."

Like all of Hendrix's novels, "The Final Girl Support Group" is wildly fun to read. It's creepy and thrilling and full of Hendrix's trademark humor and heart.

"It's the perfect thriller to take with you to the beach this summer, or for a long hike into the woods," Hendrix told "Good Morning America." "Just remember, bring your sunscreen, wear your running shoes and watch out for ax murderers."

"The Final Girl Support Group" is available now. Get started with an excerpt below and get a copy here.

Read along with us and join the conversation all month long on our Instagram account -- GMA Book Club and #GMABookClub

*****

We don't stick around, we scatter. We're final girls; taking care of ourselves is what we do. Upstairs it's one of those bright, autumn Los Angeles days where nothing bad seems possible. We could be a bunch of soccer moms leaving church after planning a really terrific carnival with face painting and pony rides. Marilyn is on the phone all the way to her E‑Class Mercedes. Julia takes the elevator to the parking lot, puts her chair in the back of her minivan, and swings her way to the driver's seat on crutches. Heather cuts across front yards and driveways, wandering off down Alameda. Most people wouldn't spot the only detail that makes us different: Dani standing by her truck, a matte‑black Beretta Nano in one hand, holding it behind her leg, watching over everyone to make sure we all get out safe.

I'm fragile and plastic and full of static, but I have my system and after all these years it takes over and keeps me safe. I walk to the bus stop, my suburban ESP on high. I stick to the street, staying on the outside of parked cars, avoiding the sidewalks, keeping my head on a swivel, checking my corners, assessing threats.

My focus keeps getting broken by what Julia said. I'm watching out for people following me, for cars with out‑of‑state plates, for men in sunglasses with their hats pulled low, but my mind keeps arguing with Julia.

I'm not the problem. Is the man sitting in that parked car only pretending to be on his cell phone? Why did he slide lower when I spotted him? I'm not the crazy one. I'm not the reason we all keep coming to group. Heather is the one we have to watch out for. She's the one who needs us. I'm the sane one. I'm the safe one. That Honda making a right turn has Utah plates. I memorize the number in case it comes back around the block. I'm watching for tinted windows. I'm watching for motorcycles. I'm not thinking about what Julia said. I'm not thinking about how no one argued with her. I'm watching for vans. Don't get me started on vans.

I don't relax until I'm on a city bus. On the street, anyone can come at you from any direction. On the bus, there are limited angles of attack. They're advertising a horror movie overhead and the red signs makes me think of Adrienne, but I need to stay focused. Some boys with instrument cases sit at the back, heads bowed, engrossed in something on one of their phones. Men don't have to pay attention the way we do. Men die because they make mistakes. Women? We die because we're female. Look at Adrienne. No, look at their shoes. Memorize their faces, their clothing, their shoes. Especially their shoes.

I take the bus all the way downtown, get off at Olive and take major streets to a nearby multiplex. Outside, I put my back to the wall and pretend to check my phone. Anyone following me is going to have to either stop short or pass me by. Bright white Nikes go through my field of vision, shined‑up black Rockports, fat‑laced Timberlands; if someone's following they can change their jacket or their hat, but it's a whole lot harder to change their shoes.

I don't need to look at the roofline or check windows. It's shoes I have to worry about because the monsters in our lives prefer to get up close and personal. A sniper attack would be like mailing me their penis. They need to touch me.

After I buy my ticket I stand in the lobby, back against the wall, and watch shoes again. Betsey Johnson ballet flats, beige Uggs, confetti‑colored children's sneakers, Sperry Top‑Siders.

My movie is on previews. I sit in the front row, then turn back around like I'm looking for my date. It's a computer‑animated children's movie, so it should be easy to spot an unaccompanied adult male. It's not impossible, but chances are low that anyone following me would bring a child for camouflage. I keep my eyes on the redheaded muscle shirt with brunette twins and the blond male with the beard and the little boy. Both of them scanned the theater when they came in, like they were looking for someone.

When the movie finally begins I break for the emergency exit to the left of the screen, dash down the stairs, and come out on the street. I don't see the redhead or Mr. Beard. I do see another Honda with Utah plates but it's a different number. I memorize this plate, too, noting its dusty windows and mud‑spattered bumper, the Triple A sticker on its back windshield. I catch a bus to the Beverly Center.

Riding the bus, I sit as close to the driver as possible. At every stop I watch shoes. I try to stay focused -- Doc Martens, Caterpillar steel tips, scuffed Nikes, white nursing shoes -- but Adrienne keeps hijacking my train of thought. She and Julia have thrown me off my game.

Adrienne was the first and best of us. She's the reason most of us joined group. Her crisis set the template. Plenty of women survive violence, but what makes those of us in group our own toxic little category of final girl is that we killed our monsters, or we thought we did, and then it happened to us again. We all thought Adrienne was the only one who never got a sequel, but we were wrong, because thirty‑three years later, here came her monster one more time, back to finish the job. Adrienne thought she was safe, but she was wrong. What else were we wrong about?

*****

Excerpted from "The Final Girl Support Group" by Grady Hendrix, published by Berkley, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2021