Auschwitz survivors return for 75th anniversary of camp's liberation: Going back tells the dead 'I remember you. … I mourn you'

Now in their late 70, 80s and 90s, they shared their memories with ABC News.

They were all younger than 18 when -- packed into cattle cars -- they arrived in Auschwitz, a place they had never heard of, but that would stay within their memories forever.

Irene Weiss was 13 when she was taken with her family on that cattle train ride.

"The Jews had long before been taken to Auschwitz. And we had never even heard of the name Auschwitz. We had no idea there was such a place," Weiss told ABC News. "My father was looking out that little window at the top of the cattle train ... we fully expected, then, the train would stop, [and] a firing squad would be waiting for us."

Instantly separated from their families, they witnessed whole families being murdered, including their own.

"I was in front. And my brother was in front of me as a boy. And they all went to the right and they sent me to the left," David Marks, who was 16 when he arrived in the Birkenau section of the camp, told ABC News. "It was shocking that all of a sudden, you see that you are alone and just before, you were with your parents."

They survived other horrendous atrocities before the Nazis forced prisoners on a death march as Russian forces approached the camp -- months and years after their arrival.

When the Red Army closed in on the camp, Tova Friedman's mother told her to hide among the dead in a camp infirmary. She lay still under a blanket as she listened to the Nazis attempt to kill the remaining prisoners. Friedman wasn't even 6 years old when she arrived to the camp.

The Russians liberated Auschwitz on Jan. 27, 1945. But by then, more than 1.1 million people -- nearly a million Jews from all over Europe -- had been killed at the camp. Of the 232,000 youth deported to Auschwitz, only about 6,700 were selected for forced labor. Other children managed to survive by hiding, or got lucky not to be sent to instant death. Adolf Hitler and the Nazis were responsible for the slaughter of 6 million Jews across Europe.

Tova Friedman, Weiss, Michael Bornstein, Marks, Lois Flamholz, Peter Somogyi and Claire Heymann were among them.

On Monday, these survivors returned to Poland to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the camp's liberation and remember those who had been persecuted and killed -- including their families and friends.

Now in their late 70, 80s and 90s, they shared their memories of hardship and survival with ABC News' "World News Tonight" anchor David Muir, as they left the homes they'd built in the United States and returned to Poland to send a clear message: never forget.

"I think of all the people who were destroyed, who were massacred, who were gassed," Friedman said. "My going back is my telling them, ‘I remember you. … I mourn you and all the children and all the mothers.’"

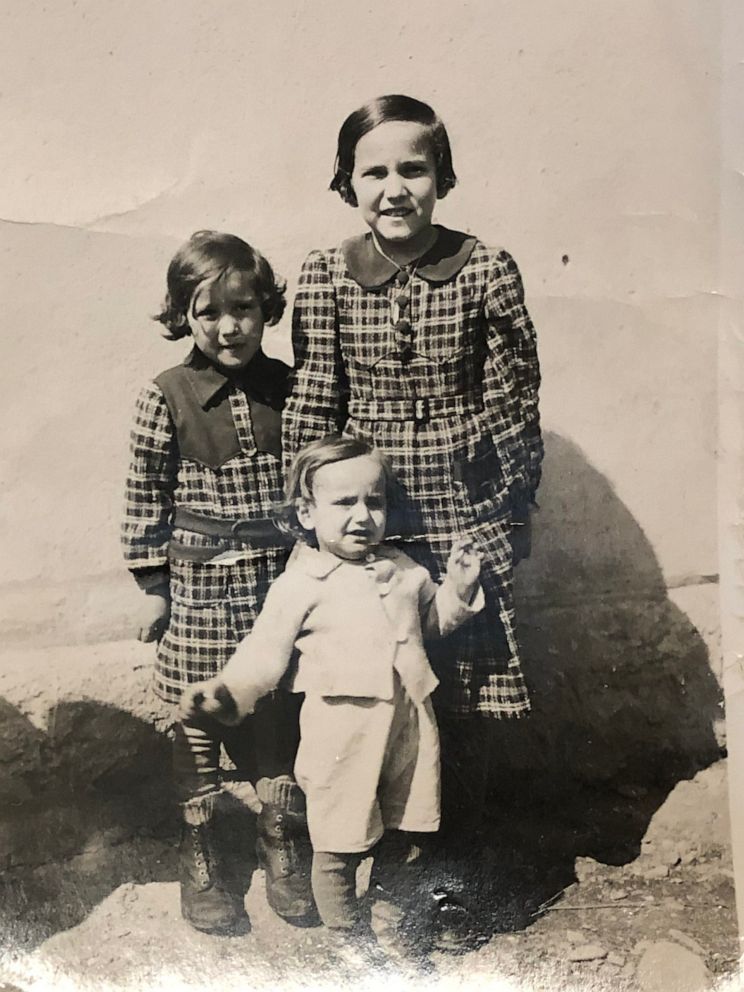

Muir and his team also met recently with Friedman and survivor Bornstein. The two survivors reflected on a photo of them as children after the liberation.

"We're defying Hitler," Friedman told Muir. "We defied Hitler. We won. ... We remember those that died and we live a good life. We thrive here -- not only survive."

Tova Friedman

Tova Friedman said she credits her survival on her mother, who opted to never lie to her about the Holocaust and what the Nazis were doing to the Jewish people.

"(My mother) also helped save my mind, not only my life, my mind. Because when she spoke to me ... when she explained what was going on, I understood it. At the age of 4 and 5 ... I didn't know what death was but I sort of knew that you don't come back from whatever death is. ... My mind wasn't as panicked as it could have been," she said.

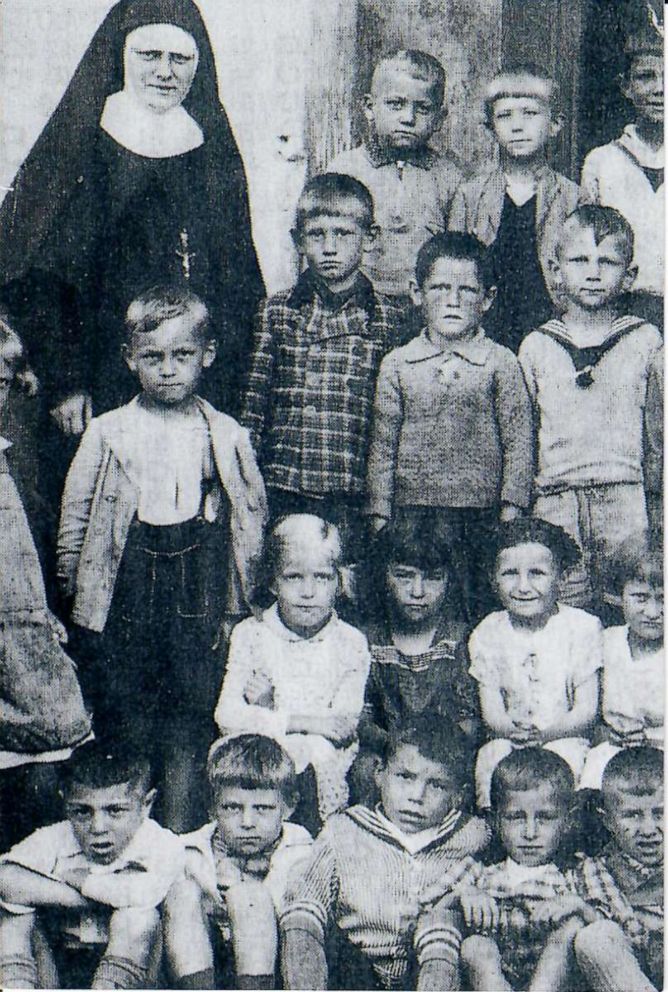

Friedman's family was forced to move to a ghetto with other Jewish families, later ending up in a labor camp, where her parents hid her in a crawlspace at their home to prevent her from being taken away by the Nazis with other children. From there, she'd see the children from her town separated from their parents and shipped to certain death.

"Every time they moved you to a new place, they would clean up the old place so that nobody could say, ‘Look what you’re doing!’ In fact, at one time, when the Red Cross came to another place, everything was cleaned up," she said.

We won. ... We remember those that died and we live a good life. We thrive here -- not only survive.

But as the persecution of Jews accelerated, Friedman and her parents were taken to Auschwitz in a cattle car train.

"You couldn’t lie down. You slept standing," she said. "(My mother) just had her hand around me. … The noise was impossible, the screaming of the people, crying."

When they arrived at Auschwitz, she was told to undress and her hair was cut, as she said she watched women being taken to the crematorium. Later, she was tattooed and sent to a children's barracks. Her new name: 27633 A. She was 5 and a half years old.

She turned 6 at the camp, and recalled realizing it was her birthday when her mother smuggled a piece of bread. The little packet read: "Happy sixth birthday."

The gift came at a cost though -- her mother was severely beaten and Friedman never got to eat that bread.

"I went to the crematorium. ... I knew that I was going. You know why? Because the barrack next to me had gone a few days earlier. I didn't know where they were really going, but it was empty. The barrack was empty. And this, and we were one of the last barracks left," she told Muir.

Her mother, from whom she'd been separated, saw her.

"I hear my name. And I said to myself, 'Who knows my name? This is my name. Must be my mother.' So I hear a voice. I didn't even recognize the voice, but I hear somebody say, 'Where are you going?' And I said, 'To the crematorium.' And they started screaming. And I remember turning to the little girl next to me and I said, 'Why are they screaming? Every Jewish child goes there, so now we're going there,'" Friedman said. "I was a year old when the war broke out. I didn't know anything else."

After getting undressed, she waited but the shower she had been told about never came.

"Hours later, they told us to get dressed," Friedman said. "Coming back was freezing. It was so cold. And I hear my mother's voice again, my name. She says, 'What happened?' And I remember saying it in a very loud voice, 'They couldn't do it this time. They'll do it next time.'"

As the Russians closed in on Auschwitz, Friedman remembered, her mother chose to hide and possibly die instead of joining the Nazi march. The two hid among the dead in the women’s hospital.

"I don’t know how long it took but I heard Germans coming in. … They were running away but they were shooting people who were almost dying anyhow. … I always heard those German boots. Sometimes I have nightmares about those boots," she said.

She waited among the dead, under a blanket, until her mother returned for her. In the meantime, the Germans took tens of thousands of Jewish people with them on a death march to other camps.

"They're gone," she said her mother told her.

Later, the Russians arrived. Friedman, now 81, said she has celebrated Jan. 27, 1945 as her second birthday ever since. Out of the 5,000 children in her town, she said, she was one of five to survive.

In a film recorded by the Russians days after the liberation, children including Friedman and Bornstein, can be seen pulling up their sleeves to reveal the numbers the Nazis had tattooed on them. They showed Muir that image, now in the Museum of Jewish Heritage: A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, in New York City.

"They were telling us, they gave us, like, an order to 'Show us the number. Show us so we could show the world,'" Friedman said. "They liberated us and then they fed us. And, we got some clothing. And, we could sleep in -- regular sleep without fear. And, a week later... they took this picture."

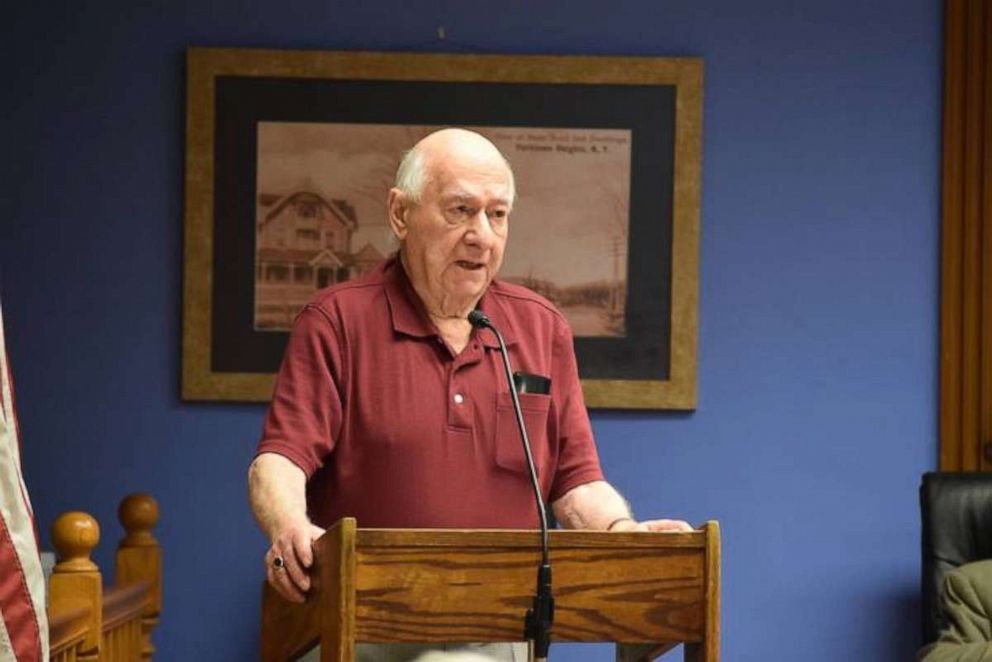

Michael Bornstein

Michael Bornstein, 79, was living in Zarki, Poland, with his family when the Germans arrived in Sept. 1, 1939. His father was selected to be the president of Judarate, a group of people chosen to be the go-between for the Jewish people and the Nazis.

As anti-Semitism and violence escalated, and fearing deportation, his parents buried a safe behind his house to hide their jewels, money and other personal belongings. By July 1944 that fear materialized, he and his family were transported by train to Auschwitz after being forced to work in labor camps.

"I do remember going into the packed train. I can tell you, it was very difficult to breathe. In fact, one of my grandparents suffocated in one of those rides to a concentration camp. … I go on New York City subways and sometimes, crowded subways, and I think about that cattle car ride to Auschwitz," he told Muir.

At Auschwitz, his family was split up: His older brother and father went to the men’s camp; his mother and grandmother to another side. Bornstein, 4, was sent to the children’s barrack. He later learned that his father and brother had been killed. His mother was devastated, but was determined to protect Bornstein. She hid him in the women’s bunk while she was forced to work and snuck him some of her bread so that he would not starve.

All the while, she kept telling him: "This too shall pass."

The Nazis tattooed him with the number: B-1148. Her mother was eventually sent to work at a factory in Austria -- and Bornstein was left with his grandmother.

As the Russians were closing in on the camp, and the Nazis forced everyone to go on a death march, Bornstein and his grandmother stayed behind in an infirmary because he was ill. They remained there until the Russians arrived and freed them.

Of the hundreds of thousands of children who were brought by train to Auschwitz, Bornstein said, only 52 younger than the age of 8 made it out alive.

"It was just unbelievable," he said. "The normal lifespan of a child my age was about two weeks. And, I managed to survive in Auschwitz for about seven months."

Returning back to his hometown proved difficult. His home was now occupied by a Polish family, forcing his grandmother and him to live in a chicken coop. His mother, with whom he reunited after a chance encounter in town, snuck back into their old home to find the safe she'd hidden, but it was gone.

Only a Kiddush cup was left.

Years after liberation, and in the United States, his mother would save money from odd jobs to gift him a watch. Later on she inscribed in it those words she always repeated: "This too shall pass."

Bornstein planned to take that watch, and the cup, back to Auschwitz.

David Marks

David Marks was born in Hungary in a small town to a small family with 12 siblings. When Hungary joined the Nazis, he was not allowed to attend school after sixth grade so he worked as a laborer. He said the owner of the shop was terrified that the authorities would learn that he was employing a Jewish youth and teaching him a trade.

"He told me when somebody comes, I should take right away a broom and sweep up and I shouldn’t hold even a hammer in my hand," Marks said. "Of course, I was very happy to it and I was working 12 hours a day."

Marks worked in the shop for two years until the Nazis forced the Jewish people to move to the ghetto.

The normal lifespan of a child my age was about two weeks. And, I managed to survive in Auschwitz for about seven months.

"We were in the ghetto about four weeks without food, without bedding. And from the ghetto, they took us into a little field and they took away from (us) all our documents, money, everything and (threw) it away," he said.

Marks and his extended family of 35 as well as other Jewish people were put into cattle cars.

"They put in two pails. No food. Nothing. Old people, the young people. … We are all in the train. The train was going about three, four days till we got to the border between Poland and Hungary," he said. "The next day, we were already in Auschwitz."

He was 16 when he arrived to the camp.

He never saw his parents, or most of his relatives again. Some close family members were killed that first afternoon at Auschwitz.

"I was maybe 10 blocks from the crematorium and we had no idea what they’re burning there," he said. "We were told that they’re burning waste, garbage because we saw the big building and smoke but we had no idea. No idea."

He was put in a barrack filled with 1,500 children. When scarlet fever broke out, he said, the ill children were killed. Fearing that they too would get sick, he and some friends escaped the barracks through a roof and hid from the soldiers for two days, but eventually returned.

He said at some point, Nazi physician Josef Mengele entered the barracks and checked to see whether he and his friends could work.

"He said, ‘If I will hit you in the face and you don’t fall over, then you’ll be able to go to work.' So, I didn't know what side he's gonna give it to me. So, I spread my leg a little bit so I should have resistance," Marks said.

Marks was struck repeatedly but he took the hits and was able to work.

"There was a kitchen and they needed 15 children to peel potatoes and volunteer. So, of course, I volunteered because at least you could have raw potatoes," he said.

After learning that some of his sisters were alive and on the other side of the camp, he even swapped potatoes for bread and shoes that he was able to get to his sisters on the other side of a fence in the camp. He spent three months in Birkenau, he said.

"We never thought that we’ll be able to escape from there," he said about himself and a friend. "You had no time to think of anything. You didn’t have time to plan to escape because there was no chance."

Marks said he and the others were not aware that the Russians and liberation was near. The prisoners were told to stop building a huge factory they'd been working on and start marching to a huge camp -- Dachau.

"We were so weak that we just didn’t know how this is gonna end and what are you going to do with us," he said.

When the Americans arrived to the camp, the Germans either surrendered or killed themselves. He said that he and the others didn't have the strength to rejoice in their freedom.

Irene Weiss

Irene Weiss was 13 years old and living in Hungary with her family when they were sent to Auschwitz in the spring of 1944.

"They opened the train from the cattle car from the outside, and then they were yelling orders. First order is to leave thing behind and get out. And they kept repeating that, and with great urgency. 'Don't take anything. Leave everything behind and get out,'" she told ABC News.

At the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., where she now volunteers, there's a photograph of the day she arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau, right after she was separated from her 12-year-old sister, Edith, who was taken to the gas chambers.

Irene, though only a year older, had been selected for forced labor, she said, likely because she was wearing a kerchief on her head that made her looked much older.

Separated from her younger siblings and her parents, she caught up with another sister, Serena, who was three years older.

"Suddenly that whole idea that there'll be reunions, that whole thing suddenly flashed in front of me, and realized that-- that is not the way it is here," she said. "I suddenly realized that something very terrible happened to our family."

We never thought that we’ll be able to escape from there.

Eventually, she would also find two of her aunts, and the group was sent to work sorting through the belongings confiscated from the newly arrived prisoners.

"Just an electrified fence-- dividing us from-- crematorium and gas chamber number four. And we had the unfortunate experience to see groups of women, children, and elderly getting off the train, and entering the gate into that gas chamber," she said. "We suddenly realized what was happening. No one had to tell us anymore what-- what they were up to. Within a half-hour or so after … chimneys were belching fire and smoke,"

Her entire family was killed except her sister Serena and two aunts. Weiss was tattooed with the number A-6236.

When Weiss was sent on the death march in January 1945, the Nazis sought to put their Jewish prisoners into concentration camps deeper in Germany. Weiss spent five months in these camps with no food. Typhus broke out. She was waiting to be sent to the gas chambers when the Russian troops arrived and the Germans evacuated the camps. She said that even after the Russians liberated the camp, the soldiers did not help the prisoners, fearing being contaminated with typhus.

She said she had to hitchhike with her sister and a very sick aunt from village to village in hopes of finding a hospital. Thankfully, her aunt did survive.

She told Muir that she'd had the tattooed number removed but still has a scar.

"I couldn’t deal with the questions (about the tattoo)," she said. "It was one of those things that I could not answer. … You just don’t throw out answers about Auschwitz, just like that."

Weiss, 89, said the journey on Monday would be her third trip back to Auschwitz.

Lois Flamholz

Lois Flamholz and her family were living in a small town in the Carpathian Mountains, which became a part of Hungary in 1939. When the Germans arrived, her family was told to pack up their belongings and move to a Jewish ghetto.

In the ghetto, she said, they were all put in cattle cars on a train and taken to Auschwitz. She was 16.

"They told us to strip naked, throw all -- everything on a pile, the shoes on one pile, the clothes in another pile. And that's when we had to stand naked. They shaved us from head to toe," she said. "The soldiers standing there and watching."

She and several cousins were separated from her mother, father, grandmother, aunt and siblings immediately when they arrived. She said she never saw her family again. She and other girls were put in barracks, where they cried and asked the women when they would see their mothers again.

"She says, 'Oh, you wanna see your mothers? You see the smoke over there? That's where your mothers are.' And that's when we found out about the crematoriums. 'Cause we were very close by the crematoriums," said Flamholz, 92.

She stayed in a work camp till February 1945, when they were told to march. They marched for about six weeks.

"I was so sick. It got to a point that, when we had to stand on line… that two other people from the other two lines had to hold me up, in order to stand up," she said. "I refused to go to the infirmary… I said to my cousin, ‘If I go to the infirmary, I’m not gonna come out.’"

Her group was liberated by the English in Bergen-Belsen. While she was in the hospital with other girls, a cousin fell very sick. Flamholz said she tried to give her cousin a sip of water and pleaded with her to stay alive.

"I picked her up, sort of," she said. "I didn’t realize that she was dead. I was trying to tell her, ‘The war just ended.’ … I says, ‘Please, hold on.’ And she was dead."

Flamholz told ABC News that it took her many years to be ready to talk about what had happened to her during the Holocaust.

"When my children were little, they only asked me once, ‘How come their friends have grandparents and they don’t?’ So I started crying. … I couldn’t talk to anybody about anything. I just couldn’t even think of what I went through," she said.

She said her children and grandchildren were what kept her alive and going.

"I said, ‘Hitler destroyed my whole family. He tried to kill me also. He is dead and I built a beautiful family that I’ve very proud of.’ And, that’s it. That’s my life," Flamholz said.

Claire Heymann

Claire Heymann was 18 when she was brought to Auschwitz. Her father had been sent to a camp before, as had been two of her sisters and a bother. All of them were killed.

Heymann was sent to work in a factory with other young women but eventually was sent to Auschwitz with a third sister.

She spent two years in the camp and was tattooed, yet, she said, she never gave up hope.

"The worst part was ... when you see people running to the electric fence. ... How many times you see people get caught on the fence and get electrocuted. … They were tired (of) being in Auschwitz," she said.

On the day that the camp was about to be liberated, everyone tried to get food before the death march.

"We walked day and night in snow and ice. ... No more clothes. So we took the clothes off from dead people who are killed. ... We used to eat snow, having no more water. The snow gave us water," she said. "We marched two and a half days."

She and seven girls finally reached a town the Russians were occupying in Germany. She told ABC News that there were "many times" she thought she would not survive while in Auschwitz.

"But every times… I had the willpower. I had a lot of willpower. I said, ‘We have to survive to tell the world what’s going on. We have to do that. Otherwise, nobody would believe us.’"

Peter Somogyi

Peter Somogyi and his twin brother were 11 years old when they arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau in July 1944.

The two were living in Pecs, Hungary, with his father, mother and sister when the Germans took control in March 1944. He said immediately the Jewish people were forced to wear yellow stars and his father was taken away. He and his family lived in a ghetto for about two months before being sent to Auschwitz.

"They loaded us 70 to 80 in the same cattle car. … Every family got only one bread for the duration. … We had no idea where we are going," he said. "We had no idea what’s happening."

For three days and nights, he and his family traveled with others in the cattle car. When they were released, he said, his mother told him to say he was 9 in hopes they would keep the family together. It didn’t work.

"While we were waiting there to move somewhere, (Nazi doctor) Josef Mengele came around ... asking for twins," he said. "Two German soldiers grabbed us. I didn’t have a chance to say goodbye to my mother. That’s the last time I ever saw her and my sister and my family."

He was also given a number: A17-454. When he asked a man when he'd be able to see his mother, he said the man "pointed to the flames and said, ‘That’s where your mother is.’"

"And that’s when I found out what’s really happening," Somogyi said.

He and his brother endured Mengele’s experiments that included blood draws and repeated measurements of their bodies. He said being a part of Mengele's experiments kept him and his brother alive.

"Otherwise, I would have been in the gas chamber the first moment when we arrived over there," he said.

On Jan. 27, 1945, the day Auschwitz was liberated, he and his brother had been lined up with others to begin the death march from Birkenau to Auschwitz. The Germans were shooting anyone who was not able to walk.

They loaded us 70 to 80 in the same cattle car. … Every family got only one bread for the duration.

All of a sudden, he said, the Germans vanished. The Russians had been traveling so fast that the German soldiers just left the prisoners.

"I said to myself, ‘Finally, we are free,’" he said. "You have no idea what kind of feeling (that) is for an 11-year-old kid … Both of us (were) elated that we are free. That’s all that I can tell you."

It took him and his brother two and a half months to reach their hometown after the camp’s liberation. They were later reunited with their father, who had survived the camps as well.

Somogyi, 86, said as he grew up, he learned to put the Holocaust behind him and not dwell on it.

"From the day we liberated and we got home, I never, ever, discussed anything with my brother about it," he said. "We just stopped thinking about it, stopped talking about it. … That was the idea. … Then I came to the realization that, within 10 to 15 years, there will be no eyewitness survivors to tell the story … That’s why I’m telling my story."

"Auschwitz represents the worst of humanity," he said.

Social media:

twitter.com/AuschwitzMuseum

facebook.com/AuschwitzMemorial

Instagram.com/AuschwitzMemorial

Youtube.com/AuschwitzMemorial