Key takeaways from US military leaders on Afghanistan withdrawal

The military leaders appeared to contradict President Joe Biden's assertions.

In their first appearance before Congress since the withdrawal of all U.S. forces from Afghanistan, the nation's top military leaders candidly admitted to lawmakers that they had recommended to President Joe Biden that the U.S. should keep a troop presence there, appearing to contradict his assertions.

The testimony by Gen. Mark Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Gen. Frank McKenzie, the commander of U.S. Central Command, was at odds with Biden's comments earlier this year to ABC News' George Stephanopoulos that his military commanders did not recommend keeping a residual force.

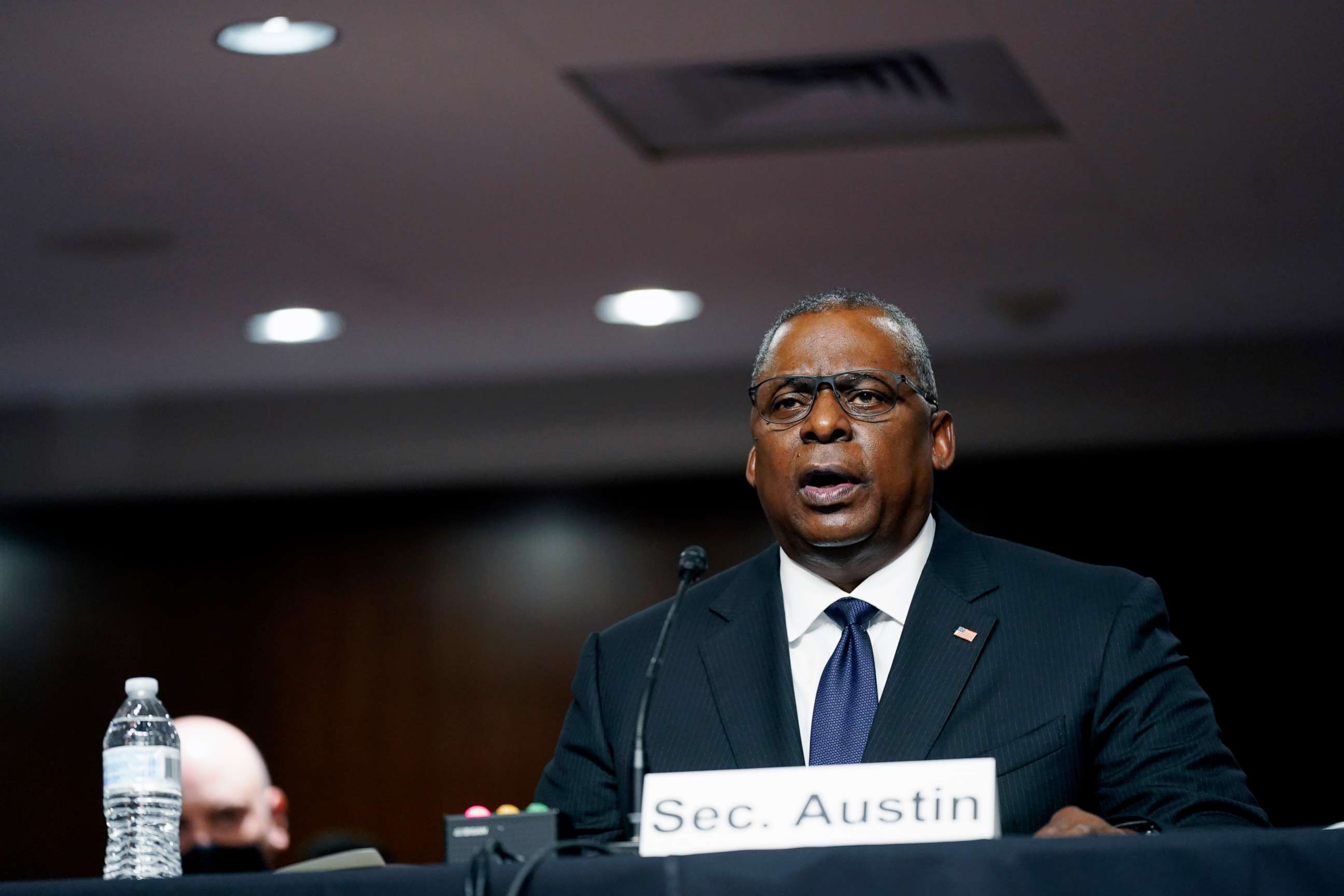

The revelations came during a six-hour hearing before the Senate Armed Services Committee where Milley also characterized that the U.S. military mission in Afghanistan had been "a strategic failure" and Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin acknowledged that it was time to acknowledged some "uncomfortable truths" about the two decade U.S. military mission in Afghanistan.

Here are some key takeaways:

Military commanders wanted to keep at least 2,500 troops in Afghanistan

While Milley and McKenzie said they would not disclose the content of private conversations with Biden, both generals offered their personal opinions that they said matched their recommendations.

"My assessment was back in the fall of '20 and remained consistent throughout that we should keep a steady state of 2,500, could bounce up to 3,500," Milley told Republican Sen. Tom Cotton of Arkansas.

"I recommended that we maintain 2,500 troops in Afghanistan, and I also recommended early in the fall of 2020 that we maintain 4,500 at that time, those were my personal views," McKenzie said.

The generals' statements were at odds with what Biden had told ABC's George Stephanopoulos in an interview on Aug. 18.

"No one told -- your military advisers did not tell you, "No, we should just keep 2,500 troops. It's been a stable situation for the last several years. We can do that. We can continue to do that?," Stephanopoulos asked Biden.

"No," said Biden. "No one said that to me, that I can recall."

Biden also said his military advisers were "split" on the matter.

McKenzie said he had also warned that the withdrawal of U.S. troops "would lead inevitably to the collapse of the Afghan government and the Afghan military."

"I also had a view that the withdrawal of those forces would lead inevitably to the collapse of the Afghan military forces and eventually the Afghan government," he said.

'A strategic failure'

Austin and Milley told senators that the sudden collapse of the Afghan government, as well as the U.S. military's mission in Afghanistan over the past two decades, should be examined to learn what may have gone wrong.

Milley became the first U.S. military leader to describe the American military mission in Afghanistan as "a strategic failure" that had developed over time.

"Outcomes in a war like this, an outcome that is a strategic failure — the enemy is in charge in Kabul, there’s no way else to describe that — that is a cumulative effect of 20 years," Milley said.

The general speculated that the U.S. had trained an Afghan Army that "mirrored" the American military without taking into account local and cultural traditions and allowed it to becoe too dependent on American technology.

"We helped build a state, but we could not forge a nation," said Austin. "The fact that the Afghan army, we and our partners trained, simply melted away – in many cases without firing a shot – took us all by surprise. It would be dishonest to claim otherwise."

"We need to consider some uncomfortable truths," he added. "That we did not fully comprehend the depth of corruption and poor leadership in their senior ranks, that we did not grasp the damaging effect of frequent and unexplained rotations by President Ghani of his commanders, that we did not anticipate the snowball effect caused by the deals that Taliban commanders struck with local leaders in the wake of the Doha agreement, that the Doha agreement itself had a demoralizing effect on Afghan soldiers, and that we failed to fully grasp that there was only so much for which – and for whom – many of the Afghan forces would fight. We provided the Afghan military with equipment and aircraft and the skills to use them."

"Over the years, they often fought bravely," said Austin. "Tens of thousands of Afghan soldiers and police officers died. But in the end, we couldn’t provide them with the will to win. At least not all of them."

US intelligence did not predict the Taliban's swift takeover, the generals said

The three leaders expressed surprise at how Afghan forces had quickly fallen apart leading to a Taliban takeover of the country in 11 days.

"I did not foresee it to be days. I thought it could take months," said McKenzie, who added that he had anticipated that the Afghan military would be able to hold out against the Taliban until later this year and possibly into early next year.

"We certainly did not plan against a collapse of the government in 11 days," Austin said.

"There's no intel assessment that says the government is going to collapse and the military is going to collapse in 11 days that I'm aware of. And I've read I think all of them," said Milley, who later described the failure to predict the scope and scale of the Taliban takeover as "a swing and a miss."

Revelations in 'the book'

In his opening statement, Milley explained how his two phone calls to his counterpart in China, first described in the book "Peril" by Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Robert Costa, were authorized by then-Defense Secretary Mark Esper. Milley also said that the Trump national security team was fully briefed on the calls that were intended to reassure China that then-President Donald Trump was not planning a military attack.

"I know, I am certain, that President Trump did not intend to attack the Chinese, and it is my directed responsibility and it was my directed responsibility by the secretary, to convey that intent to the Chinese," Milley said. "My task at that time was to de-escalate my message again was consistent, stay calm, steady and de-escalate. We are not going to attack you."

He pushed back on another story in the book that, in a phone call with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi after the Jan. 6 Capitol attack, he agreed with her assessment that Trump was "crazy."

"I’m not qualified to evaluate the mental fitness or the health of a former president, present president or anybody else or anybody in this room," Milley said. "That’s not my job. That’s not what I do. And that’s not what I did."

Several Republican senators took Milley to task for giving access to reporters and authors.

“I think what you did with making time to talk to these authors, burnishing your image, kind of building that bluster, but then not putting the focus on Afghanistan and what was happening there," said Sen. Marsha Blackburn, R-Tenn. "General Milley, this is disappointing to me. I know it's disappointing to people that have served with you or under you, under your command. It does not serve our nation.”

"You’re doing these interviews and doing them in 2021. Makes me wonder the books, were you a little distracted about what was going on in Afghanistan?” said GOP Sen. Josh Hawley of Missouri who then demanded that Austin and Milley should resign.