Titanic disaster still influences shipping lanes more than 100 years later

It was supposed to be unsinkable. But on April 15, 1912, it sank.

— -- It was supposed to be unsinkable.

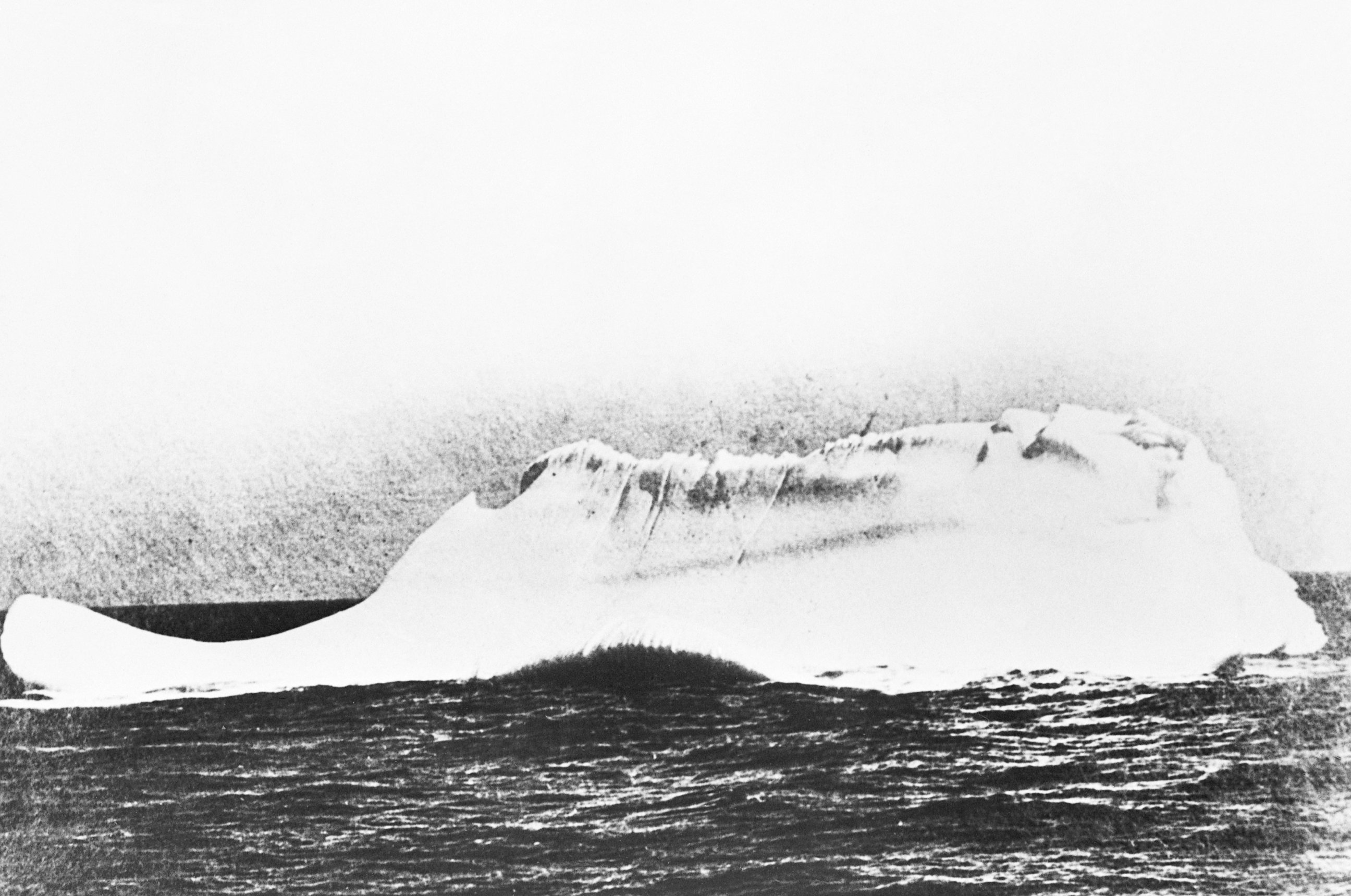

The RMS Titanic was a passenger liner that attracted some of the richest people in the world to sail on it. On its maiden voyage, the ship left Southampton, England, on April 10, 1912, with more than 2,200 people aboard on its way to New York City. Just four days later, it struck an iceberg just south of Newfoundland and sank. The tragic disaster influences Atlantic shipping lanes more than 100 years later.

The Titanic had been called unsinkable for many reasons, but one was that it had 16 watertight compartments to help keep it afloat. According to ship engineers, the Titanic could afford to flood four of those compartments and still sail. However, the iceberg flooded at least five of those compartments -- ultimately dooming the ship.

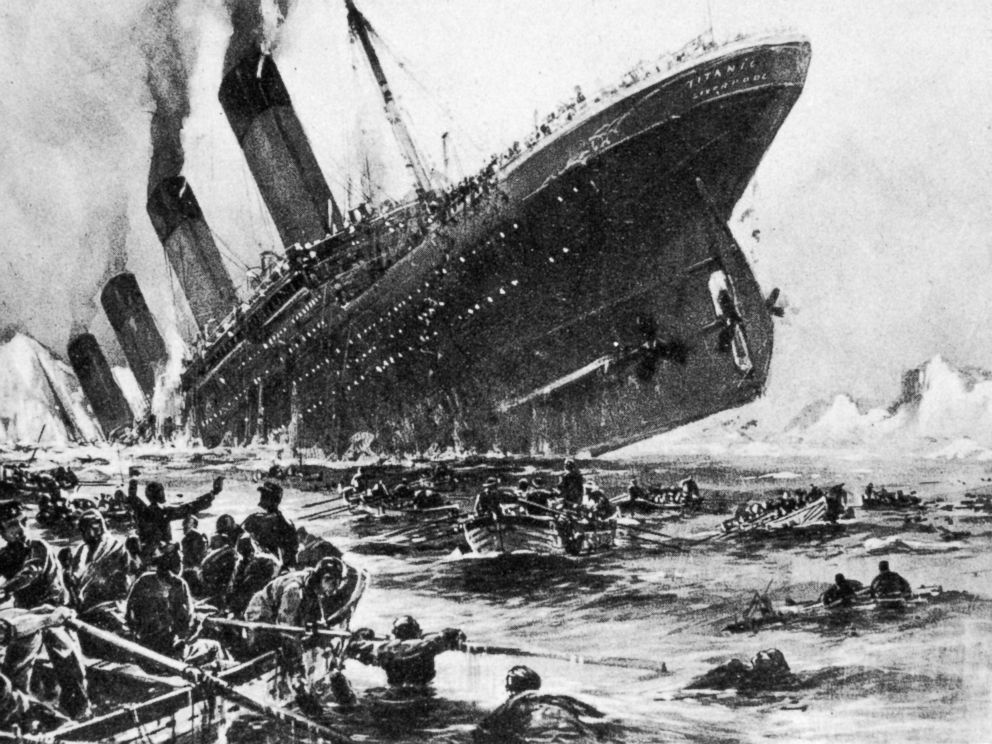

While the flooding was taking place, many passengers were evacuated in lifeboats. Most of those evacuated were women and children, as it was tradition to prioritize them. There also were not enough lifeboats on the ship to accommodate all the people were on board.

Less than three hours after the Titanic struck the iceberg, the ship broke apart. More than 1,000 people were still on board at that time. It sank in the North Atlantic in the early hours of April 15.

More than 1,500 people lost their lives in the sinking of the Titanic. Only one in five of those victims' bodies have been recovered. A little over 700 survived.

The wreckage of the Titanic was not discovered until the summer of 1985. It led to multiple films about it, including the 1997 award-winning film by James Cameron.

Historians debate what is to blame for the Titanic sinking. From Edwardian hubris to the captain not heeding ice warnings to the actual construction and planning of the ship itself, the sinking of the Titanic remains one of the most famous sea disasters in history.

The Titanic's tragedy still affects ships to this day. Hundreds of icebergs drifted into the North Atlantic shipping lanes in early April. This is unusual so early in the year, and the icebergs have forced shipping vessels to detour or slow their speed significantly to avoid impact.

As of March 29, 2017, there were 455 icebergs near the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, which is a significant increase from the 37 icebergs recorded just two days prior, according to the U.S. Coast Guard's International Ice Patrol in New London, Connecticut. Statistically speaking, that amount of icebergs is typically not reported until late May or early June. These icebergs have been reported very close to where the Titanic sank.

Coast Guard Cmdr. Gabrielle McGrath, who leads the ice patrol, said she has never seen such a drastic increase in a two-day period in the decade she's been working with the patrol. She blamed the recent significant increase on a low-pressure storm system that produced hurricane-force winds in the area, causing more icebergs to calve off.

The International Ice Patrol was formed after the sinking of the Titanic to monitor iceberg danger in the North Atlantic and warn ships. It conducts reconnaissance flights, which are then used to produce charts.

"[The international community] didn't want such a disaster to happen again, so they looked into what kind of measures they could put in place to prevent it," McGrath told ABC News.

Climate scientists are attributing the increase in icebergs to uncommonly strong counter-clockwise winds that are drawing the icebergs south, as well as global warming, which is accelerating the process by which chunks of the Greenland ice sheet break off and float away.

In 104 years, no ship that has heeded the warnings has struck an iceberg, according to the ice patrol.

"For vessels heeding our warnings, there has not been a collision since," McGrath told ABC News. "There was a collision in 2010 ... but they were inside our warning area."

The icebergs the patrol typically finds in the shipping lanes measure anywhere from 16 to 131 yards long. McGrath said in the 1950s and 1960s, the patrol experimented with trying to destroy the icebergs, even using bombs to blown them up.

"It's almost the opposite of what you want because you're just turning a bigger iceberg into a lot of smaller ones," McGrath told ABC News. "Even the smaller ones can cause an even bigger problem. After those tests, we determined it wasn't a great idea."

McGrath told ABC News that the ice patrol now just tracks the icebergs, forecasting their movement through the water and sending out a warning to vessels in the area.