Need a New Year's exercise resolution? Here’s what the latest science says is optimal for health

Advice from experts on a fitness formula for 2020 and beyond.

If you're looking to get back on the fitness wagon after a holiday season of overindulgence, consider making this year's goal to exercise for optimal health, rather than weight loss.

But what does that actually look like? ABC News spoke with cardiologists, physicians, sports medicine experts and researchers to try to pin down an exercise formula for boosting your health in 2020 and beyond.

Even the tiniest bit of exercise is health protective

With the caveat that optimal physical activity is not "one size fits all," since people's optimum levels are tied to factors like age and disease status, experts agreed that if you're sedentary, the most important way you can improve your health is to just get moving.

For people who can't perform the minimum level of recommended activity (around 150 minutes a week of moderate activity), even adding 10 minutes of walking per day to their daily routine "can markedly improve health," according to Steven Moore, an investigator at the National Cancer Institute.

While that might seem like a low bar, the reality is that 1 in 4 older adults do not engage in any regular physical activity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

"The biggest benefit in terms of mortality is that transition from a sedentary to an active lifestyle," said Dr. Benjamin Levine, who directs the Institute for Exercise and Environmental Medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas.

"People who are completely sedentary and do no regular physical activity get a huge benefit simply from going from sedentary to active," Levine said.

A prescription for health

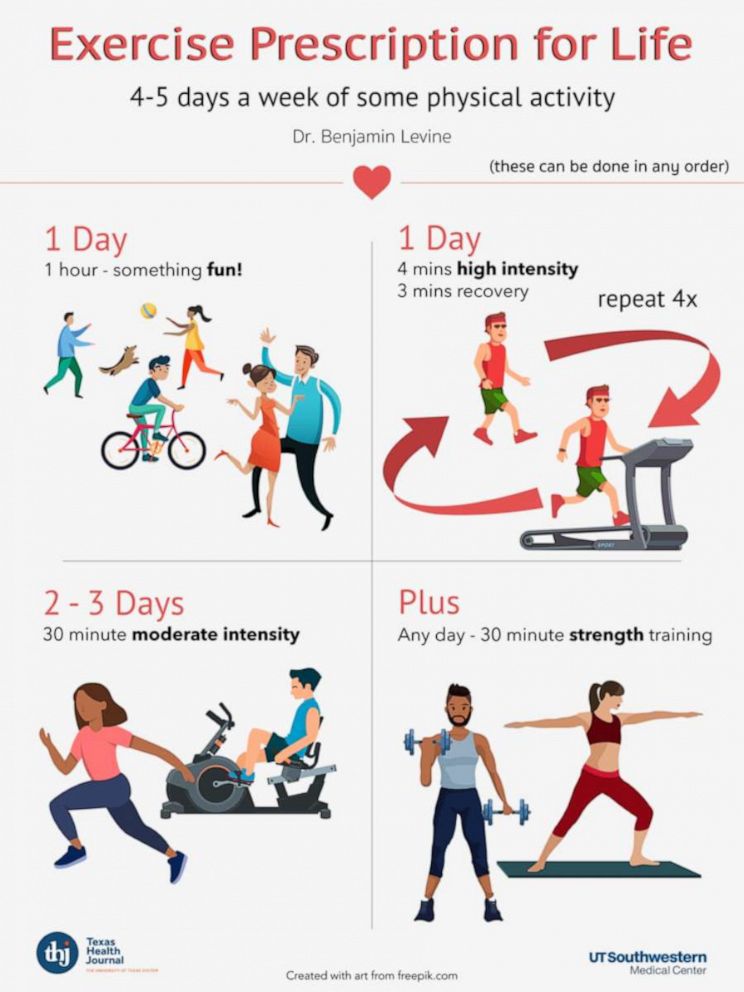

If you're already leading an active lifestyle, but want to optimize your efforts, Levine has designed what he calls a "prescription for life."

Levine's prescription is a twist on the federal guidelines for health, which recommend getting between 150 and 300 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise, or between 75 and 150 minutes of high-intensity aerobic exercise each week, in order to maintain a healthy body.

His recommendations are based on data that followed individuals over decades, and analyzed how much exercise they had to do for maximum cardiovascular, fitness and mortality benefits, he said.

The breakdown: Four to five days of exercise per week, including one day of high-intensity exercise; two to three days of moderate-intensity exercise; one day of strength training; and a fun active day.

High intensity: The high-intensity workout should be something that you can't sustain for very long, such as high-intensity interval training, which is when you exercise to the point of fatigue in short bursts, punctuated by short periods of rest.

Moderate intensity: Moderate-intensity workouts could include riding a bike, using a rowing machine or elliptical or just going for a walk, as long as that activity makes you a bit short of breath, Levine says. Not sure if your workout is in the moderate-intensity range? Try the talk check. "You can talk. You're short of breath, but you definitely can't sing," he explained.

Strength training: Think outside the box when it comes to strength training. "Strength training doesn't have to be with dumbbells or a weight machine," Levine said. "It could be Pilates, it could be a strength type of yoga, it could be a CrossFit-type workout." Mix and match to find something that works best for you.

Long, slow activity: This could be playing tennis, going square-dancing or taking a long walk, as long as the activity lasts for at least an hour. "I try to avoid the things that get people to stop exercising, which are injuries and pain," Levine said. You're also more likely to stick with a fitness routine if you're doing an activity you enjoy.

That four- to five-day regimen will put you in the 3 to 5 hours of health-protective exercise per week range, which is about where mortality benefits tend to top out, according to Levine.

For other health outcomes, like preventing heart failure, there doesn't seem to be an upper level of exercise benefit. "The more you do, the better you're protected," he said.

An alternative method: Gradually increasing your step count

If exercising five days a week seems daunting, it's OK to start small.

Dr. William Kraus, who served on the committee that set the physical activity guidelines for the Department of Health and Human Services in 2018, stressed the importance of an active lifestyle for health.

"If you're inactive, get out and start moving around," Kraus said. "Anything is better than nothing."

One trick to try: Increase your step count gradually, taking an extra 2,000 steps each day, until you hit 13,000 steps, which works out to walking between 4 and 5 miles per day.

Once you reach 13,000 steps, you can hold steady.

"The consensus is that the [adding] 2,000 steps goal is a reasonable thing to strive for," Kraus said.

Consistency is key

Throw away your weekend warrior mentally, advises Erica Woekel, clinical assistant professor and director of the lifetime fitness for health program at Oregon State University.

It's better to get your heart rate up a few times a week than to go all out one weekend a month, potentially injuring yourself in the process.

"Consistency is always going to be the better thing to strive for," Woekel said. "Sometimes we don't see an impact, health-wise, until we've been doing it consistently," she added.

The key, she emphasized, is finding an activity you enjoy, whatever that looks like, and making it a regular and necessary routine.

Levine seconded that advice.

"At the end of the day, it has to be something that you do as your personal hygiene, just like eating, showering or brushing your teeth," he said.

"It can't be something that you just add on at the end of the day," he said. "Because that's hard to sustain."

One you're in the swing of thing, mix up your routine to avoid injuries

Having a multifaceted exercise program, which includes aerobic activities, flexibility, balance and strength training, is crucial for avoiding injuries that can derail an active lifestyle altogether, according to Dr. Laura DeFina, president of the Cooper Institute preventative medicine and public health research group.

That variety may be especially important for older women, according to Dr. Elizabeth Joy of Intermountain Healthcare, and a past president of the American College of Sports Medicine.

"Women in middle age and older need to engage in strength training to a greater extent than men, because they are at risk for age- and inactivity-related muscle loss," Joy said.

Important as it is, Joy acknowledged that starting a weight-lifting or yoga regimen can be intimidating to people in their 50s, 60s or 70s if they've never done it before.

"At a time in their life when they need it the most is when they feel least confident in engaging in it," she said.