The Electoral College is flawed -- so are the alternatives: Experts

Election experts broke down some of the alternatives and their risks.

Democracy is built on majority rule and the concept that every person's vote counts.

Yet five times in history, American presidents have won office while losing the popular vote, with two of those instances coming in the past 20 years -- George W. Bush in 2000 by a margin of around 500,000 votes and Donald Trump in 2016 by about 3 million.

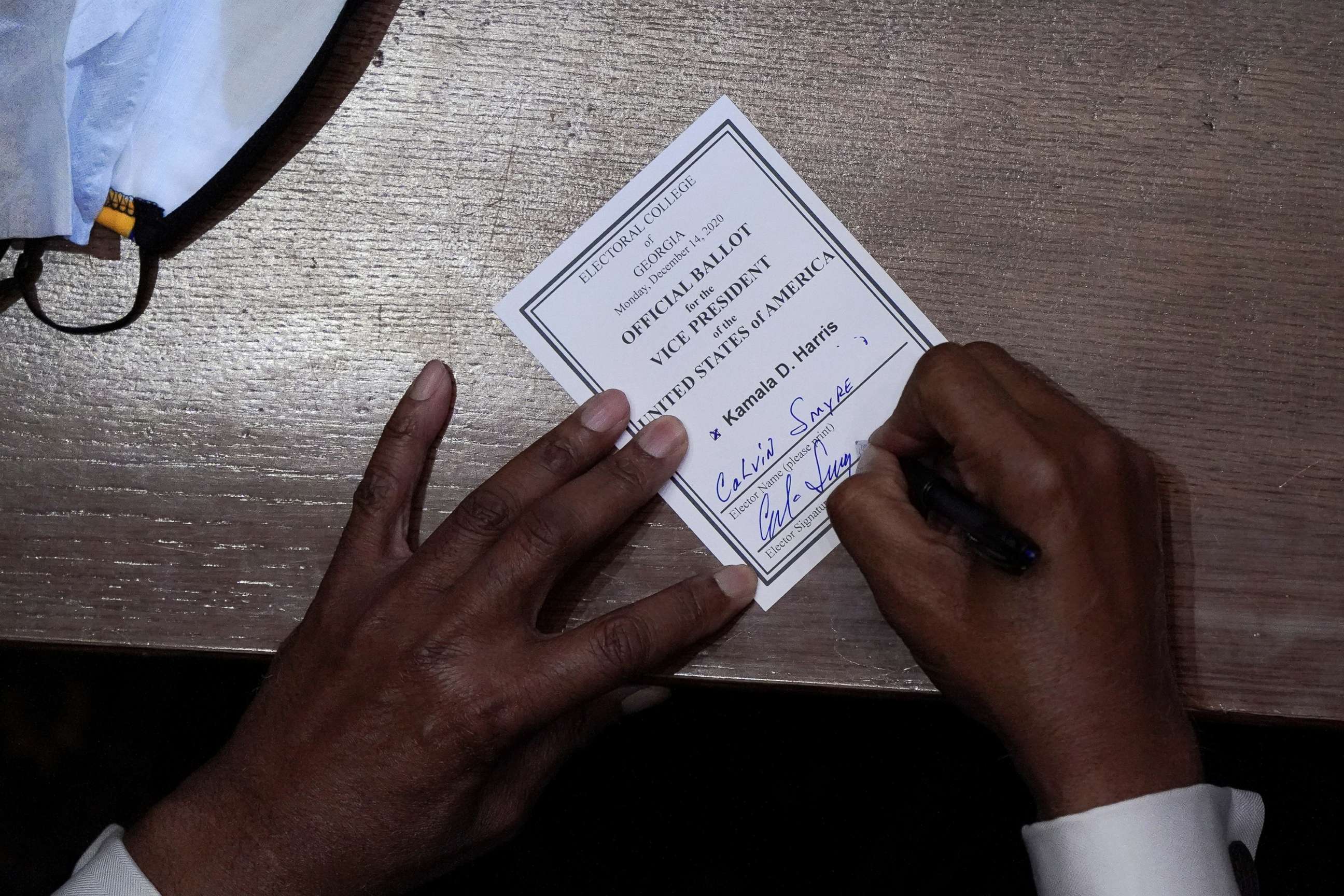

At issue is the uniquely American system of the Electoral College, which provides that a group of specially chosen representatives (538 at present) for each state choose the president, generally using a winner-takes-all model based on the popular vote.

The system was a compromise for the framers, making concessions to count slave populations in the otherwise less populated South and not placing too much trust in either Congress or the public with choosing the president. But the end result in recent years, as the urban versus rural divide has deepened, is that a handful of battleground states have gained a disproportionate amount of power and prominence.

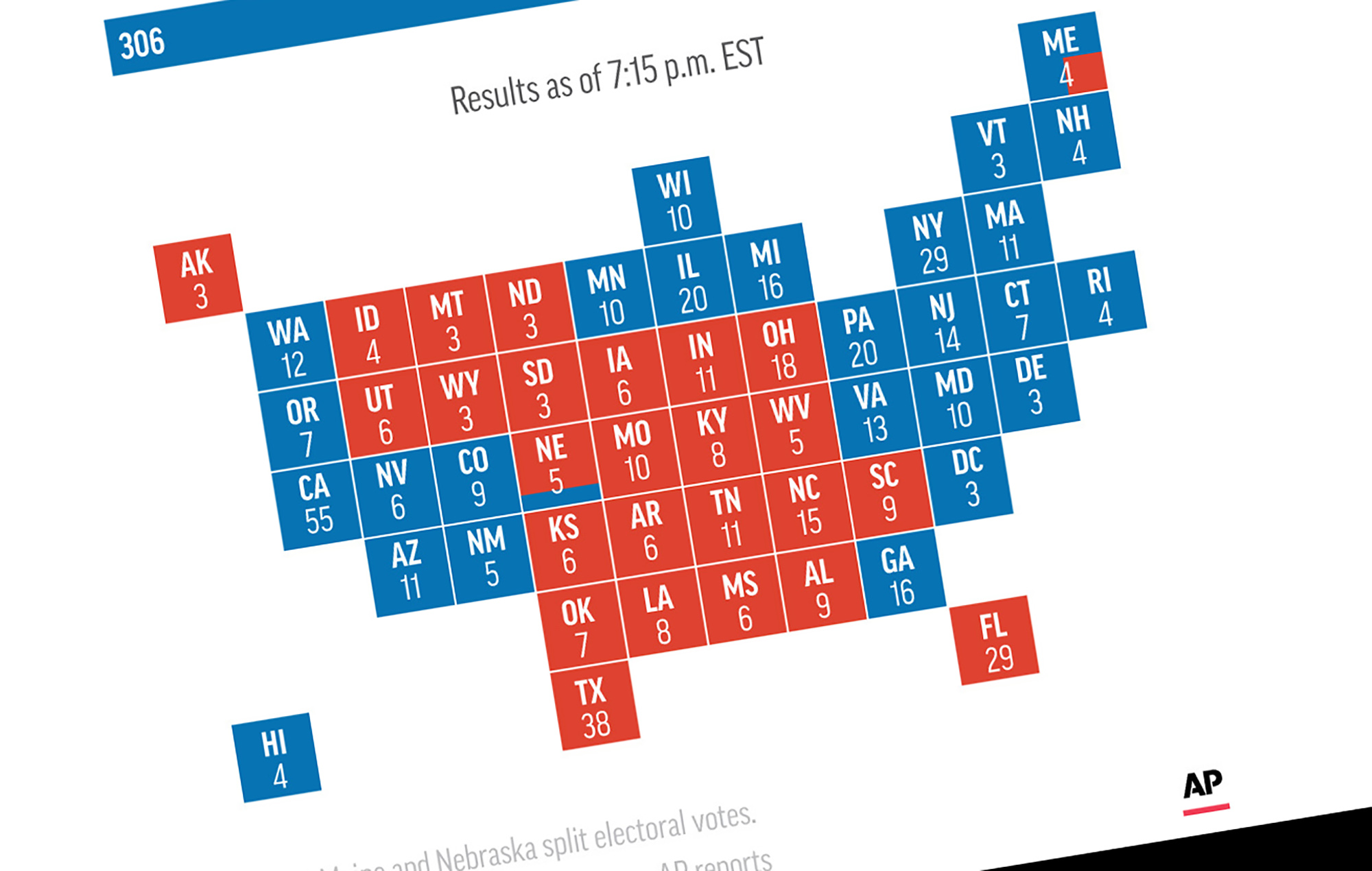

Even this year, with Joe Biden garnering some 7 million more votes than Trump (and 306 electoral votes), the margins in a number of battlegrounds were extremely close and the result was unclear for days, delaying the nation’s ability to call a clear winner.

Critics say that with the focus on battlegrounds while two-thirds of states are overlooked in campaigning, the system is fundamentally flawed, an assertion with which a majority of Americans agree (61%), according to the most recent Gallup poll.

But the alternatives to the system present a new set of challenges.

Here's what those might look like:

How could the country enact a popular vote system?

The popular vote isn't part of the constitutional process for choosing a president -- that is instead left up to the state legislatures and the Electoral College.

"There's no such thing right now as the national popular vote. It's just a bunch of 50 state races that get added together," explained Barry Burden, political science professor and founding director of the Elections Research Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

While a direct popular vote is an attractive idea at first glance, with advocates arguing it would ensure the candidate with the most votes wins, encourage vote turnout and force candidates to campaign outside battleground states, switching to a direct popular vote system would create complications that don't exist now.

Election experts questioned the administrative structure that would be the official "calculator" for the popular vote (since elections are administered by states) and one speculated the change could even lead to federal oversight of state polling sites.

Voter qualifications also differ by state, the experts said. For example, some states have restrictions on felon voting rights while others don't and experts said a popular vote could lead states to expand voting to 17-year-olds, for instance.

"If states were left in charge of running their own elections, some states would have incentive to try to run up the vote and expand the electorate. And not saying that's a bad thing, but people need to think about it," said Robert Erikson, a political science professor at Columbia University.

A direct popular vote would also open the field to a greater extent than it is now to third parties, creating the potential for a candidate to win the White House without more than 50% of the vote and raising questions of whether the government would conduct a national runoff.

A constitutional amendment might be the cleanest way to address these questions in advance, but even if parties were able to garner bipartisan support on what that might look like, amending the constitution is an arduous task. There have been nearly 800 attempts to eliminate or reform the Electoral College and not a single effort has succeeded.

"While I'm very sympathetic to the national popular vote philosophy, because the individual voter, no matter where they live should be equal to the greatest degree possible, actually turning the national popular vote into reality is a pretty complicated thing," said Jay Barth, a longtime politics professor at Hendrix College in Arkansas. "A constitutional amendment would answer a lot of these questions on the front end rather than having to figure it out on the fly."

The problem with 'winner-takes-all'

Some argue the system can be reformed without changing the Constitution and that the real problem with the Electoral College stems from 48 states using a winner-take-all method in awarding its states electors.

While giving states the power to choose how its electors are awarded is enshrined in the Constitution, the winner-take-all method of granting them is not. Under winner-takes-all, a state awards all of its electors to the candidate with the most votes no matter how small the margin of victory -- effectively discounting millions of votes.

John Koza, chairman of nonprofit National Popular Vote, said it's the winner-take-all system that has enabled five presidents to take office without winning the most votes nationwide and encouraged candidates to focus on closely divided battleground states that don't represent the country at large. As there have been fewer landslides in presidential races yet the electoral vote remains competitive, he said, the current system will continue to generate uncertainty, recounts and litigation, despite the popular vote winner being clear on election night.

In addition to Trump and Bush, Presidents Benjamin Harrison in 1888, Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876 and John Quincy Adams in 1824 also took office having received less popular votes than their competitors.

"Without reform, the system is a ticking time bomb," Koza said, noting the potential catastrophe if a candidate who lost the Electoral College but won the popular vote refused to concede. That could have happened in the 2000 election, in which the popular vote was close and the contest hung on one state, Florida. Although concessions aren't required, there's potential to cause a lack of faith in the system without them.

Burden agreed that the nature of winner-take-all laws puts the spotlights on a few states and can encourage litigation and suspicion.

"The Electoral College sort of amps up the partisan animosity in those states where each side is distrustful of the other side. It draws attention to the small aspects of election laws in those states that end up being really consequential because a few thousand votes in a place like Wisconsin or Georgia could change the outcome of who wins the White House," he said.

Koza said that apart from post-election chaos, the deleterious effects of winner-takes-all can be felt on the campaign trail. According to the National Popular Vote, two-thirds of states are routinely skipped in presidential election campaigns -- including 12 of the 13 smallest states, which supporters of the current system say it's designed to protect.

Two of the states with the most electoral votes -- New York and California, have not voted for a Republican for president since the 1980s. Texas has not voted for a Democrat since 1976, although there is regularly talk about the state turning purple.

"When people say that they don't vote in the presidential race -- the most interesting race -- because their vote doesn't count, they're absolutely correct depending on where they live, " said Koza. "We don't like to put it that way because there's plenty of other offices to vote for, but the reality is, voters' votes don't count. And that's evidenced by the fact that the turnout is higher in the battleground states than in the rest of the country."

His solution: the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, an agreement among states to pledge to cast all of their electors to whomever wins the national popular vote, regardless of their state result. If states possessing at least 270 electoral votes were to sign on, the pact would ensure that the presidential candidate who received the most votes nationwide took office.

Currently, legislatures in 15 states and Washington D.C. -- representing 196 electoral votes -- have enacted the national popular vote bill into law, so if states having 74 electoral votes were to sign on, potentially a minimum of three more states, it would automatically go into effect.

Critics say that without the consent of Congress, the interstate pact is unconstitutional, and election experts, considering partisan politics, predict it will be challenged in court if enough states sign on.

Splitting the difference?

Others say instead of a winner-take-all system, states could turn to the example of Maine and Nebraska, which award electors by congressional district as well as the overall vote for those state's remaining two electoral votes. But that option could present more serious problems because of gerrymandering, with one expert deeming the system going nationwide a "Republican's dream."

Erikson said the system would shift politics in "crazy ways," he said, where instead of battleground states, competitive districts would get all the attention.

Awarding a state's electors based on a proportion of population to the popular vote is the alternative some experts said is the most viable solution.

Under this method, a state's electors could be split, encouraging candidates to compete for votes within every state to accumulate the highest possible number of electoral votes. However, it's unlikely every state would agree to switch to awarding its electors proportionally off the popular vote because of partisan considerations -- which is how the winner-takes-all system was enacted in the first place.

"Once one party was in control of a state, they realized that they could maximize their partisan influence by awarding all of the state's electoral votes to their preferred candidate," said Kermit Roosevelt, a constitutional law professor at the University of Pennsylvania. He explained that every state would have to switch to awarding its electors based on proportion of the vote to population at the same time, otherwise a state would be minimizing its power while other states held onto winner-take-all laws.

Burden also reminded there is a small-state bias already built into the Electoral College since every state gets three electors -- it's minimum number of senators and representatives combined -- so even with proportion by population, small states would still carry more electoral weight.

What are the prospects?

All of the alternatives have one problem in common: it will be difficult if not impossible to implement any of them given the partisan politics across the country.

At the national level, a constitutional amendment would require the approval of two-thirds of the Congress and then three-fourths of states' legislatures. States could bypass Congress by having two-thirds of state legislatures call a convention, but efforts using the convention method have never been successful. It's more likely the country will see states explore new ways to grant their electors.

Koza, who expects the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact to gain traction in the coming cycles, argues one of the reasons change is possible is "because neither party has a really convincing case as to why the current system helps them or hurts them."

While the system is currently benefiting Republicans now and has for a few election cycles -- experts say if Texas were to turn blue, the GOP might be more interested in alternatives like awarding electors based on a proportion of population.

"I hope that you people who care about America in a nonpartisan way would support reform, and also, forward thinking Republicans who can see demographic tides shifting against them in -- in Texas in particular -- I think it would be smart for them to get ahead of it," said Roosevelt.

"From a nonpartisan perspective, the case for reforming or abolishing it is pretty strong," he added. "Every time we have a presidential election, it's like riding a 220-year-old roller coaster, where with every twist and turn you wait to see if you're about to fly off the tracks. And we can do better than that."