Facing racism: Activists in Arkansas chase down KKK leader with BBQ and a protest

"Food automatically creates a common ground."

This report is part of "Turning Point," a groundbreaking series by ABC News examining the racial reckoning sweeping the United States and exploring whether it can lead to lasting reconciliation.

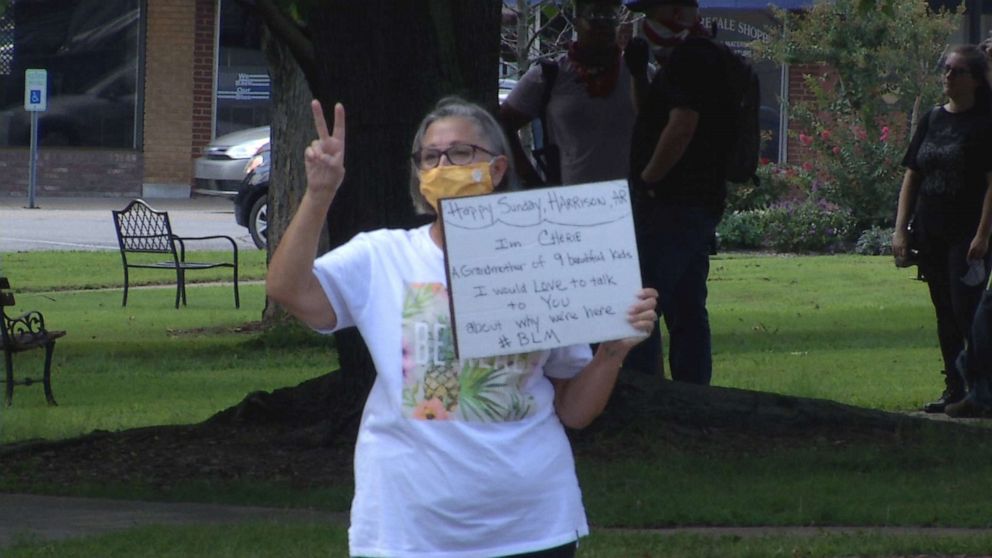

It was on a hot summer Sunday earlier this year when activists waving Black Lives Matter flags arrived in one of the whitest communities in the United States.

They were there to demonstrate, but also to hold a cookout for which they invited the residents of Harrison, Arkansas, to grab some lunch and engage in a discussion. They were largely unwelcome. People driving by waved Confederate flags and held up their middle fingers. With the Ku Klux Klan headquarters just a couple miles down the road, racists had already installed their snipers on the rooftops in the city’s downtown area.

Activist Aaron Clarke said he was there to meet white people, who he believes don't understand the protests that have spanned the country or the culture of the people who many local residents have likely only seen on their television screens. On that Sunday, he was concerned the situation would turn violent.

"I received hundreds ... of death threats before we went down to that barbecue," he told "Nightline." "They said, 'I got a rifle for you down here, monkey.' All sorts of things."

Having the cookout was Clarke's idea. His thought process: "Food automatically creates a common ground, and then we can figure out more common ground from there. But from the jump, we all have a common ground because I'm pretty sure everybody likes to eat."

Harrison used to be known as a "sundown town," where Black Americans faced the threat of death if they were outside after dusk.

Soon after the activists arrived, a militia did too. One of its members said his group was neither affiliated with the KKK nor racist, but that they wanted to stop the activists from "burning buildings and hurting innocent people."

"We don't want that to happen," said one of the militia members, dressed in a mask and brown fatigues. "So, if we can keep it out of our area in Arkansas, that's what we want to do."

With tensions beginning to rise, Clarke started recording on Facebook Live. During the livestream, he invited others from across Boone County to come visit.

"Let's talk," he said in the video. "I'm willing to meet anybody. We can go get a beer or something. We can sit down and talk and we can be adults."

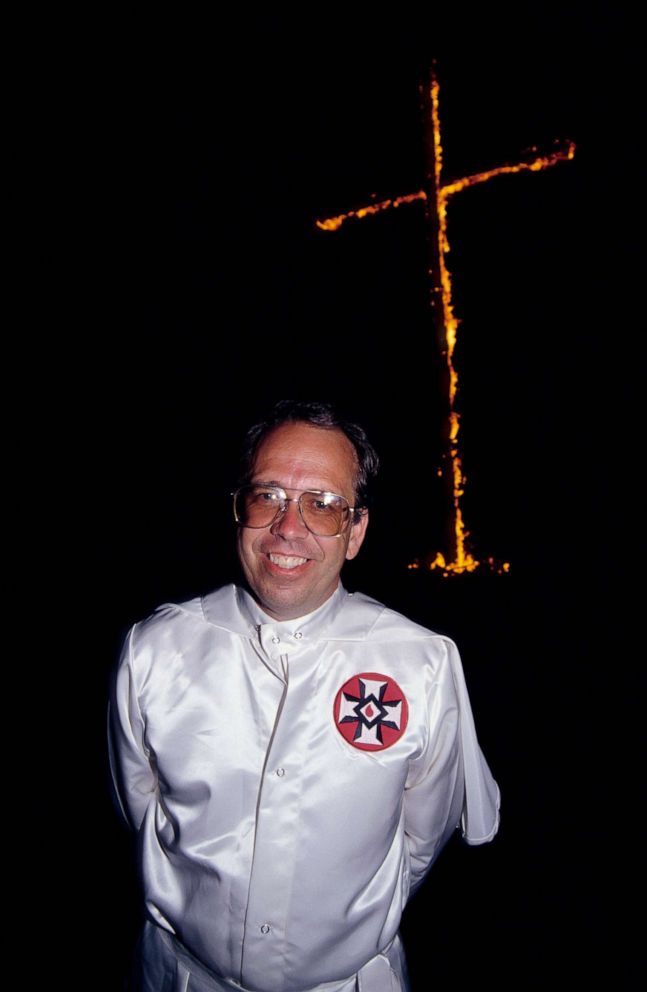

At one point, he heard that Thomas Robb, a pastor at the nearby Christian Revival Center and the national director of the KKK, was planning to come by. Robb, 74, has been leading the hate group since the 1980s, when former grand wizard David Duke stepped down.

Clarke and his group had attempted to meet with the hate group leader earlier this summer. They tried to bring their cookout to Robb's front door, but were stopped by authorities, and had to settle for a nearby fire station instead.

Clarke, whose group is called Bridge The Gap, said he'd "definitely" like to have a discussion with Robb.

"I would try to listen to what he had to say about what his organization is," Clarke said. "What do you feel about us? Why do you hate us? Like, I have questions to ask. ... Do I think I would change him or make him any different? No. But I feel like sometimes you have to make people face their own resolve. You have to make them face their own demons. You have to make them question themselves. And you can't do that if you don't talk to them."

"You can't make them challenge their own thought process and their own way of thinking if you just let them continue to think that way and let it go unchallenged," he added. "So I want to go and I want to challenge this way of thinking."

Jessica Angelica, another activist working with Clarke, said she would also be up for a conversation with Robb.

"Come talk to us. Come meet me. Come shake my hand. Come see for yourself that I am not anti-American," Angelica told "Nightline." "I am not hate-filled. I'm not a terrorist. I love my community and I want the best for all of us. Aaron and I do this because we want a better life for our children."

Clarke said that one thing he learned while trying to reach out to some of these local residents is that they "don't really know anything about people of color."

"So what we want to do -- and [it's] our mission -- is to go against the narrative," he said. "We want to come and say ... 'Come meet us.'"

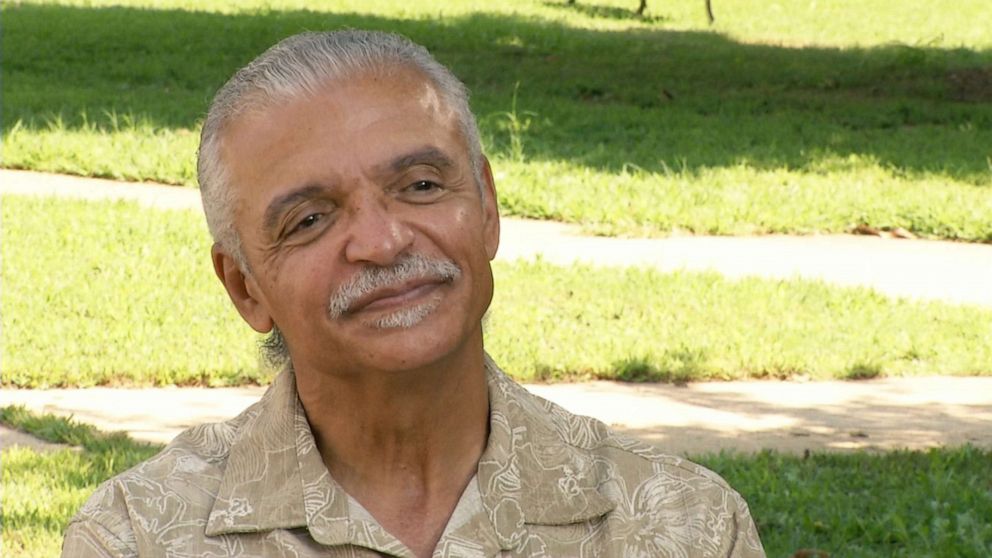

Clarke's cookout is one of the latest efforts in the region to make it more welcoming to people of color. Kevin Cheri, a retired superintendent for the National Park Service's Buffalo National River, was one of the first Black residents in Harrison when he moved there in the 1970s. He said it wasn't always easy living there and that he's since joined a local government task force dedicated to repairing the city's image.

"We've got to get people to be willing to be uncomfortable," he said of his efforts. "They've got to be willing to to learn and find out what they don't know."

Cheri underlined that there are many communities across the country that have more in common with Harrison, and Boone County, than they might think. He said there are cities big and small where residents haven't done enough to truly know their neighbors who are of other races and ethnicities.

"When I'm able to share my experiences with people ... especially now they know me, they're comfortable with me, and all of a sudden, the issue of the Confederate flag comes up, and I could tell them, 'Look, you have to understand that in my life, when I see that flag, there's a certain level of fear that exists because growing up in New Orleans, if you saw a car coming down the street with the flag, you got out of the way. You hid. You were ready. Because it could be trouble.'"

"We also knew that wherever there was a lynching, that flag was present," he added.

He went on to speak about some of the racist experiences that he and his family went through, such as his sisters being pelted with eggs by white people driving by. He also shared his memories of police officers who pulled guns on him, in front of his own home, after a nearby store was robbed by Black suspects.

"When people hear that stuff happened to me, it's like 'Wow.' Now it's a different meaning to them because, well, this is Kevin, our friend,'" he said. "Then they're more willing to believe what you're saying. But either way, we have to talk and we as Blacks also have to be willing to listen because we have to understand their backgrounds and where they're coming from, too."

But just coming together can be a lot harder than it might seem.

In an interview with the Kansas City Star, KKK leader Thomas Robb made the case that "Blacks by their nature probably prefer being around other Blacks because they can relate to them. There's always gonna be some that's gonna want to go hang out with the white group. But by the whole, people prefer being around their own kind, and there's nothing wrong with that."

Researchers say that Americans confirm this belief through their actions.

Kristine Ajrouch, a professor of sociology, anthropology and criminology at Eastern Michigan University, said that her research on the ethnicity of people's networks in the metro-Detroit area showed that most people gravitated toward people who are the same race or ethnicity.

"We specifically asked them whether or not the person that they identified as close and important to them is of the same race and/or ethnicity as them, and what we found is that for both whites and Blacks ... over 95% of their networks are comprised of the same race," she said.

Ajrouch, who is of Middle Eastern descent, said it's not just personal relationships that may determine these outcomes, though.

"I think the larger media and societal portrayals of these groups also play a big role in how we understand people who are different than us because they immediately shape how we're gonna react to the person we're coming into contact with," she said.

ABC News correspondent Steve Osunsami asked Ajrouch about friendships on social media.

"When I look at the Facebook pages of some of my white friends, even people who are supportive of Black Lives Matter, I can look through sometimes years and decades of photos and not see that person standing next to anybody who looks like me," said Osunsami.

"And it's stunning to me," he added. "We have so many people who want to change things, who live their lives in a way that doesn't translate, does that make sense?"

"Yes, it makes a lot of sense," said Ajrouch. "You know, I think I'm not surprised that when you look at Facebook posts, you tend to see it to be of the same race as the person who you're looking at. Because I think there's been a lot of research to show that for the most part, people's social networks are very homogenous when it comes to race and ethnicity."

Ajrouch said that there are a number of different reasons why people tend to maintain social networks that are of their own race. For people of color, it can feel tiring to teach white friends about the Black experience, for example. For white Americans, the sheer difference in numbers makes it harder to have Black and brown friends in their circles.

"White Americans are still numerically the majority and the opportunities that they have to come in contact with people who are different than them are just far fewer," she said. "They don't have to interact with people who are different than them in order to have opportunities, whereas individuals who are of racial or ethnic minority groups, they have to."

In some ways, the activists who showed up in Harrison earlier this summer were successful with their outreach: Clarke was able to develop a mutual understanding with the militia members he spoke to, and at the end of it all, not a shot was fired or a punch thrown.

But also, the national director of the Ku Klux Klan never appeared.