How China’s Xi Jinping flipped the script on the world during his 10 years in power

“The world has entered a new period of turbulence and change,” Xi has warned.

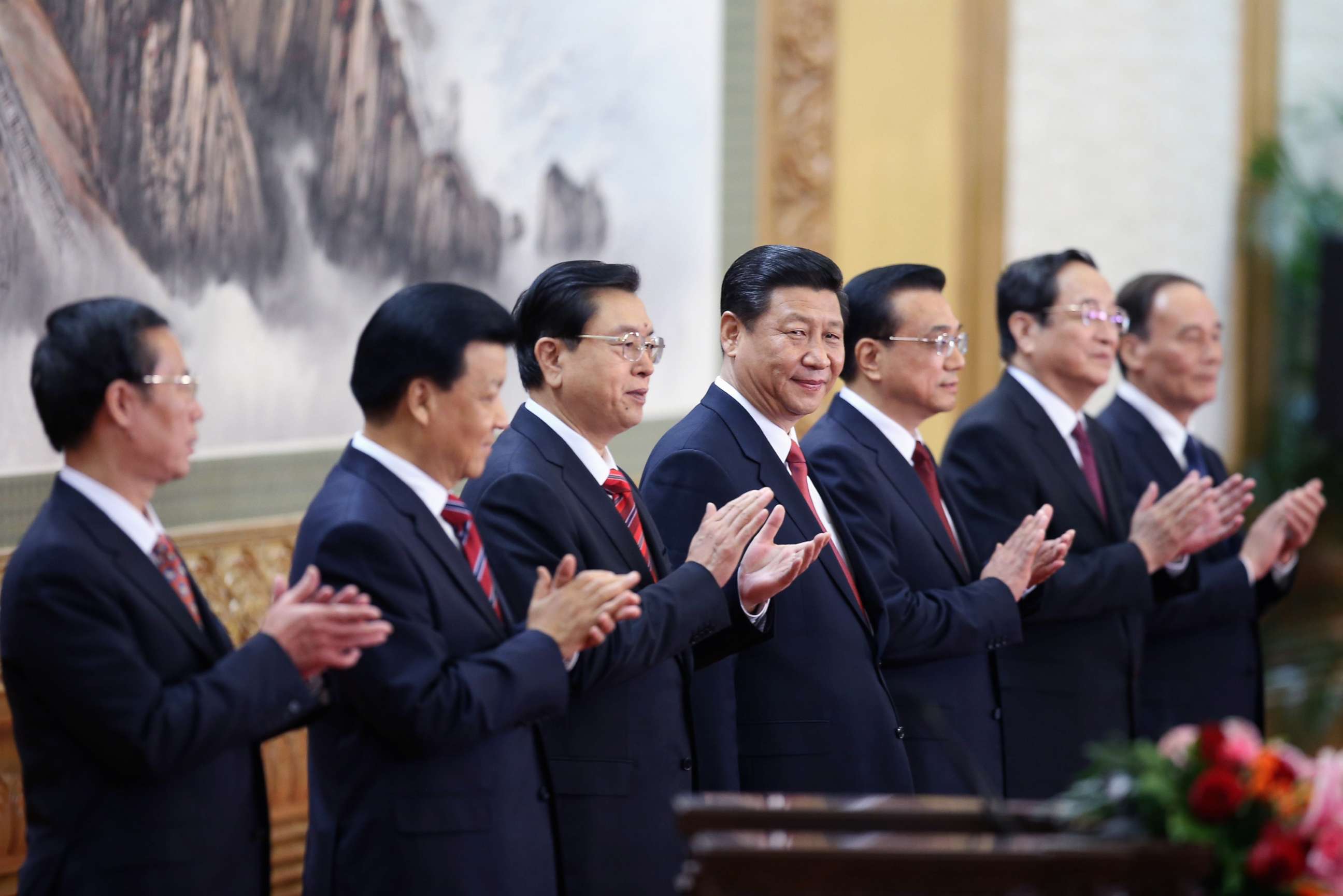

Xi Jinping will stroll across the red-carpeted dais inside Beijing’s gargantuan Great Hall of the People on Sunday, having firmly secured a norm-busting third term as leader of the Chinese Communist Party, cementing his power atop a more confident -- and more defiant -- China.

When he did the same walk 10 years ago, there was a brief sense of hope in the West that China was about to embark on a kinder and gentler age.

“Just as China needs to learn more about the world,” Xi told the gathered press with a modest smile in his first speech as party leader in November 2012, “so does the world need to learn more about China.”

In the lead-up, many sifted through his available biography for clues of what kind of leader he would be. He came of age during the chaotic years of Mao’s Cultural Revolution, rose to govern two of China’s most prosperous coastal provinces as well as the country’s most cosmopolitan city, Shanghai. Xi oversaw the well-received 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics, sent his daughter to study at Harvard and often talked about the fond memories of an Iowa homestay in the 1980s. The son of a revolutionary-turned-liberal reformer, many China-watchers had hoped that the son would be like the father.

This resume led many, like New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof, to boldly predict in January 2013 that “Xi Jinping will spearhead a resurgence of economic reform, and probably some political easing as well. Mao’s body will be hauled out of Tiananmen Square on his watch, and Liu Xiaobo, the Nobel Peace Prize-winning writer, will be released from prison.”

“I may be wrong entirely,” Kristof cautioned.

Ten years on, not only is Mao’s body still comfortably lying in his mausoleum, but Liu was never released from prison until the final months before his death from cancer in 2017.

Meanwhile, Xi’s China has become more confident, powerful and influential than ever before.

Xi brought the Communist Party back to the forefront of daily life in China, linking the party to the country’s growing strength and success, which, in return, has fostered a nationalism that has become inseparable from the party itself. Yet, at the same time, his policies -- most notably his signature zero-COVID policy -- also has also left China more isolated and xenophobic than it has been in generations.

In ten years, Xi has reshaped China

Citing "disorderly capital," Xi has cracked down on private companies, like tech giants Alibaba and Tencent, that powered much of China’s growth in the last 15 years and signaled a desire to return to the heavily self-reliant state-run model.

Instead of political reforms, Xi dismantled China’s nascent civil society, shuttered NGOs and locked up human rights lawyers, stifled religious institutions from Tibetan Buddhism to Christian churches across the country -- perhaps nowhere more prominently than in the western region of Xinjiang where many mosques were dismantled and hundreds of thousands of ethnic Uyghurs have been forcibly re-educated in the name of anti-terrorism.

He muzzled the domestic media, dictating that they must "serve the party," suppressed Hong Kong’s once-promised autonomy and built a high-tech surveillance state that ultimately gave the state the ability implement its zero-COVID measures throughout the pandemic.

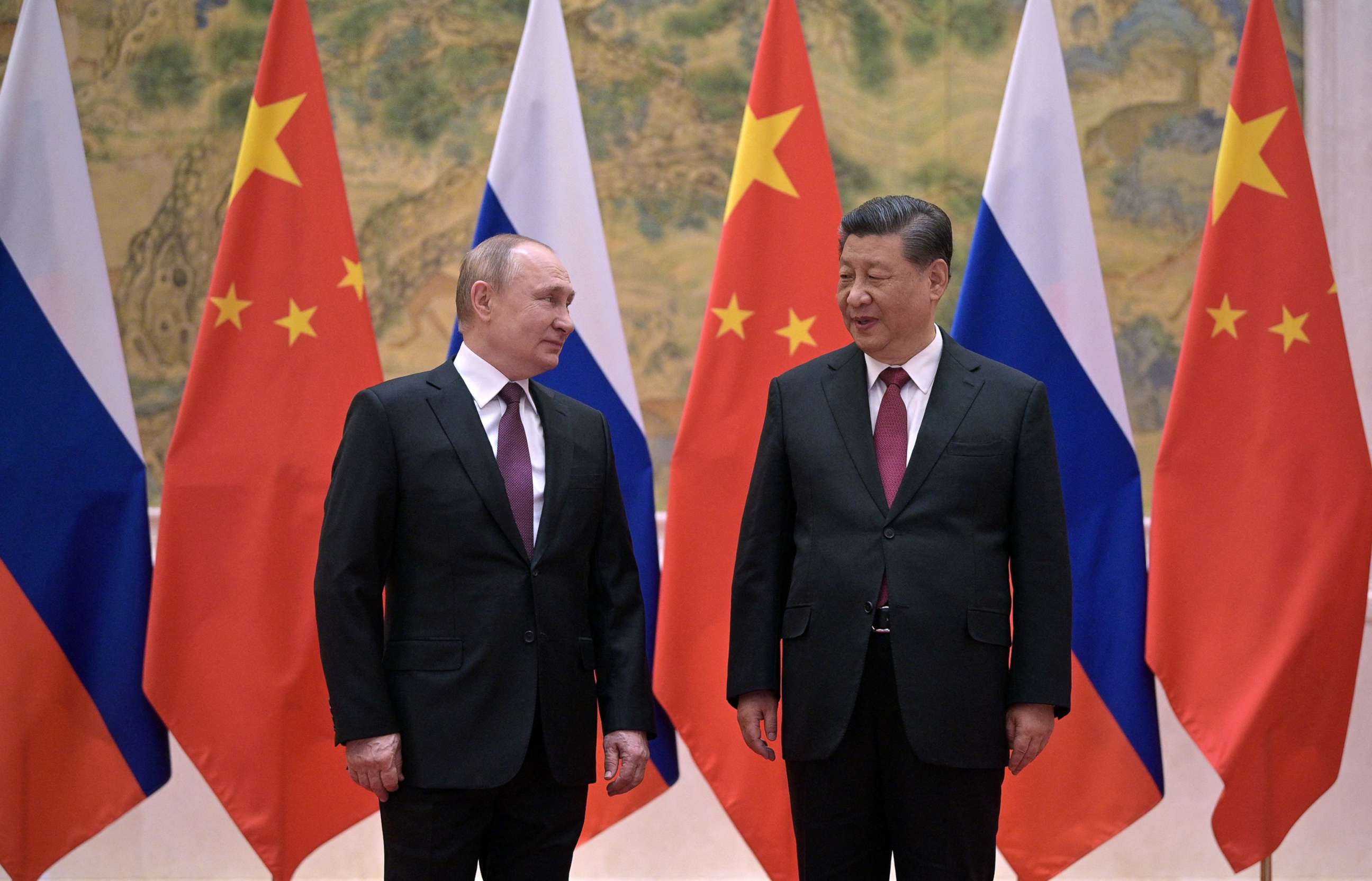

Xi modernized the party’s People’s Liberation Army, encouraged a more strident foreign policy -- especially over territorials claims like Taiwan, the South China Sea and the Himalayas where Chinese soldiers had a deadly tussle with Indian troops in June 2020. He has sought to challenge the U.S.-backed world order by cozying up to Russian President Vladimir Putin whom Xi called in 2018 “my best, most intimate friend.”

It turns out that pre-leadership Xi was not only a cypher to the West, but also worked within the opaque operations of the Party itself.

Deng Yuwen, the former deputy of editor of the Central Party School’s journal, wrote in Foreign Policy magazine this week that, according to party insiders, Xi was selected by party elders believing his low key demeanor would lend to him being more controllable than his rivals. “One can only imagine their regrets,” Deng wrote.

Many should have taken heed when Chinese state media reported that one of the Xi’s favorite films was “The Godfather.” Like Michael Corleone, Xi quickly out maneuvered his rivals within the party and consolidated power through anti-corruption and loyalty campaigns and muted the influence of retired party members.

‘Redder than Red'

Much more prescient at the time was the leaked 2009 U.S. State Department cable entitled “Portrait of Vice President Xi Jinping: ‘Ambitious Survivor’ of the Cultural Revolution.” Sourced from a private acquaintance of Xi, the summary read “Xi is ‘exceptionally ambitious’ confident and focused, and has had his 'eye on the prize' from early adulthood.”

Unlike many youth who "made up for lost time by having fun" after the Cultural Revolution, Xi "chose to survive by becoming redder than the red."

If the Party was China’s church, Xi is the ultimate true believer and, in Xi’s China, there is no separation between church and state.

During the last party congress in 2017, Xi triumphantly declared, “Government, the military, society and schools, north, south, east and west -- the party leads them all.”

Standing between China and chaos

The exact same day as Kristof’s optimistic column on Jan. 5, 2013, the true Xi revealed himself to the party elite, delivering a secret speech that was only published in its entirety in the party’s magazine “QiuShi” -- Seeking Truth” in 2019.

“Hostile forces at home and abroad … doing all in their power to smear and vilify,” he warned. “They aim to incite [the people] into overthrowing both the Communist Party of China’s leadership and the socialist system of our country.”

His internal party speeches at that time reveals Xi’s greatest motivating factor: for the Communist Party of China to avoid the fate of the Soviet Union.

In party study sessions, Xi would often pose the question, "why did the Soviet Union disintegrate? Why did the Communist Party of the Soviet Union fall to pieces?

“In the end, no one was man enough, and no one came out to fight,” he answered in one speech.

This was the period of the Arab Spring when popular uprisings in the Middle East overthrew their authoritarian dictators, Xi saw crises everywhere and a strong Communist Party with him at the helm was the only thing standing between China and chaos.

During this time a secret document circulated within the party known as “Document No. 9” which warned that western democratic ideals like universal values, civil society, free market economy and the West’s idea of journalism threatened China’s security and needed to be eradicated. It read like roadmap for Xi’s eventual heavy hand.

A veteran Chinese journalist was later sentenced to seven years in prison for leaking the document deemed "a state secret" to an overseas media outlet.

There are no official polls in China but by all accounts, Xi enjoys popular support by those who have not been negatively affected by his policies. The Chinese government often points to a Harvard survey that found that 95.5% of Chinese respondents in 2016 were either “relatively satisfied” or “highly satisfied” with their government.

As he is poised this weekend for even greater power, Xi once again highlighted looming external threats in his speech in front of the congress this week and doubled down on the path he has set for China and, by extension, the world.

“The world has entered a new period of turbulence and change,” Xi warned the delegates. “External attempts to suppress and contain China may escalate at any time.”

“We must therefore be more mindful of potential dangers, be prepared to deal with worst-case scenarios, and be ready to withstand high winds, choppy waters, and even dangerous storms.”