New FDA labels include nutrition info for eating that whole bag of chips or pint of ice cream

The label changes are designed to reflect how Americans actually eat.

On Jan. 1, the Food and Drug Administration's new nutrition labeling rules kick in, ushering in a host of changes to the way that manufacturers are required to label packaged foods.

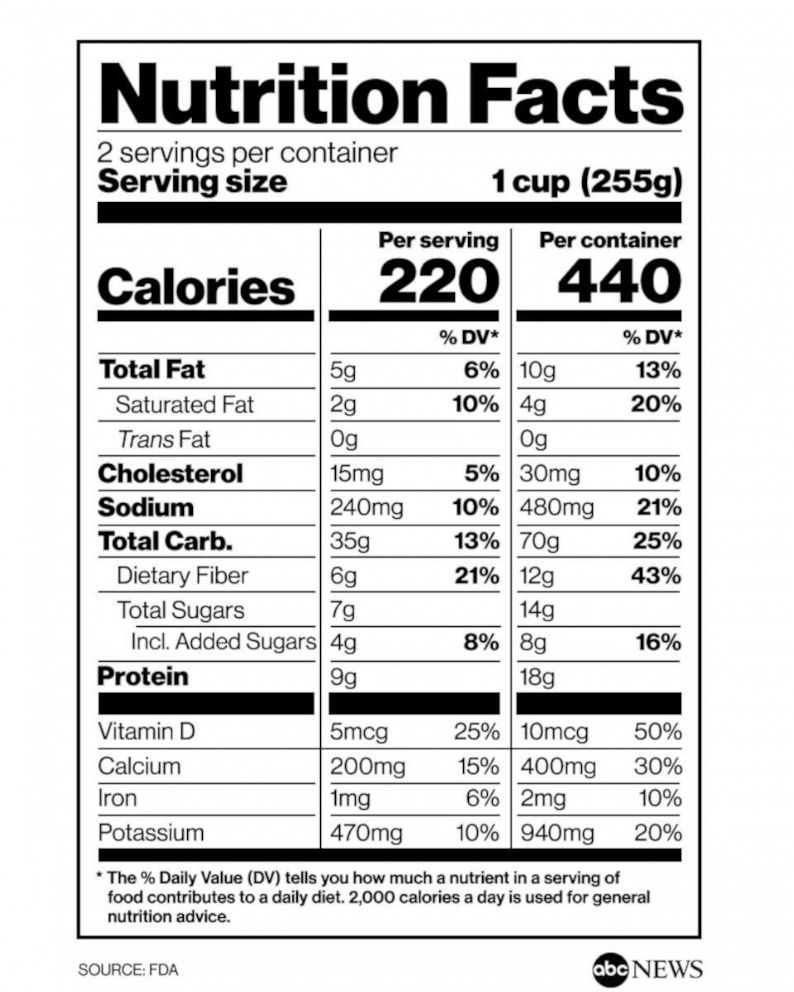

Perhaps most notably, new guidelines require two side-by-side columns: one with nutritional information for a single serving, and a second with information for eating the entire package.

Manufacturers that yield less than $10 million in annual food sales will have until 2021 to comply with the new rules.

"We know that Americans are eating differently, and the amount of calories and nutrients on the label is required to reflect what people actually eat and drink," Claudine Kavanaugh, director of nutrition and food labeling in the FDA's Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, said in a statement.

While consumers might not notice a huge change at first glance, Beth Kitchin, an assistant professor in the University of Alabama at Birmingham's department of nutrition sciences, appreciated the enlarged and emboldened calorie information on the new labels, as well as the new emphasis on serving size.

Serving sizes are based on Americans' eating habits, determined by the amount people said they consumed in federal food surveys over the past few decades.

With foods that can reasonably be consumed in one sitting, like a pint of ice cream, "the serving size is not what you think it is," Kitchin said. "It's a really good change because so many times I've talked with consumers who were deceived by that."

Dr. Frank Hu, a professor of nutrition and epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, called the new label changes an "important step forward."

He pointed to the fact that manufacturers are now required to disclose added sugars on labels.

"Because higher added sugar intake has been associated with a wide range of adverse health consequences, it is important to distinguish added sugars from natural sugars in a product," Hu said.

Consuming too much added sugar has been linked to weight gain, obesity, type 2 diabetes and heart disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Differentiating between naturally occurring and added sugar could also clear up confusion among Americans who think that all sugar is bad for them.

Kitchin said that Americans who are trying to lower their sugar intake sometimes eschew foods like milk, which has naturally occurring sugar, and miss out on nutrients along the way.

"In people's overexuberance to decrease sugars, they may be decreasing some healthy foods," she said.

In general, Kitchin hopes the changes will encourage customers to take more interest in reading nutrition labels and prompt them to compare foods' nutritional information before they buy.

"Hopefully, the information on the new label will not only help consumers make more informed decisions about their food and beverage choices, but also motivate food manufacturers to improve nutritional quality of their products," Hu added.