Taliban pose threat to Afghan cultural heritage as they sweep back into power

When previously in power, the Taliban destroyed much of the Afghan culture.

When Ali Karimi was young, he had to bury his books in the backyard.

In 1996, when the Taliban first came to power after years of civil war in Afghanistan, his family feared that fighters from the strict Islamist militant group would harm their family if they found the works of fiction in Persian.

Earlier this month, Karimi, now an academic at the University of Pennsylvania, got a call from his father in Kabul, asking what to do with his Persian and English books again.

"I told him Kabul will not fall. Like everyone else, I thought the government would last for at least a couple of months. And now, they are worried, and a lot of people are burying their books," Karimi told ABC News.

It's not just literature. Taliban fighters in some cities have ordered only Islamic music be played on radio stations, the Afghan National Archives' administrative building was looted this past week and the statue to an ethnic minority leader was destroyed the very night the city was seized by Taliban forces.

Afghanistan's cultural heritage -- poetry, film, music, art, artifacts, antiquities, statues, museums and more -- are all under threat as the Taliban return to power, according to scholars and experts.

"It should really concern ... people of conscience that these types of barbaric acts should not be taking place, and we should not normalize a group that has a history of such really obscene acts of violence -- cultural violence, historical violence -- and damage to literary history and world history. This shouldn't be taken lightly at all," said Ahmad Rashid Salim, an author and academic who studies Islamic and Persian thought at the University of California, Berkeley.

That violent history was on display for five years when the Taliban ruled most of Afghanistan from 1996 until the U.S. invasion that toppled their government in 2001. During that dark period, Taliban fighters killed artists, musicians and poets; destroyed antiquities, musical instruments and audio cassettes; banned singing and burned down libraries; and let museums crumble to disrepair, destruction and looting.

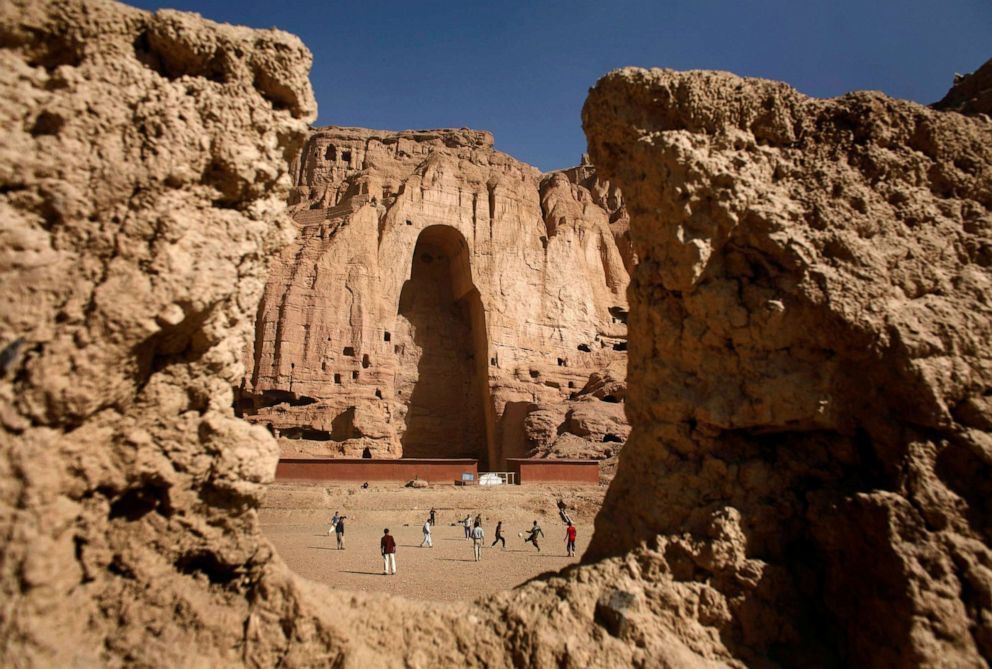

Perhaps most famously, months before the Sept. 11th attacks and the U.S. invasion, the world was horrified by a Taliban atrocity -- blowing up the Buddha statues of Bamiyan, a province in central Afghanistan. The two statues, 125-feet and 180-feet tall, dated back to the early 600s and were part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The jarring attack on world heritage sparked a global outcry. But it was also core to who the militant group is and what they believe, according to scholars.

"Right now, everything is in limbo. What's going to happen? We have a regime that did atrocious things -- they destroyed the Buddhas, they destroyed the museum, they did their best to get rid of any art with a representation of a living form. Now what are we going to do?" said Farhad Azad, founder and editor-in-chief of Afghan Magazine, who led the first U.S. cultural exchange to Afghanistan in 2002.

The loss could be all the more profound because the last 20 years has seen a renaissance in Afghan culture, reflective of the country's diversity of ethnicities and languages and fueled by its enormous population of young people. A folk music scene has flourished, playing music passed down by oral tradition; a new generation of authors, poets and filmmakers have created exciting new works; an explosion of media outlets have entrenched a vibrant, free press culture; and a surge in translation and academic study has elevated and unearthed the ancient culture of modern-day Afghanistan.

"I really lament and mourn the fact that the music industry, culture, language and poetry, and literature and material culture are going to take a hit and be damaged and severed once again from taking root and thriving within Afghanistan," said Salim.

The Taliban said in a decree last Sunday that anyone who encroached on the National Archives, the National Museum, libraries and other government facilities "will be severely punished." Some Taliban leaders reportedly visited Kabul's Archaeological Institute and directed it to continue to protect historical monuments.

"Right now, the Taliban are behaving because there are American TV cameras everywhere on the streets of Kabul, so they are putting on a show, a performance of tolerance. But things will change very soon," said Karimi. "When they establish themselves, then they start to eliminate 'threats,' and that's going to reveal their true colors."

Those true colors are rooted in a warped sense of tradition, according to Karimi, who said the militants see themselves as 'but shikan,' or idol destroyers. But Salim said it comes from a more political angle -- an effort to control the Afghan people.

"The Taliban are an armed extremist group who are rooted in the deployment of violence," Salim said. "When you kill history, when you kill language, when you kill leaders, when you kill intellectuals, when you kill the religious and spiritual leaders of a society, you can do whatever you want with the people who no longer have a past."

A State Department spokesperson told ABC News they "acknowledge" the Taliban's stated commitment to "protect Afghanistan's rich cultural heritage, but as with all statements from the Taliban, we will be watching closely to see whether they match actions to words."

In certain cities, far from the cameras in Kabul, those actions have already unfolded -- demonstrating to many Afghans that behind their social media savvy and public relations statements, they largely have not changed.

The night after Taliban fighters secured Bamiyan, a provincial capital west of Kabul, the statue of Abdul Ali Mazari was destroyed. Mazari was a Hazara leader, an ethnic minority group that the Taliban, ISIS and past Afghan rulers have repeatedly targeted with brutal violence. In 1995, Mazari himself was lured by the Taliban to negotiations, where he was murdered -- his body tossed from a helicopter.

"Just go back three weeks to see what the Taliban inflicted upon the Afghan civilian population," said Salim, including the assassinations earlier this month of a popular comedian known as Khasha Zwan and poet and historian Abdullah Atefi.

As Kabul fell to Taliban forces on Aug. 15, the National Archives' administrative building was also looted, its director Rahbeen Meerza said in a Facebook post. It's unclear who is responsible, and Meerza asked the Taliban for help -- as did the National Museum of Afghanistan.

Karimi, who started his research at the Archives, said he feared for the institution's precious collection, including ancient manuscripts from Islamic and Persian scholars, many of which are just being studied and translated now. Now, some of his former colleagues are deactivating their social media accounts or deleting old posts to self-censor, he said.

It's reminiscent of how archivists and academics put antiquities in hiding as the Taliban came to power in 1996, stowing artifacts away in the Archives' secret vault or in their homes around the country. Even still, thousands of pieces of pottery, coins, paintings and more were destroyed, damaged, stolen and looted, said Salim.

One thing that may not change is the use of film and photography, which were once banned -- if only because the Taliban have weaponized both for themselves, said Karimi.

"They are themselves visual artists right now. They know how to use images to project power, scare people, to win hearts and minds. Because of that, I think they will not ban photography and videography, but other aspects of art and culture are very much in danger," he added.

Already, many of Afghanistan's artists and scholars are feeling that danger and pleading for help.

"After twenty years of immense gains for our country and especially our younger generations, all could be lost again in this abandonment," Sahraa Karimi, an Afghan filmmaker and the first woman to lead the Afghan Film Organization, wrote in an open letter just two days before Kabul's fall.

"Everything that I have worked so hard to build as a filmmaker in my country is at risk of falling. If the Taliban take over they will ban all art. I and other filmmakers could be next on their hit list," she added.

While Karimi was able to flee this week, others have gone into hiding.

"I am worried about my children's future if they kill me. In the last few days, I have not left my house. I don't know when I can because it is getting dangerous by the day," said an Afghan artist, whose identity ABC News is protecting, with three children who has worked with a theater company, bringing live theater to rural villages. Three Afghan American artists started a GoFundMe page to support them and others on the run from the Taliban.

In meetings with the Taliban leadership in Qatar, U.S. envoy Zalmay Khalilzad has "consistently emphasized the importance of human rights and fundamental freedoms," including freedom of expression and respect for women, girls and minorities, the State Department spokesperson told ABC News.

"The Taliban is fully aware of the standards they must meet for a future Afghanistan and its government to be accepted into the international community, including preservation of cultural heritage," they added, calling their past destruction "an irreplaceable loss to the people of Afghanistan and to the global community."

UNESCO issued a similar statement Thursday, saying it is "closely following the situation on the ground and is committed to exercising all possible efforts to safeguard the invaluable cultural heritage of Afghanistan."

But with more atrocities reported day by day, especially from territory far outside Kabul, it's unclear what efforts the international community is willing to commit.

In the meantime, it seems, it will be up to the Afghan people to defend their cultural heritage on behalf of the world -- armed with cellphones, social media and an invigorated national identity.

"The Afghans in Afghanistan have built an immense, nationalistic identity that was always there, but it was fortified in the last 20 years," said Azad, adding that now, "Everyone has a device. It's not the same country."

That resistance is already evident in Kabul, Jalalabad, Asadabad and other cities where protesters on Wednesday and especially Thursday -- Afghanistan's independence day -- waved the black, red and green of Afghanistan's national flag -- and in many cases were met with violent crackdowns by Afghan forces.

"The Taliban have the capacity and they definitely have the will and the history of employing violence to silence the population," Salim said. "At the end of the day, as brave and as resilient and as strong as the Afghan people are, they are human beings. They are regular human beings who want to protect their lives."

Protecting your life and your family now means burying books or destroying CDs. Karimi said his friends have sent photos of cassettes and CDs destroyed and dumped in garbage piles -- a sign of fear for music the Taliban doesn't approve.

"A country without music is a dark place," he added.