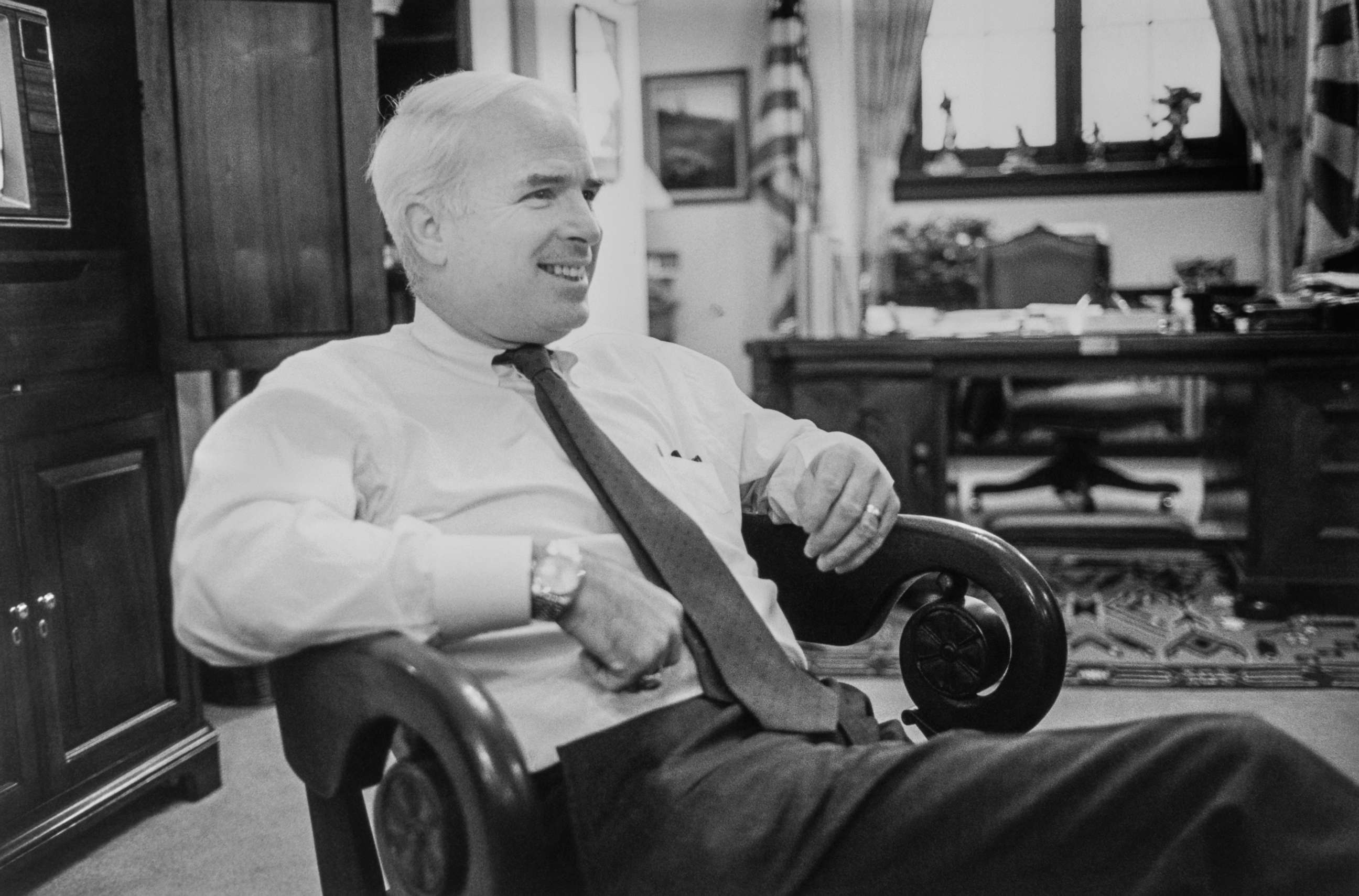

John McCain, a hero and leader who took causes more seriously than himself: ANALYSIS

For a hero and renowned lawmaker, McCain seemed to disappoint a lot of people.

For a war hero, renowned lawmaker, and a towering figure on the American landscape, John McCain seemed to disappoint a whole lot of people.

From tax cuts to campaign finance, detainee treatment and health care policy, Republicans often found reasons to be mad at the senator from Arizona. McCain sometimes bucked his party in Congress and clashed repeatedly and publicly with the past two GOP presidents – the current one in particular.

As for Democrats, their disappointment in McCain seemed to be renewed with every fresh realization that, for all his across-the-aisle friendships and independent political stances, he remained a solid conservative to the end, proudly holding Barry Goldwater’s old Senate seat.

McCain, who died Saturday at the age of 81, would probably laugh at this observation. He learned long ago - through a life that included deep suffering, both physical and mental - not to take himself, or things said by his critics, too seriously.

“I've been tested on a number of occasions. I haven't always done the right thing,” McCain said in an HBO documentary about his life that debuted in May. “The important thing is not to look back and figure out all of the things that I should have done - and there are lots of those - but to look back with gratitude. You will never talk to anyone who's as fortunate as John McCain.”

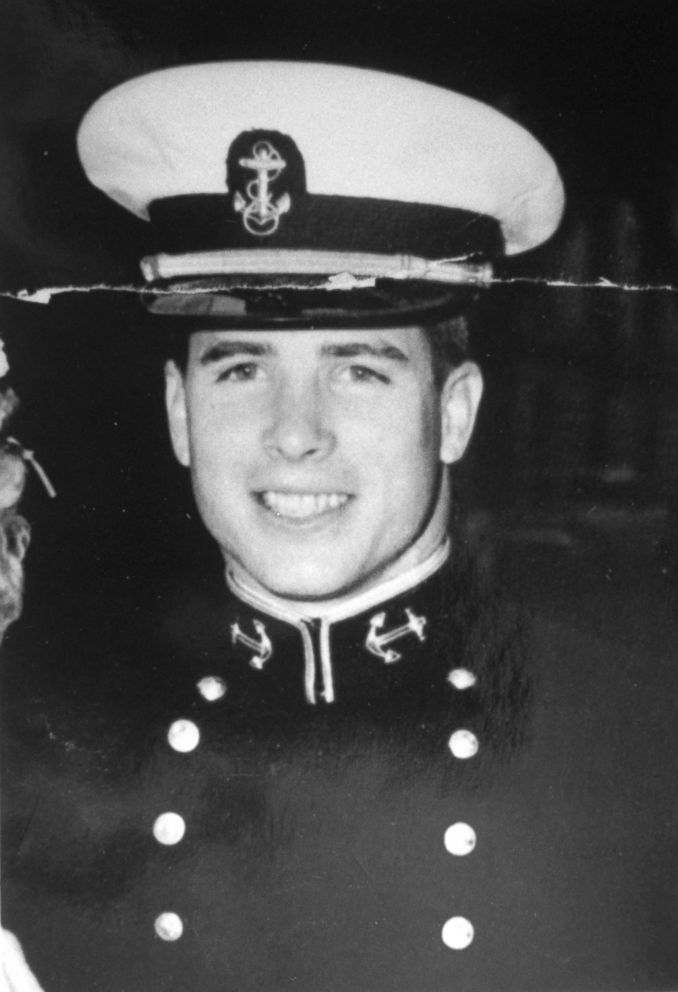

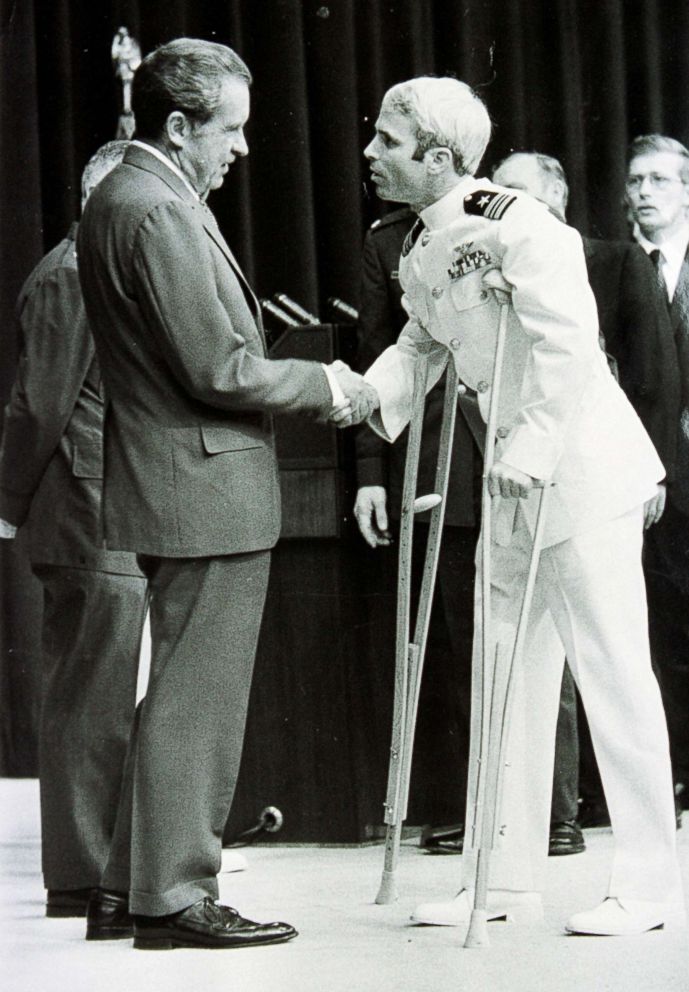

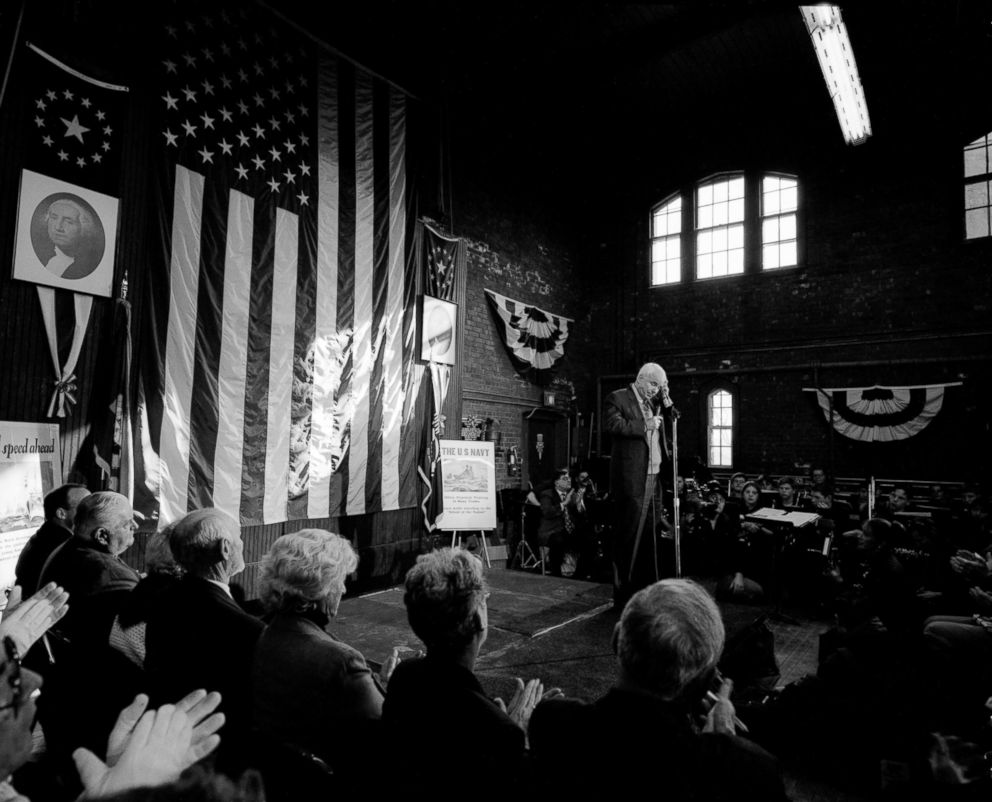

“Fortunate” may not have seemed an apt word to describe the 31-year-old Navy pilot after he was shot down over Hanoi in 1967. The son and grandson of prominent Navy officers, McCain was singled out for harsh treatment during the more than five years he was held as a prisoner of war in North Vietnam.

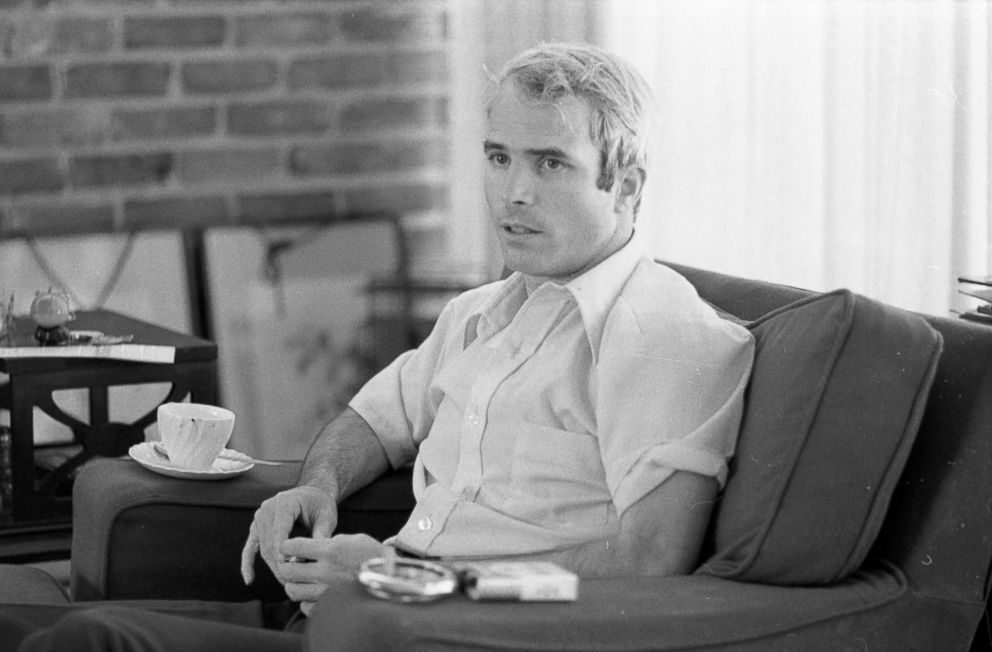

He came home a hero - notwithstanding any judgments rendered by a certain future president. But his war experience marked just the beginning of a remarkable career in public service that found him playing a central role in virtually all of the major domestic and foreign-policy debates of the past three decades.

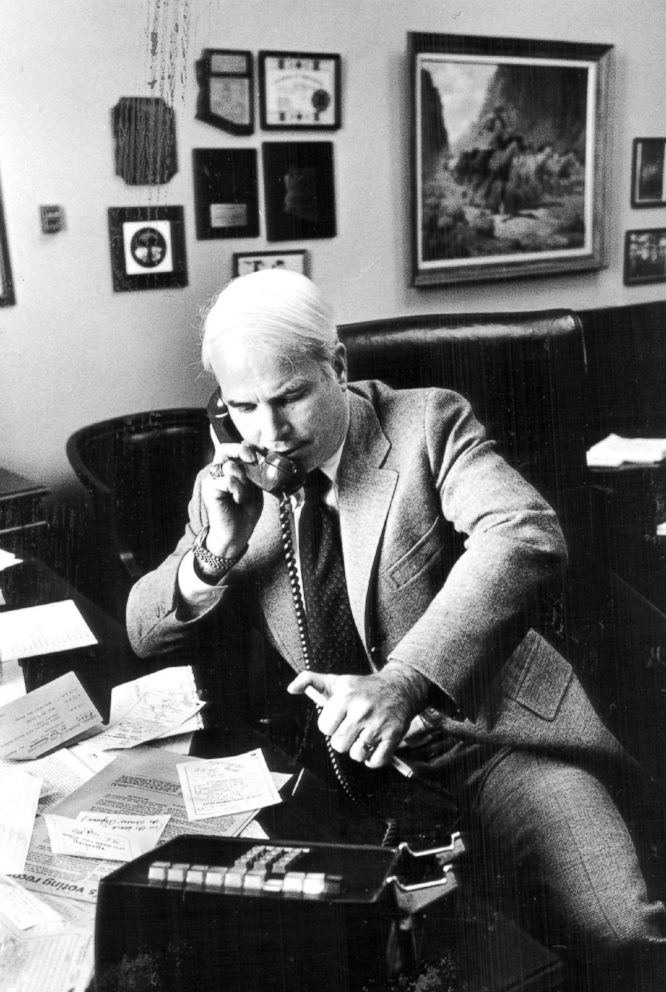

McCain was a force – kinetic, seemingly always in motion, bouncing between topics, meetings, and interviews with vitality and ambition. His specialty was less in deal-making than rabble-rousing, cobbling together alliances as they fit with his sometimes iconoclastic views.

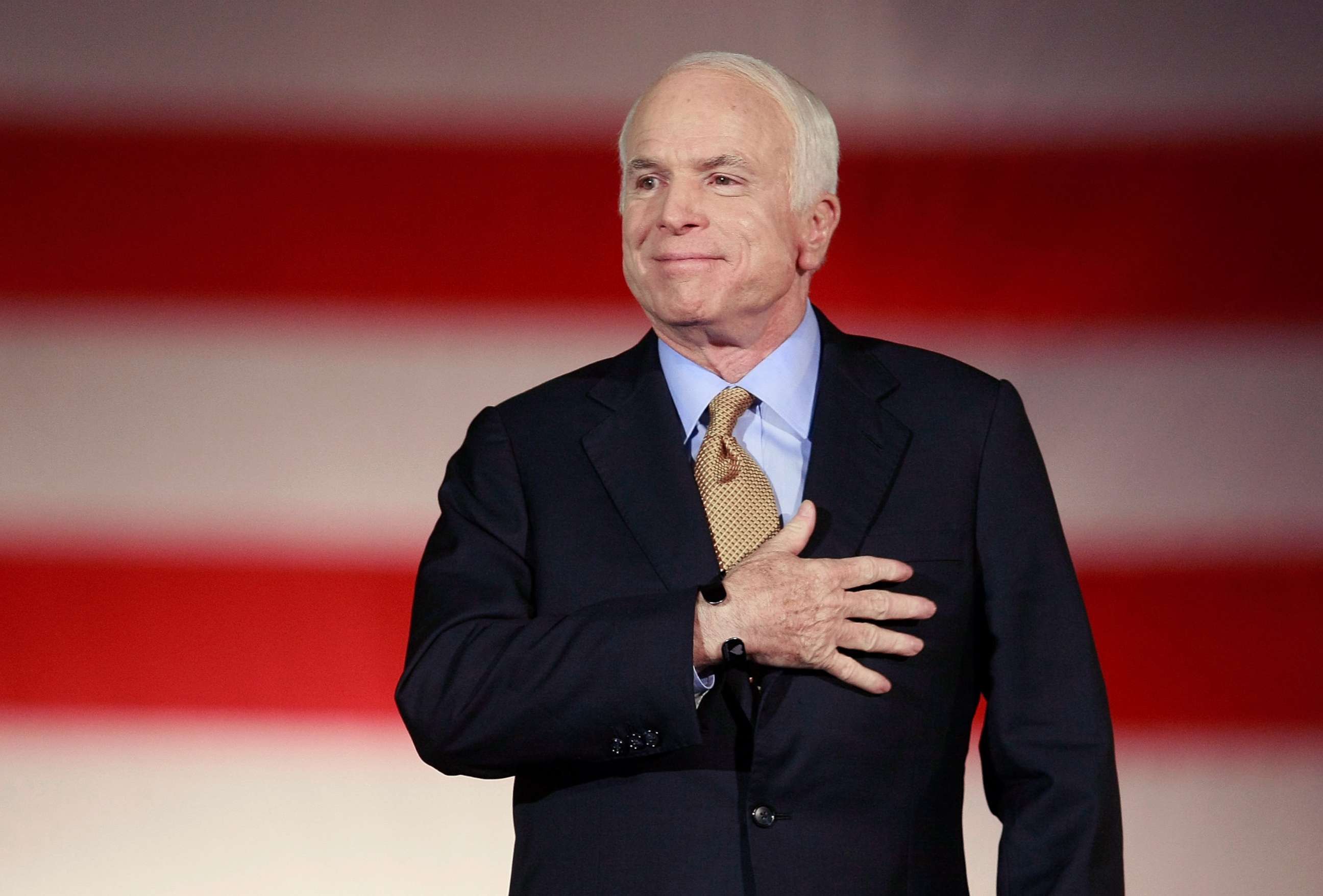

He was defined by his patriotism, his temper, his stubborn streak, and an unpredictable, mischievous nature. A term used to encapsulate his political behavior: Maverick.

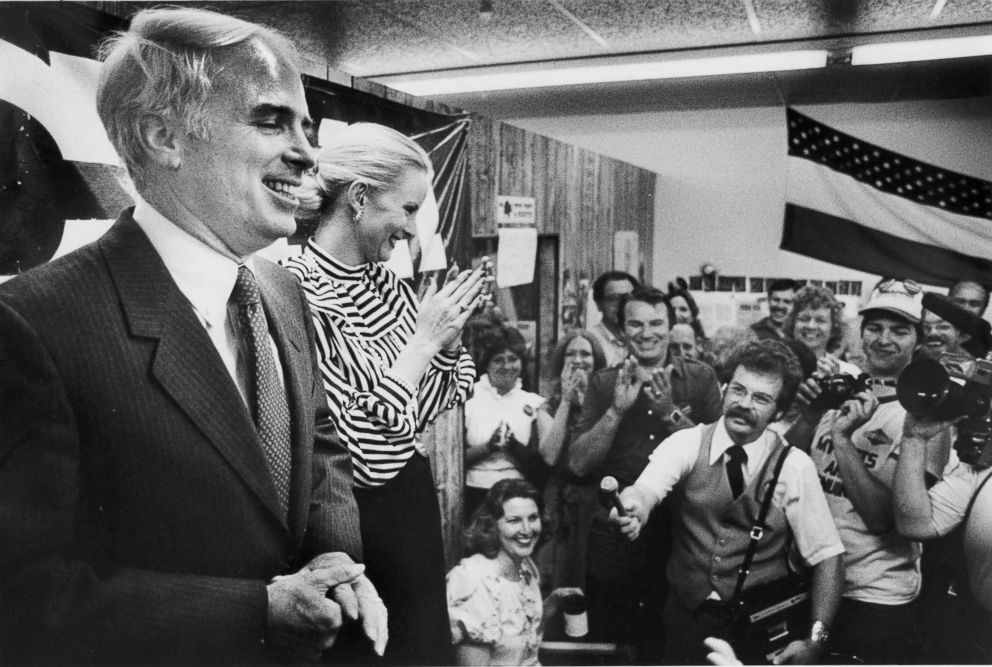

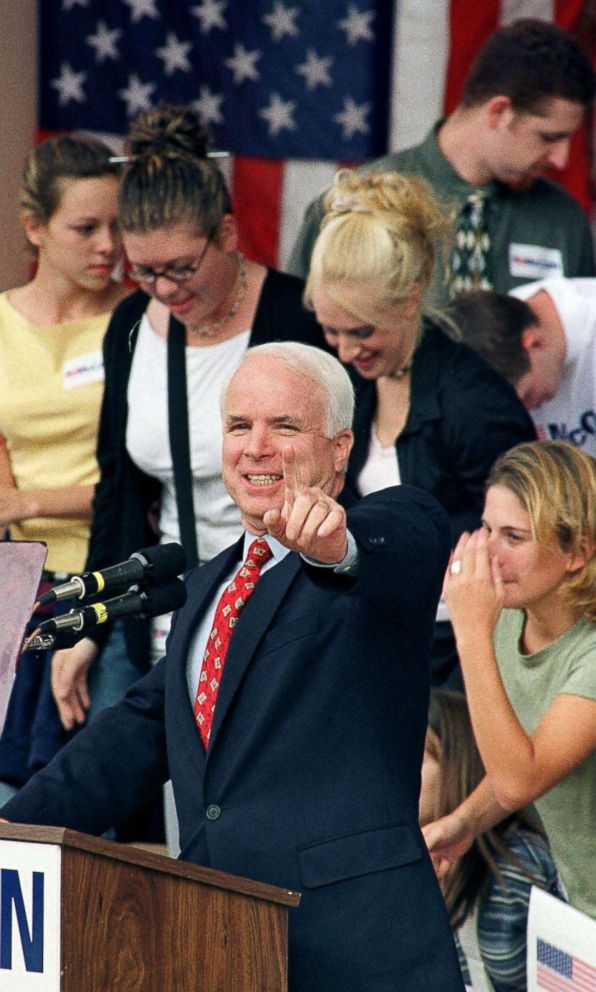

He rode that label onto the “Straight Talk Express” that took him through two campaigns for the presidency. His voice seemed to carry weight even when he was sidelined from the Senate by the cancer that would ultimately claim his life.

McCain was knowledgeable enough about himself and American politics to recognize his own weaknesses, traits that he could readily enumerate.

“Our deliberations can still be important and useful, but I think we would all agree they haven't been overburdened by greatness lately,” McCain told his Senate colleagues last summer, in one of the last major speeches he would make on the Senate floor.

He found blame for himself: “Sometimes I've let my passion rule my reason. Sometimes I made it harder to find common ground because of something harsh I said to a colleague. Sometimes I wanted to win more for the sake of winning than to achieve a contested policy.”

McCain did love winning -– a characteristic that may have played a part in what was arguably his political low point: His involvement in the savings-and-loan scandal of the 1980s, as a member of the so-called “Keating Five,” a group of senators accused of corruption for intervening on behalf of a savings-and-loan chairman who was a campaign contributor.

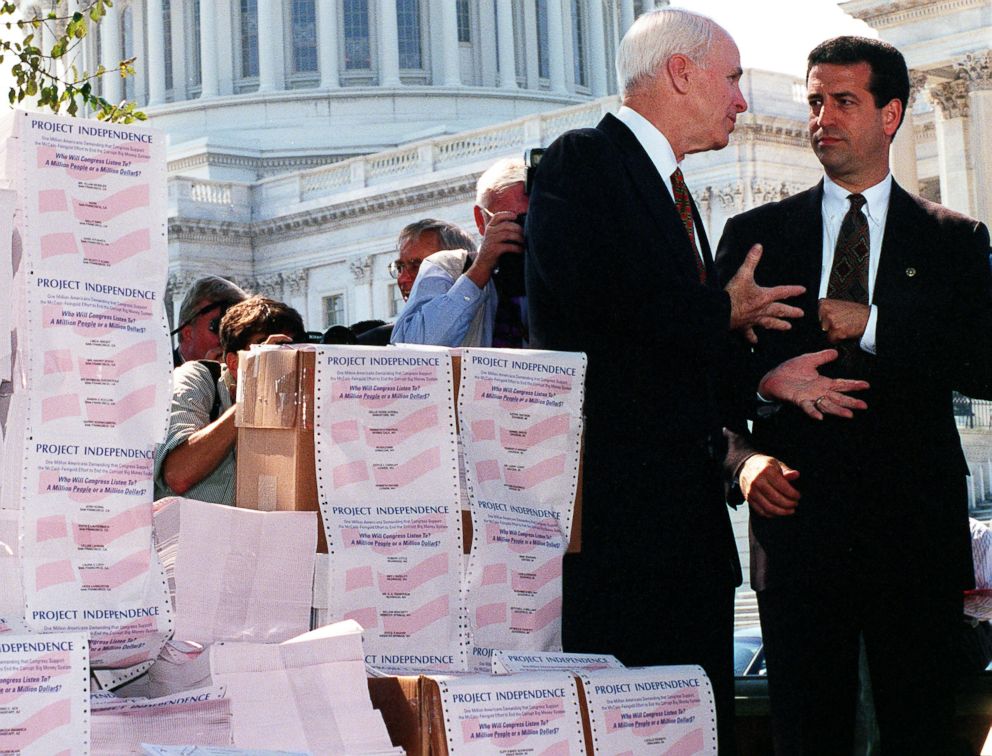

McCain accepted responsibility and used the experience as part of his inspiration for perhaps his biggest legislative accomplishment: The 2002 McCain-Feingold campaign-finance reform.

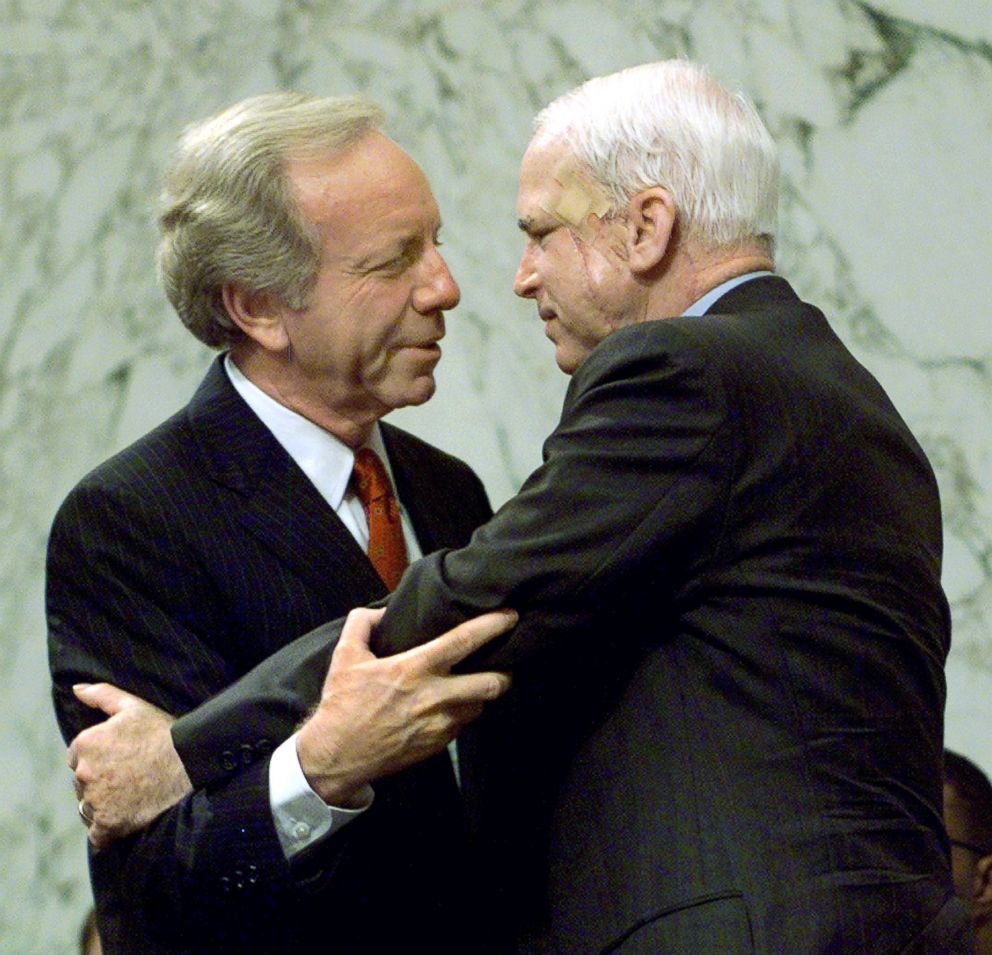

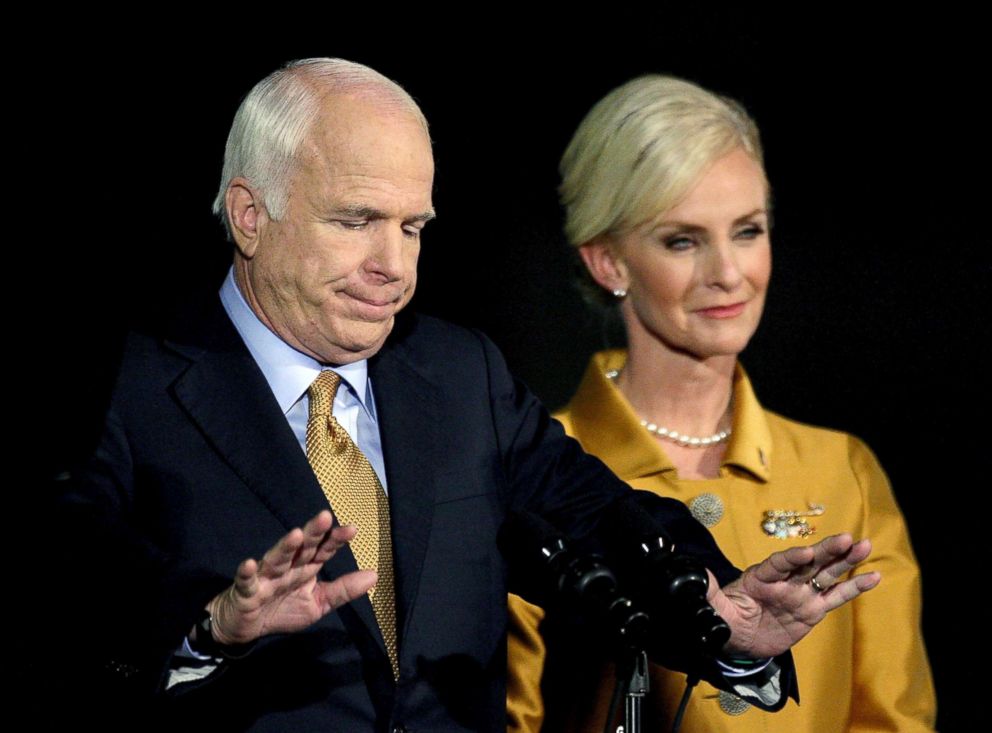

It was also his desire to win that led McCain to choose Sarah Palin as his running mate in 2008 – a nod, in the eyes of many, to the same brand of personality-driven populism that would make a harsh McCain critic president eight years later. McCain would later write that he wished he had chosen his friend Sen. Joe Lieberman, Al Gore’s former running mate, to join his ticket instead.

One moment in the 2008 campaign in particular will be remembered for what it said about the man. McCain had strongly attacked his opponent, Barack Obama, as a liberal who was unprepared for the presidency.

But when, less than a month before the hard-fought election, a woman at a town-hall meeting said she couldn’t trust Obama because he’s “an Arab,” McCain corrected her on the spot.

“No, ma'am,” he said. “He's a decent family man -- citizen that I just happen to have disagreements with on fundamental issues, and that's what this campaign's all about.”

Eight years later came a new president who fueled his political rise by questioning Obama’s citizenship. Early in his campaign, Donald Trump said of McCain, “He’s not a war hero … He was a war hero because he was captured. I like people who weren’t captured.”

McCain professed not to take the insult personally. The president, though, felt it personally when, six months into his time in office, McCain cast a shocking and deciding vote against an Obamacare repeal effort.

Trump has made that episode – complete with mockery of the “one senator” who decided “to put the thumb down” – a staple of his stump speeches, inviting the inevitable boos against McCain by Trump loyalists.

McCain felt no need to respond to such jabs. He was a partisan figure, but attacks and divisiveness didn't fit with his belief that the U.S. needed to return to shared sense of citizenship.

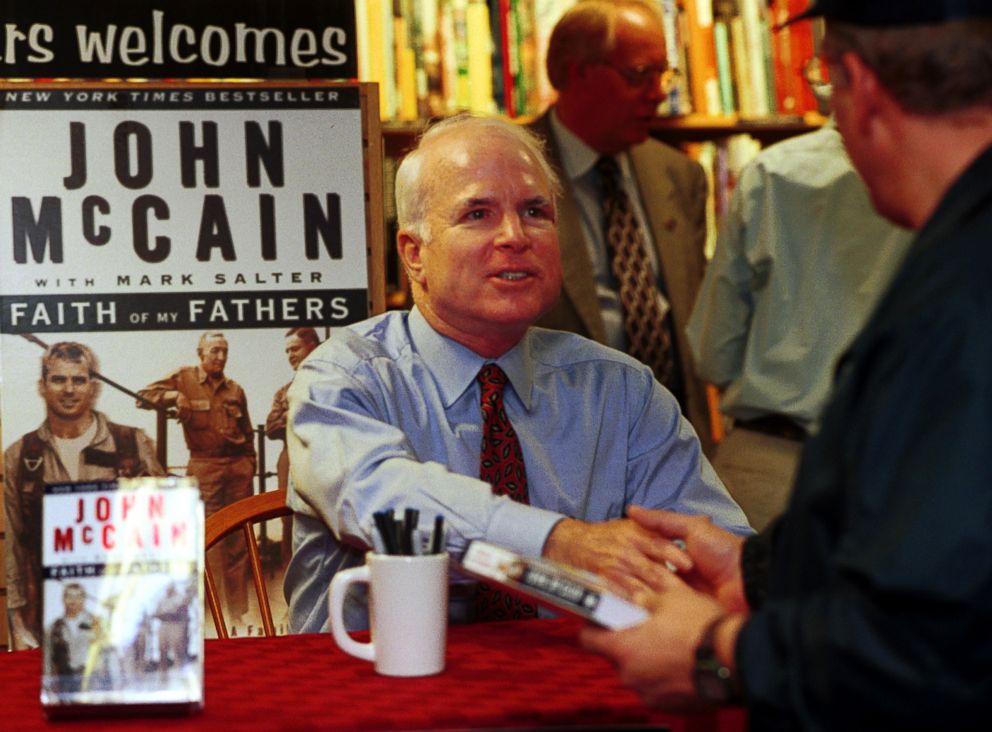

“I would like to see us recover our sense that we are more alike than different,” he wrote in his final book, “The Restless Wave,” published earlier this year.

In recent months, with McCain in declining health, a common Washington discussion point has revolved around who would be the “new” McCain -– someone with the profile and confidence to stand up to a president who flouts the norms of Washington with regularity.

Perhaps it would be his close friend, Sen. Lindsey Graham. It might be Arizona’s junior senator, Sen. Jeff Flake. Or it could be the rival McCain vanquished to secure the 2008 presidential nomination, Mitt Romney, who is now on track to win a Senate seat in Utah.

But Graham has become a Trump golfing companion. Flake is leaving the Senate, a casualty of speaking out against the president, with the GOP primary race to replace him a free-for-all over who would be Trump’s best friend.

And Romney, the former Massachusetts governor who broke sharply with Trump during the 2016 campaign, said recently that Trump’s time in office has been “better than I expected,” adding that “his first year is very similar to things I’d have done my first year.”

Perhaps the final disappointment over John McCain will be that there will not be another one like him. He himself would be disappointed not to live battle through this current era in politics, wild even by the standards he witnessed.

McCain was a rare politician who took his work and the causes of the nation more seriously than he took himself. Like his own literary hero Ernest Hemingway, McCain taught the nation that greatness could have nuance, that heroes are imperfect, and that honor comes from earning rather than burnishing a legacy.