Children with genetic deafness have hearing restored with gene therapy: Study

Researchers say deafness can affect children's brain development.

Children with hereditary deafness regained their hearing thanks to a type of gene therapy, a new study published on Wednesday found.

In a clinical trial, co-led by investigators from Mass Eye and Ear, a specialty hospital in Boston, six children who had a form of genetic deafness called DFNB9 were examined.

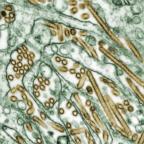

This deafness is caused by mutations of the OTOF gene. This mutation fails to produce a protein known as otoferlin, which is necessary for the transmission of sound signals from the ear to the brain, according to the researchers.

The trial -- which began in December 2022 -- took place at Eye & ENT Hospital of Fudan University in Shanghai and involved the use of an inactive virus carrying a functioning version of the OTOF gene.

It was carefully introduced into the inner ear of the six children at differing doses, and they were observed for 26 weeks.

Results, published in The Lancet, showed five of the six children, who were classified as having total deafness, recovered their hearing "and the restored ability to conduct normal conversation," according to a release.

Researchers say this is the first human clinical trial to use a gene therapy for treating this condition, with the most patients treated and the longest follow-up period.

Related Stories

"For us, it really is a milestone," Dr. Zheng-Yi Chen, an associate scientist in the Eaton-Peabody Laboratories at Mass Eye and Ear and associate professor of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at Harvard Medical School, told ABC News. "We are absolutely thrilled ... It will have a huge impact on the field."

"Hearing loss affects so many people and, up to now, there's no single FDA-approved drug to treat any type of hearing loss, including generic hearing loss," he continued. "So, this is the first time where a brand-new type of gene therapy approach can actually be used to treat the children who are completely deaf and regain the function of hearing."

Chen said that when children are unable to hear, this can affect their development and have long-lasting impacts. He said this is why it's recommended for infants to have hearing screenings shortly after birth.

"Communication is essential to children's development," he said. "If children cannot hear or cannot communicate, especially in the first three years of their lives, their brain development actually will be severely affected."

Chen said the next steps are to expand the study to enroll more patients for a larger clinical trial and to follow them for a longer period of time to ensure that the treatment works, with the hopes that it could be expanded to treat more types of genetic deafness.

The findings from the clinical trial will be presented Feb. 3 at the Association for Research in Otolaryngology Annual Meeting in Anaheim, California.

It comes on the heels of a report regarding the first person in the U.S., an 11-year-old boy from Spain, who was treated with a gene therapy, made by pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly, to reverse his genetic form of hearing loss, according to his doctors at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.