For foster kids, COVID-19 poses a second obstacle to stability and success

An estimated 400,000 children are in foster care in the U.S.

Millions of girls are inspired by Beyonce’s music. But for 15-year-old Azaria Jackson, the lyrics to the song “Irreplaceable” are especially personal and have helped her remain resilient through her hardest times.

“To the left, to the left, everything you own in the box to the left… Don’t you ever for a second get to thinking you’re irreplaceable,” she sings.

“It just inspires me to not think that it's your fault always,” Jackson said. “If someone leaves or [someone] talks about you or mistreats you in some type of way, just stay strong, keep your head up, and better days will come. And you'll find someone else. I feel like people should be more open-minded that it's not the kid's fault that they're in foster care.”

For the last five years, Jackson has been in the foster system in the Los Angeles area after her single mom became unable to financially support her and her siblings. When she first entered the system, she said she was “confused and shocked.”

“It took me a while to adjust... Like, look, you're in the foster system, you have to adjust with their rules -- what they say -- and not my mom,” she said. “I was scared. Some nights I would actually cry because I miss my mom and my brothers. It was just different, and at that time, I literally would just pray.”

This year, she found a family in her caregiver, Ornetta Lupper. She’s been providing Jackson with her ninth foster home in five years. But it’s hard to beat the real thing; Jackson is part of a set of triplets and the coronavirus pandemic made it even harder to see her siblings.

“It's challenging for the children that are not in stable placements right now, and the moving,” Lupper said. “I get a lot of calls asking if I have room, and I do not. Also, with visitation, if they have visitation with parents and stuff like that, it all came to a halt during the COVID season. So, now ... it's up in the air.”

Jackson is one of an estimated 400,000 foster children living in the United States, 56% of whom are Black, Latino or part of another minority group -- all of which have been hit hard by the pandemic.

Lyndsey Collins is the president of First Star, a nonprofit that, for the past decade, has focused on creating and offering support systems that help propel foster children like Jackson into higher education.

“Young people in care who are Black or brown are already facing, some might say, insurmountable challenges and obstacles in order to transition into successful early adulthood,” Collins said. “Then when we couple that with the pandemic and the realities that the virus is impacting Black and brown communities to a higher degree than other communities ... it's a reality that we have to be … thoughtful around A) understanding and … B) taking action.”

Jackson said other people don’t understand how hard it is to be a foster kid because of the stigma that surrounds that moniker.

“At school, I do not say, ‘I'm a foster kid,’” Jackson said. “I relate to my foster families as brothers and sisters, mom and dad, because I feel it's uncomfortable how people stereotype foster children like they're not like other children.”

Now, as the country braces for another surge of COVID-19 cases, some of the most vulnerable are being forced to survive largely on their own.

“During COVID, I recently started journaling, especially since I don't see my brothers as much nor my mom,” Jackson said. “I'd be writing in there about my family. And what I hope in the future and that they're all safe.”

Thousands of foster kids around the country have been facing the brunt of a harsh new reality, in a society frozen by the coronavirus. Family courts have been shut down. Visitations have been suspended. And there are fears about spikes in abuse.

“If we think about the time frame now that we've been experiencing this pandemic, that's about eight months,” Collins said. “There is this sense of increased anxiety happening among many youths in the system, especially your teenagers in care. They see the pandemic and the issues within the political atmosphere as triggering, and what this does is it brings up past childhood traumas and, as a result of that, some of our young people are sort of stymied.”

Collins urged everyone to “be kind” to young people in the foster care system.

“They are not in the system because they have committed a bad act,” she said, adding that sometimes they are in the foster system because their parents lost their job and can’t support them.

Jackson said she’s been trying to make the best of it.

“You just gotta hope for the best," Jackson said. “Me, just praying and doing what I have to do -- getting good grades, staying focused and having good behavior was just one thing I just had to just teach myself, and just keep doing it.”

As millions of kids across the country have difficulties with online learning during the pandemic, many underprivileged kids are struggling with basic access to technology, forcing students like Jackson to take matters into their own hands.

“I advocated for a laptop because I knew I would need one, but at the time, I didn't have,” she said. “So I made sure I told my social worker and I emailed my attorney, too.”

“I feel like it's unfair for the kids, like homeless kids and youth, that aren't able to have access to internet or a device,” Jackson continued. “I feel like, schools, if the kid is homeless or foster youth, they should give out [a] free hotspot and a Chromebook that they could use for the school year.”

Collins agrees kids in the system are affected disproportionately by learning loss because of their “inability to access school.”

Across the country, in Camden, New Jersey, 17-year-old Maryori Hernandez is also trying to learn while navigating the foster care system.

“I'm a student. I like to be more hands-on,” Hernandez said. “I talk to the teacher about problems that I don’t understand. … That was tough on me. When I didn't understand an assignment, I used to get really stressed.”

She says only a few people in her life know that she’s in foster care.

“I don't tell many people my situation, I only tell a few who are really close to me,” she said. “For others, I'm just a normal kid going to school. Just with regular problems.”

Hernandez was 11 when she and her three sisters were separated after their mom’s arrest.

“They didn't tell me anything... It was actually just me and my two little sisters at the house,” Hernandez remembered. “They came in and they were like, ‘We need you guys to come with us,’ and I was like, ‘OK.’ I didn’t understand anything. I kind of just followed and I took my sisters and then I basically didn't get told anything. ”

Hernandez’s family is from Honduras and no one is an American citizen. Six years ago, Hernandez’s mother was arrested and eventually deported, forcing Hernandez and her sisters into the foster system.

“I got removed and I got put into foster care. At the beginning, me and my sisters were separated for a few weeks and then we came back to another foster house,” Hernandez said. “We were there for two years. The four of us together, we searched a couple of families to adopt us. But it never worked out. And then my two younger ones got adopted. And me and my big sister didn’t.”

Hernandez has spent the past six years in five houses.

“It was tough. I don't like moving,” she said. “I hate it because it's like you get used to people, you get used to school, to friends, and then they just come out of nowhere and are like, ‘OK, you're moving for a couple of years.’”

Hernandez and her older sister, Jennifer, have been working to find a forever home together, and in 2017, the sisters learned that a family wanted to adopt them. Since then, however, immigration laws and regulations had slowed down the process, and then the pandemic essentially placed it on hold.

“I had been working [on] getting adopted with this family, and... everything just slowed down because of COVID,” she said. “So my green card, my social work number, it got slowed down. So now I'm just like waiting for it.”

For these youth, the one thing they crave is the one thing they don’t have: stability.

“I want to be a regular teenager -- get my driver's license, drive, work, just go out whenever I want type of thing,” Hernandez said. “That’s been tough because I see my friends and they're like, ‘I'm driving now’ … I want to drive now.”

Through the years of uncertainty, Hernandez points to her big sister as her rock.

“I feel like everybody sees us as like, ‘Oh, you're in foster care. You've been through a lot,’” Hernandez said. “They don’t actually know what my sister's been through. She’s been through way worse than me, and the fact that she just walks around and smiles and makes you smile … I don’t know, I enjoy that from her -- that she's happy.”

Despite her positive outlook, Hernandez wants people to know that there are scars we don’t see.

“Kids really get lonely and [adults] don't notice because kids know how to hide it,” she said. “But kids get lonely... They need that support. For you to tell them every once in a while [that] you love them, you're there for them.”

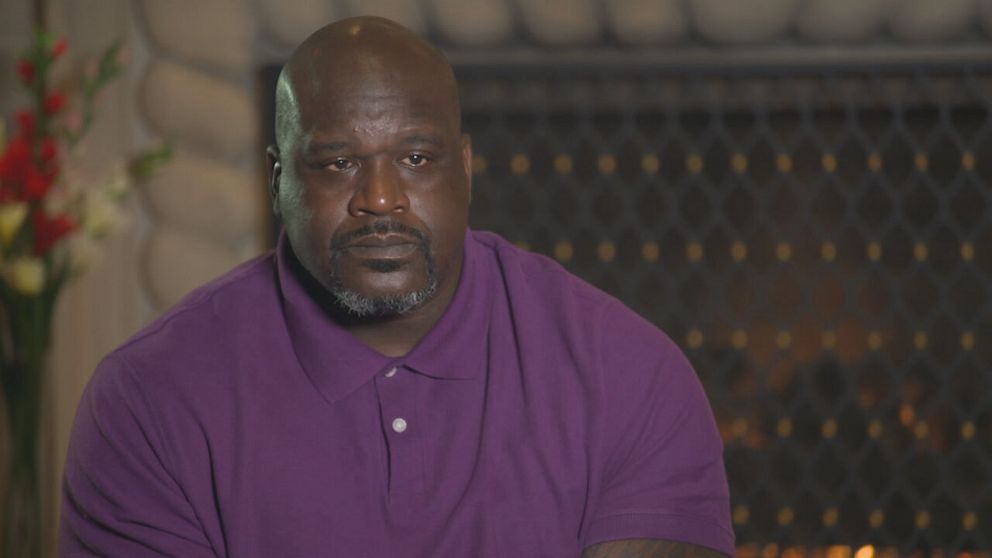

NBA star Shaquille O’Neal has become an active advocate for kids like Hernandez and Jackson, spreading awareness of the issues children in the foster care system face.

“I've always had my mom and dad. What if I didn't?” O’Neal said. “How does that feel? If we can bring awareness to the situation and try to help them make change, that's what I'm always about. When I say I'm lucky, [it] could’ve been me.”

O’Neal is the executive producer of “Foster Boy,” with director Peter Samuelson, the co-founder of First Star. The film which tells the fictional story of Jamal, a man who gets imprisoned after years of abuse in the foster system.

“All the stories hurt my heart. They shouldn't happen,” he said. “That could mess with you mentally for the rest of your life, and that doesn't need to happen. Like, when a person's down, what's below bottom? A lot of people don't come back from that.”

Hernandez says that it’s the hope that she’ll get through this period of her life that keeps her going through.

“Maybe because I have hopes that in my future, I'll be good,” she said. “This is just a little obstacle that I have. I'll get through it and I'll be who I want to be when I get older. This is not gonna stop me.”

With only a year-and-a-half left in high school, Hernandez has big dreams for what’s ahead.

“When I picture my future, I see myself as a lawyer,” she said. “I think I want to go for immigration law, because [of] all I've been through, I would love to help other people like that. Or, an actress. I would definitely love to be an actress, and just be out there.”

If there’s one word to describe kids like Hernandez and Jackson, it’s “unflappable.”

“When I think of myself in 10 years, I see me already starting my career,” Jackson said. “Doing good, focusing on my job and friends and family, and seeing my baby brother grow up and my nephew.”

Jackson was recently able to return to living with her biological mom, a dream she has had for years.

“I feel like there should be more awareness about foster youth and foster care,” she said. “Not every foster child is gonna go through a good experience like I've been through.”

Now, as the two take steps to figuring out young adulthood, they’re both focused on giving back.

“I would love to help anybody in any kind of way, to be honest, especially kids who go into foster care like me, because it doesn't stop with me,” Hernandez said. “It's like there's more coming. Like in my future, if it was possible, if I have a good life. I will be, I would love to to be a foster parent, to be honest. And just help kids.”