Moore's Law: What's in Store For the Next 50 Years of Computing Power

Can theory explaining why computers get faster, cheaper continue to hold true?

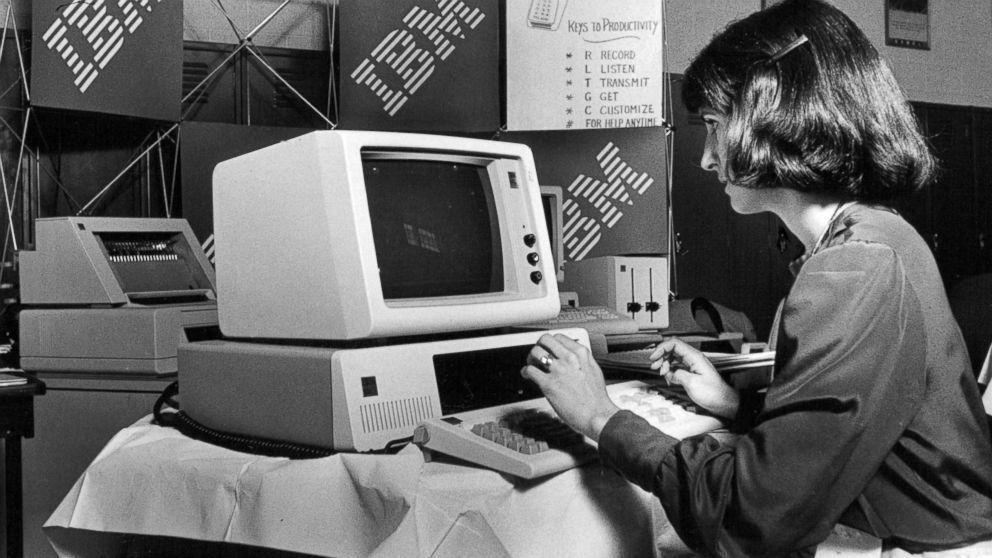

— -- Moore's Law, the golden rule of the electronics industry that explains how computers will continue to get faster and cheaper, helped bring about the advent of personal computing and smartphones.

The guiding rule in the computing world that helped bring technology into our everyday lives turned 50 years old on Sunday -- but it may be reaching its edge.

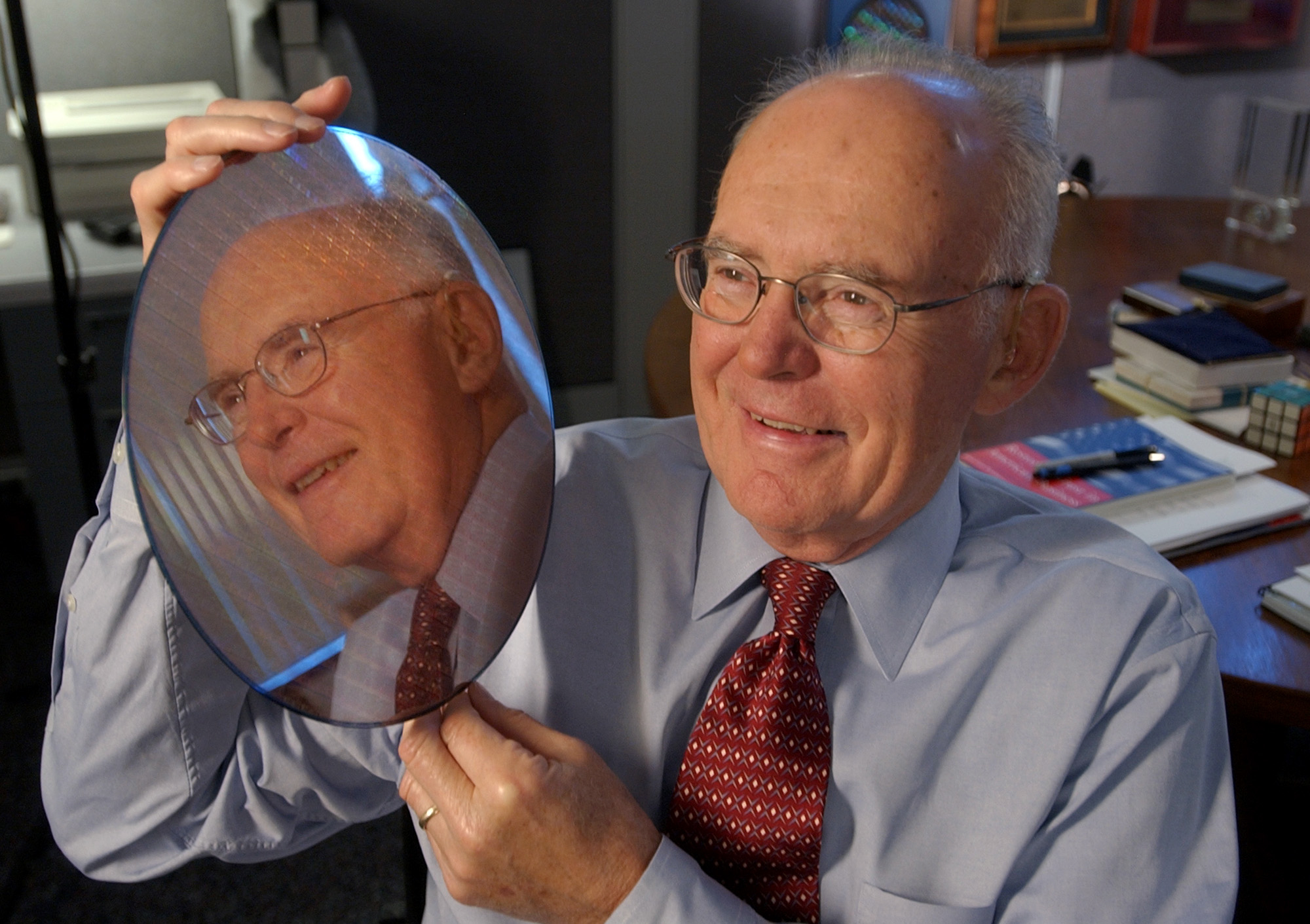

In 1965, Gordon Moore, a co-founder of Intel, predicted that the number of tiny electrical switches that could be placed on a computer chip, called transistors, would double approximately every two years.

That has largely held true -- look no further than the computers, cameras, phones and music players that are now condensed into a single smartphone.

In an interview with IEEE Spectrum last month, Moore said he's been amazed at "how creative the engineers have been in finding ways around what we thought were going to be pretty hard stops."

However he said "now we're getting to the point where it's more and more difficult, and some of the laws are quite fundamental."

In 2013, Robert Colwell, a former Intel electrical engineer, predicted Moore's law would be dead within a decade due to the difficulty of shrinking transistors beyond a certain point to fit more on a chip.

Colwell said it would be difficult to shrink the transistor density beyond either 7nm or 5nm (a unit measuring one billionth of a meter.)

"We will play all the little tricks that we still didn't get around to," he said, according to the BBC. "We'll make better machines for a while, but you can't fix [the loss of] that exponential. A bunch of incremental tweaks isn't going to hack it."