Doctors advise how to get kids 5-11 boosted when COVID vaccination rates in US are low

Only about 29% of this age group are fully vaccinated.

Two weeks ago, federal health officials authorized COVID-19 boosters for children between ages 5 and 11.

Doctors think it will be a challenge to get this age group boosted when uptake for primary doses of the vaccine is so low, but they say town halls, providing information in multiple languages and offering the boosters in pediatricians' office could help.

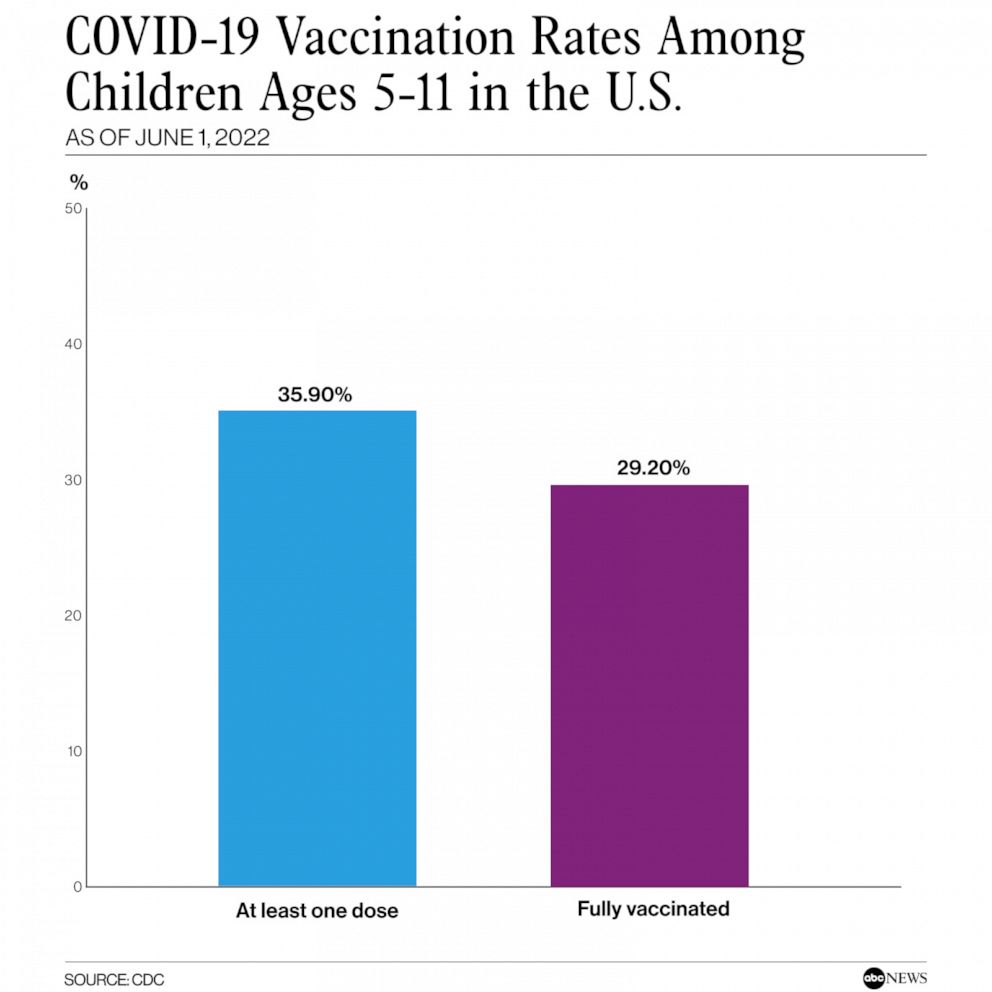

As of Thursday, only 35.9% of children under age 12 have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

An even smaller percentage, 29.2%, have been fully vaccinated.

"It absolutely should be much higher," Dr. Stanley Spinner, chief medical officer and vice president of Texas Children's Pediatrics and Texas Children's Urgent Care at Texas Children's Hospital, told ABC News. "Children can get seriously ill from COVID and children, even if they have very mild symptoms, are extremely proficient at spreading infection."

And hesitant parents don't seem inclined to increase these rates any time soon.

An April 2022 poll from the Kaiser Family Foundation found 32% of parents of 5- to 11-year-olds said their children will definitely not get vaccinated.

What's more, 12% said they will only get their child vaccinated if it's required for school and 13% said they want to wait and see.

How to talk to parents about boosters

Doctors stress it's important that children not only get a primary series but a booster too so the immune system can get a "reminder" of fighting off COVID-19.

"What the science has shown is that our immunity starts waning around the fifth or sixth month after our primary series," Dr. Shaquita Bell, medical director of the Odessa Brown Children's Clinic, a community health center operated by Seattle Children's, told ABC News. "Our immune system needs reminders and that's what I think of the booster as. The booster is a reminder to help your body remember how to fight off the infection."

To help alleviate parents' concerns, Dr. Lalit Bajaj, chief quality and outcomes officer at Children's Hospital Colorado, said he and his colleagues hold frequent town halls about the vaccine, sit on panels for community organizations to discuss the vaccine and provide information in other languages including Spanish.

"It's normal to say, 'I don't understand this, I don't know this, this seems brand new,' and so you do a lot of listening as well," he told ABC News. "So, we help folks really better understand what they need to learn to alleviate safety concerns."

Spinner said his hospital is offering the vaccine at all outpatient facilities rather than specific hospital sites to increase vaccination and booster rates among children.

Physicians and staff also speak to parents every time a child comes into the office for a visit about the benefit of the COVID-19 vaccine and booster -- even offering to administer the shots right then and there.

"I can tell you it's made a huge difference," he said. "When we would talk about getting the vaccine the family would have to go to one of the three hospital campuses [and] they often wouldn't do it. But when you have the conversation in the office and you have the syringe ready to go … we are able to do a lot better in terms of getting these kids vaccinated."

Why parents are hesitant to vaccinate their children

Bell said many adults still believe COVID-19 doesn't impact kids severely.

"[They believe children] are at less risk of severe illness, less risk of death and, because of that, I think people are less convinced that the vaccine is necessary for children," she said. "Whether or not the risk of getting the disease is lower in a child than it is in an adult, there is still a risk of getting the disease."

Bell said this may be because when vaccines were first rolled out, the focus was on the elderly because of their high risk of dying from COVID-19.

"Unfortunately, it sort of backfired in that people now think kids don't get COVID or aren't going to get sick from COVID or won't die from COVID," she said. "And that's not true. It's certainly not at the same rate … but it's still a possibility."

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics and Children’s Hospital Association report, as of May 26, 2022, nearly 13.4 million children have tested positive for COVID-19, almost 40,000 have been hospitalized, and over 1,000 children have died since the onset of the pandemic.

Dr. Richard Malley, a senior physician in pediatrics in the division of infectious diseases at Boston Children's Hospital, added that booster shots are not easing the fears of hesitant parents.

"The hesitant parents are not going to become less hesitant because now we're saying, 'Oh, by the way, it's not a two-dose series, it's a three-dose series,'" he told ABC News. "Unfortunately, it makes people, in general, a little less inclined because they are like, 'Do I really have to sign my child up to get vaccinated every five months?'"

The importance of booster shots

Malley and others think people have interpreted the rollout of boosters as a sign the vaccines are not effective.

Several studies, however, have shown that while immunity does wane, the vaccines are very effective at preventing severe disease, hospitalization and death, and this is true in children who have been vaccinated.

"What we really want out of vaccines for respiratory viruses is to keep people out of the hospital,"Bajaj said. "And if we can reframe it as, 'Yes, your child still may get COVID, but the vaccine protects them from getting severely ill,' I think we may have a better chance of really trying to help folks feel more comfortable with it."