Reporter's notebook: Journeying into the savanna of Kenya's Maasai Mara

"Nightline" co-anchor joined legendary filmmakers Dereck and Beverly Joubert.

"Nightline" co-anchor Juju Chang and "Nightline" producer Cho Park traveled to Kenya's Maasai Mara in February. Their report will be featured in the one-hour National Geographic special "BORN WILD: The Next Generation," premiering Wednesday at 8 p.m. ET on National Geographic and Nat Geo WILD.

We’re all sweating under the African sun, straining to remain perfectly still as we focus on a lioness gingerly using her teeth to pick up one of her four newborn cubs.

Her lethal jaws, powerful enough to bring down a 300-pound wildebeest, are maternal enough to carry her 4-week-old cub for a few yards along the Kenyan savannah. It’s her way of keeping the other three cubs marching along despite their fatigue. The tiny trio scampers to catch up.

As I watch the legendary wildlife filmmaker Dereck Joubert calmly capture the rare moment, the cub's little face fills the viewfinder of Dereck's giant "Red" camera — a favorite of Holly wood directors. His wife, Beverly, is also focused on the cub with her massive DSLR camera, which sports a camouflage lens cover that’s easily 2 feet long. Everyone, including our National Geographic and ABC News film crews in the other safari truck, seems to be holding their collective breath. My jaw hangs open.

During their prolific, nearly four-decade career, the Jouberts have released 40 wildlife films, earning Emmys and a Peabody along the way. Their grueling projects have often required months of living alone in the wilderness without seeing another human save for the aircraft pilot who’d wave from overhead as he airdropped supplies. Their latest film on the Botswana Okavango Delta just premiered at the Sundance Film Festival.

The Jouberts look like modern versions of Meryl Street and Robert Redford in Hollywood's romantic mythology about this continent "Out of Africa." They are effortlessly chic, stylish iconoclasts.

Dereck’s piercing blue eyes constantly scan the horizon. Under his Australian Akubra hat, which looks like an American Stetson, sits a perfectly tousled white mane and matching beard framing his weathered, handsome face. At 63, he’s every bit the mature, regal lion surveying the great plains of Africa.

Beverly’s face is impossibly beautiful. I study her delicate nose and high cheekbones knowing that three years ago, just before she was gored by a cape buffalo, her face had been smashed in dozens of places. Her orbital socket was crushed, a bone chip resting on her optic nerve. During the long wait in the bush for a rescue helicopter, she lost five pints of blood. Humans normally have about eight. All of the doctors were shocked that she survived. Her still lithe former dancer’s body shows no trace of those grave injuries. But she’ll charmingly show you the slight scar under her eye and on her temporal lobe.

They’ve both survived and thrived while the wild animal species they’ve charted are dwindling. The Jouberts tell me that in their lifetime, the global lion population has gone from 400,000 to 50,000. Leopards have fared even worse; their numbers dwindling from 500,000 to 6,000.

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, there are estimated to be fewer than 20,000 African lions. NatGeo's Big Cats Initiative supports scientists and conservationists working to save big cats, and has supported more than 100 innovative projects to protect seven iconic big cat species in 27 countries.

We’re here in Kenya’s Maasai Mara, named after the famed Maasai tribe, which is known for its lion-killing warriors and colorful beadwork that tourists scoop up. We’re filming a National Geographic special for Earth Day called "BORN WILD: The Next Generation," airing Wednesday, April 22, at 8 p.m. EST.

The Jouberts picked this fertile region knowing it would be bursting with new life. Indeed, we see pregnant hyenas, zebras and a wildebeest just minutes after birth — so fresh we can see the placenta still attached. The Mara is an extension of Tanzania’s Serengeti and it is the ancient backdrop for the “great migration” of wildlife. There are a million wildebeest alone, not to mention zebras, gazelles, giraffes and elephants.

After spotting the lioness pick up her cub in her mouth — something we’ve all seen on nature documentaries — I’m surprised by what the Jouberts say next.

“During our 38 years of living in and following big cats in the wilderness, we’ve only captured that maternal gesture maybe 10 times," Beverly tells me, her genuine delight clear in her smile.

The moment's rarity suddenly enhances its beauty.

The lone lioness had given birth to her four cubs in a thicket of bushes about a month earlier. She nursed them during the day and left them alone while hunting at night. Over time, however, the scent of baby lions in those bushes would attract other predators.

This lioness instinctively knew she had to move her newborns to a “clean” thicket. This becomes their first precarious pilgrimage through open grass to safety. If a pack of hyenas sees them, the lioness wouldn't be able to protect them all. Our NatGeo executive producer Ann Prum called them "little soldiers” on their first long march across the open grass to the next oasis of trees. Prum, an inveterate award-winning wildlife filmmaker in her own right, is a fierce yet gentle lioness to her own young production staff.

In the Mara, we find the lioness midway through the mile-long march. Occasionally, she lays on her back as if to suckle the cubs only to get up and keep walking when they'd scurry over. Again, she is incentivizing the little troopers to keep pushing.

During our week at the Jouberts' lodge, a part of the Great Plains Conservation, we kept coming across equally enchanting scenes. Our lucky stars seemed to align for each expedition. But it’s not by chance. The Jouberts work closely with the Maasai community, which employs 600 people across 16 luxury lodges.

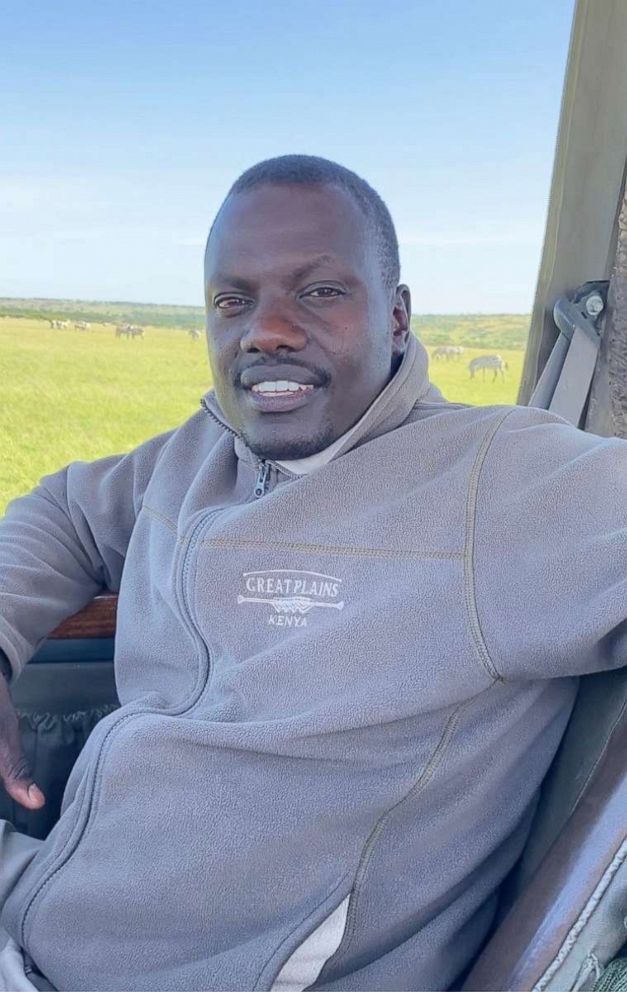

Our main guide at Mara Plains, part of the Great Plains Conservation, is a charming Maasai guide named Kevin Sayialel. His obvious tracking skills eclipsed only by his considerable knowledge of the terrain and the local wildlife. He’s too modest to tell us he’s the son of a very powerful former chief, or that he's the first of eight sons and eight daughters from three wives to attend college. His mother was the second wife. I tell him my grandfather had two wives.

“I will only take one wife,” he says with a mischievous grin. “Things are changing."

Two of his youngest sisters are also getting college educations. The biggest change of all.

The Maasai guides had been scouting the lions' prides across this region intensely in advance of our visit. But what are the odds that this would be the morning chosen to search for this mother lion? Yesterday, we met a pride of 18 lionesses and cubs. Another scouting expedition introduced us to two cheetahs known as the Maasai brothers. And yet another day brought us to a pregnant leopard, dozing in a tree as her cub jumped across a stream in a truly feline pounce — all directly in front of our cameras.

The most poignant evening was a sunset spent photographing an aging male lion lounging in the sunset. The Jouberts worry that he may die before his male cubs are old enough to fend for themselves. If another male defeats this lion, the new alpha male would kill his male heirs.

There are times, as we were sitting in a Land Cruiser, that we started speaking in hushed tones like one instinctively does when they enter a sacred space like a cathedral or holy sanctuary. We'd marvel at the pristine beauty of the landscape.

Kevin, our guide, would drive over unpaved parts of the great plains and casually point out four giraffes on the horizon. He’d explain their fighting and mating techniques before driving through muddy river beds and over rocks the size of footballs. The terrain is even more rugged because of recent flooding. We got a flat tire with Kevin, which he changed nonchalantly in about 10 minutes.

Dereck, too, drove into a sinkhole only to be wrenched out by Kevin’s vehicle. Only later did I remember that the Jouberts have a decades-long personal policy of never asking for help. I suspect they made an exception for me, the journalist from the urban jungle of New York City.

Born in South Africa, both Dereck and Beverly were children of gold mine workers. They met in high school. Dereck was clearly smitten by the young beauty and describes himself as relentless. He went off to the military, and after years of training In the wilderness, Beverly finally fell in love with the alpha male who she says always set himself apart from the pack.

Together, they fell in love with the wilds of Botswana. In early photos, Dereck looks like Robinson Crusoe and she looks fresh-faced and idealistic. I asked them how they passed all that time alone in the bush. Dereck chuckles and says, “I read the entire Shakespeare canon by candlelight to her." He also re-read his favorite, Dante Alighieri’s "Divine Comedy," while sitting at Beverly’s bedside — often wrapped in a Maasai blanket — during the months of rehab following her buffalo attack.

So many themes of the wild are embedded in Shakespeare’s works: life, death, treachery and blood-soaked battles for status and territory. The Jouberts' award-winning documentaries are laced with their death-defying adventures.

Dereck told me that he’s been bitten by no fewer than three deadly snakes, had 17 bouts of malaria, crashed three planes — not due to operator error, he tells me quickly — and survived 22 scorpion bites.

“We’ve outlived our nine lives," Beverly said jokingly.

They say they don't fear death but embrace it as part of the circle of life they witness day in and day out in Africa.

For "Born Wild," our Nat Geo crew is rounded out by Chris Onyando, a fabulous Kenyan drone operator with a light laugh and a deep baritone voice, and Edna Bonareri, an exceptional Kenyan sound tech. Both of their mothers are schoolteachers. Most Kenyans live in big cities like Nairobi and never make it out on safari. It’s a bit like New Yorkers who never visit the Statue of Liberty. Of course, the costs are prohibitive as well.

Prum, our troop leader, refers to Marc Caroll, our cameraman based in Nashville, Tennessee, as a human Swiss Army knife. He could be Matt Damon’s brother, I swear, with a friendly smile and earnest outlook. A veteran wildlife photographer, his specialty seems to be extreme explorations such as underwater scuba shoots, even in frozen terrain. The Jouberts are among his childhood idols.

By comparison, our youthful "Nightline" producer, Cho Park has never been to Africa. Her specialty? Hard-hitting, hard-nosed highly impactful investigations. But her enthusiasm for exotic animals keeps bursting out in gasps and giddy giggles. She gives all our veteran wildlife explorers the gift of being able to appreciate the epic landscape with its Noah’s Ark of animals through the wonder of virgin eyes.

After a few outings, I get it. That rush of adrenaline. The mystical escape. It feels like such a privilege, which is why well-heeled billionaires pay tens of thousands of dollars for a safari experience.

But for the Jouberts, wealthy adventurers are far different from trophy hunters. To them, there is no such thing as conservation hunting. They point out that for every male lion killed, 20 are wiped out in the natural reordering of prides.

And of course, human development and climate change impact the animals' habitat. Beverly told us about being in heat reaching 120 degrees Fahrenheit, “where animals in the wild are suffering." And if lions disappear, the great migration and everything in between suffers. It’s the lions who chase the wildebeests and the grazing animals across the savannah.

In my 30 years of traveling the planet as a journalist and storyteller, I’ve been through Africa many times, chasing the story of Boko Haram through Chad, Cameroon and Nigeria. Traveling to rural villages and through refugee camps in Tanzania and Mozambique. But for me, this is a rare, glamorous off-road safari that illuminates what is being lost every day.

On our final night in Kenya, our team joined hands with feeling. Full of gratitude at the wonders we witnessed and the stories of adventurous lives full of purpose. For explorers, there is a concept of “leave no trace wilderness." The Jouberts adhere to that ideal, leaving no trace of themselves in the untouched wilderness they inhabit. And yet, with all their conservation work and through their films, they’ve left quite an impression on the planet.