How big holes form in Antarctic ice even though it's cold

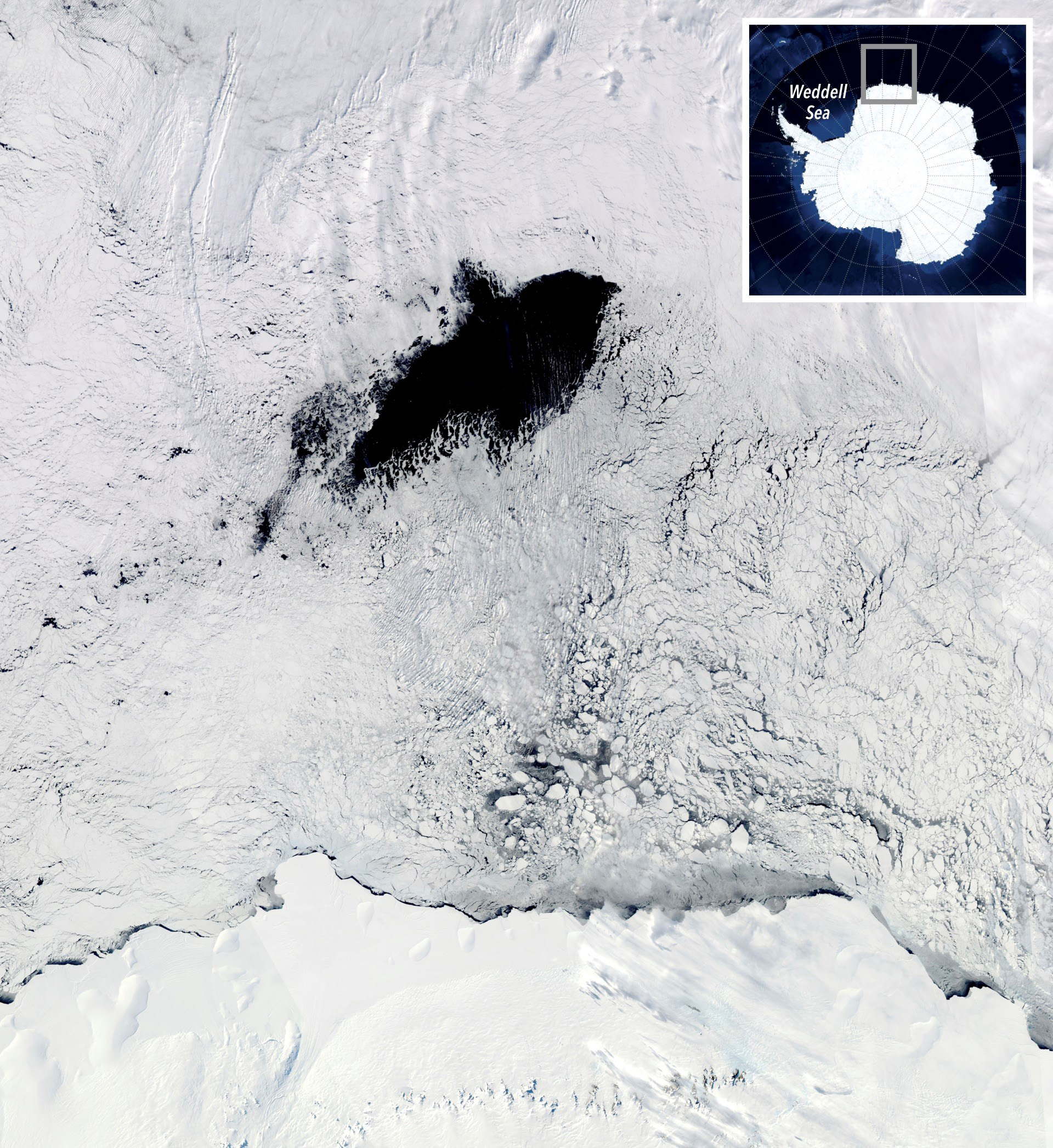

Holes in the ice, known as polynyas, may appear more as climate change advances.

This is an Inside Science story.

(Inside Science) -- By analyzing data from seaborne robots and sensors glued onto seals, researchers may now understand the mysterious origins of giant holes that can open up in Antarctic sea ice, a new study finds.

A polynya -- a Russian word that roughly means "hole in the ice" -- can form off the coast of Antarctica and last for weeks to months, acting as a refuge where penguins, whales and seals can pop up and breathe. The biggest known polynyas in the winter sea ice of Antarctica's Weddell Sea appeared soon after the first satellites were launched, with an area the size of New Zealand remaining ice-free through three consecutive winters from 1974 to 1976, despite air temperatures far below freezing.

The rarity of big polynyas in Antarctic waters meant that little was known about how these holes could form amid the bitter cold. But in 2016, a big polynya emerged for the first time in decades, one 33,000 square kilometers that remained open for three weeks. An even larger 50,000-square-kilometer polynya appeared in September and October of 2017.

Scientists examined decades of satellite images of sea ice cover and data from Antarctic weather stations, and gathered data from robots drifting in Southern Ocean currents and even sensors epoxied onto elephant seals. They found these polynyas formed when the frigid surface water was also especially salty. This salinity made it denser and therefore more likely to mix with similarly salty and dense deeper water.

Intense storms that swirled over the Weddell Sea with almost hurricane-force winds those years churned relatively warm water from the deep ocean upward, melting ice and opening up polynyas in the sea ice. When this water cooled off, it became denser and more likely to sink. Warmer water welled up from below to replace it, creating a circulation of warmth that kept the polynyas open.

"The deep ocean is generally a quiet place where changes happen slowly, but we find that it was stirred vigorously during these relatively brief polynya events," said study lead author Ethan Campbell, a physical oceanographer at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Under climate change, freshwater from melting Antarctic ice sheets would make the Southern Ocean's surface waters less dense, which might lead to fewer polynyas in the future. On the other hand, many climate models suggest the winds circling Antarctica will become stronger and draw closer to its coast, which might encourage more polynyas to form.

The scientists detailed their findings online June 10 in the journal Nature.

Inside Science is an editorially-independent nonprofit print, electronic and video journalism news service owned and operated by the American Institute of Physics.