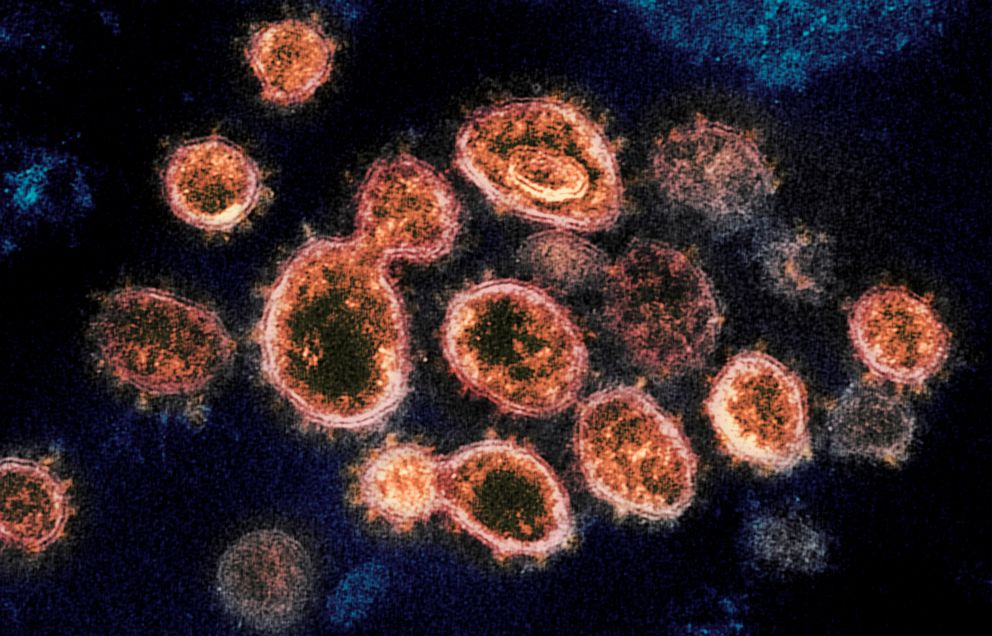

Scientists studying COVID-19 variants to determine effect on vaccines

Early studies show vaccines are less effective against a South African variant.

Around the globe, scientists are studying new and more contagious COVID-19 variants, and their potential impact on vaccines.

"It's not a surprise that we're seeing variants -- viruses do change over time," said Dan Barouch, director of the Center for Virology and Vaccine Research at Beth Israel Medical Center in Boston.

Scientists call them "variants of concern," and say there are three noteworthy ones. As of Thursday, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed that all three variants have been detected in the U.S., and scientists are racing to understand their impact on vaccines.

Studies show that the currently authorized vaccines could protect against one of these variants currently plaguing the United Kingdom. However, preliminary laboratory studies indicate that the South African variant is chipping away at the 95% level of efficacy seen in both the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines.

"That [variant] actually looks like it's got lower protection from vaccines, and in particular about six-fold lower to our vaccine," Moderna President Stephen Hoge told ABC News. Novavax, another vaccine developer, announced that its candidate also appears to be less effective against this particular variant in real-world studies.

"But nevertheless, different developers are taking these very seriously and are thinking about ways to potentially update vaccines with the new sequences," said Barouch.

'We're calling it a strain-specific booster'

Moderna and Pfizer are now planning a step ahead, announcing they will tweak their vaccines, with Moderna announcing a "booster shot" made for specific COVID-19 variants.

"For now, we're calling it a strain-specific booster, because that's what it is, or a variant-specific booster," said Hoge. "Our platform technology allows us to move very quickly and do these sorts of rapid, almost copy and paste, adaptations of our vaccine."

Both the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines use mNRA technology, which relies on the genetic code of the virus -- meaning they can be updated without starting from scratch.

"MNRA is essentially a message -- that's actually what the M stands for," said Angela Rasmussen, virologist at Georgetown Center for Global Health Science and Security. "It's a set of instructions for your cells to make a protein."

Changing those instructions create "a very similar vaccine just with a very slight modification," according to Barouch.

'Likely won't need a booster shot every year'

Scientists are optimistic about the future, saying that as the virus evolves vaccines can be changed quickly to address new mutations.

"There's no limit to the number of changes that can be made," said Barouch, adding that these boosters could take some months to develop. "It does require some time to modify the vaccine and then to test it in at least a small number of individuals."

However, the virus likely won't mutate quicker than vaccines can keep up.

"Fortunately, [COVID-19] doesn't evolve as quickly as influenza," said Rasmussen. "It's unlikely that we would be getting a new booster shot every year, the same way we do with influenza shots."

AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson expecting data soon

AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson are still testing their vaccine candidates, but both companies say they are also ready to update their vaccines with relative ease.

"AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson, which we are expecting clinical trial data from any day now, are not mNRA vaccines, they're viral vector vaccines," said Rasmussen. "So it's also a fairly simple process to change those vaccines as well, if you needed to reformulate them to account for any new variants."

Barouch is one of the lead scientists developing the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, adding that the platform they chose could be updated -- similar to Moderna and Pfizer.

"The J&J vaccine uses a common cold virus, called an adenovirus, that has been deactivated so it can't cause disease in humans," said Barouch. "The goal is to essentially shuttle the COVID-19 spike protein DNA into cells; now that system is actually very amenable to modification."

All the scientists who spoke with ABC News emphasized that the current vaccines still work, and urged all Americans should get vaccinated as soon as possible. The sooner the country reaches herd immunity the less likely it is that the virus will continue to mutate and evolve.

"Viruses can't mutate further if they can't replicate," said Rasmussen. "So if we are taking vaccines, if we are getting community transmission down, that's going to give the virus less of an opportunity to continue to evolve."

This report was featured in the Friday, Jan. 29, 2021, episode of “Start Here,” ABC News’ daily news podcast.

"Start Here" offers a straightforward look at the day's top stories in 20 minutes. Listen for free every weekday on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, the ABC News app or wherever you get your podcasts.