'Hear ye! Hear ye!': Ritual and 18th century language evoke history at Senate trial

The Senate is following a script that dates back centuries.

In contrast to the name-calling and partisan chaos that dominates current Washington politics, the Senate impeachment trial is a solemn affair, remarkably orderly and measured, and with its formal rules and 18th century language, a kind of scripted history in the making.

Some of the first words spoken on Thursday could have come from a town crier.

"Hear ye! Hear ye! Hear ye! All persons are commanded to keep silent, on pain of imprisonment, while the House of Representatives is exhibiting to the Senate of the United States articles of impeachment against President Donald John Trump, President of the United States," Sergeant at Arms Michael Stenger read aloud to senators Thursday.

The same words were spoken, the same way, in 1999 at President Bill Clinton's trial, and before that, in 1868, at the trial of President Andrew Johnson.

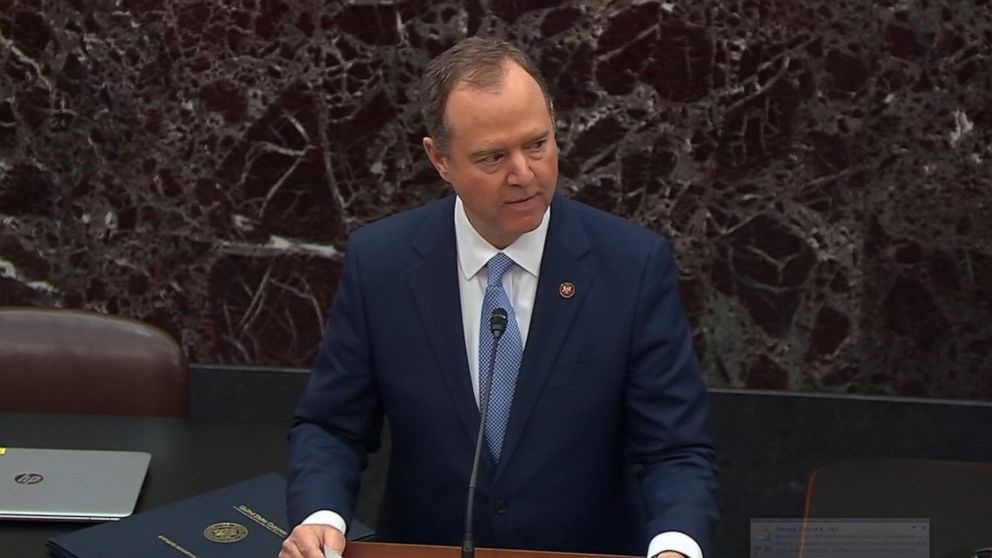

Also on Thursday, in keeping with the same rules governing those previous such trials, the Senate floor was opened so the lead House manager, Rep. Adam Schiff, D-Calif., could ritually read aloud, and into the trial record, the articles of impeachment about "high crimes and misdemeanors," and the House resolution that appointed the managers who will present the case against the president.

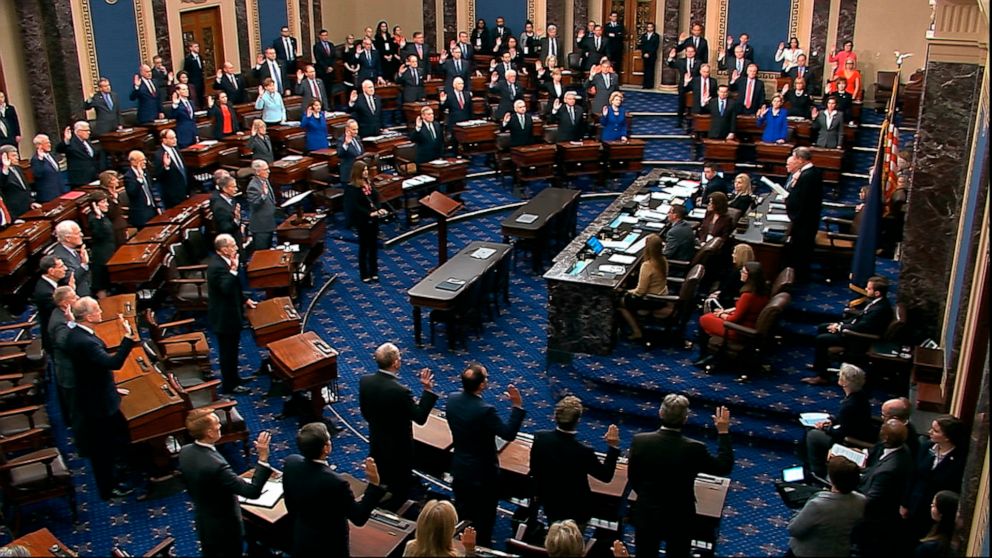

The oath taken by Chief Justice John Roberts -- who then administered the same to senators - is spelled out in Senate rules and dates back to the late 1700s.

“I solemnly swear that in all things appertaining to the trial of the impeachment of President Donald Trump, now pending, I will do impartial justice according to the Constitution and laws: So help me God,” it reads.

In the age of electronic record-keeping, an old-school account of all senators taking the oath is kept as each one steps forward, in alphabetical order, to use a ceremonial pen to sign his or her name in an "oath book."

During the trial, senators are not allowed to speak, or have electronic devices, and questions must be submitted in writing.

When and how long the Senate, sitting as a jury, must meet, are prescribed as well.

According to the 1868 rules, the oaths must be administered beginning "at twelve o'clock and thirty minutes afternoon."

The rules also say that the trial must continue six days a week, every day except Sunday, until it is over -- though that schedule is subject to change.

Just before adjourning Thursday, the Senate, just as it did more than 150 years ago, sent a ceremonial written summons to the White House, calling on the impeached president to appear and answer the articles against him.