'You weren't able to grill him': Investigator says it was 'implied' not to push Ted Kennedy 'too hard' on Chappaquiddick

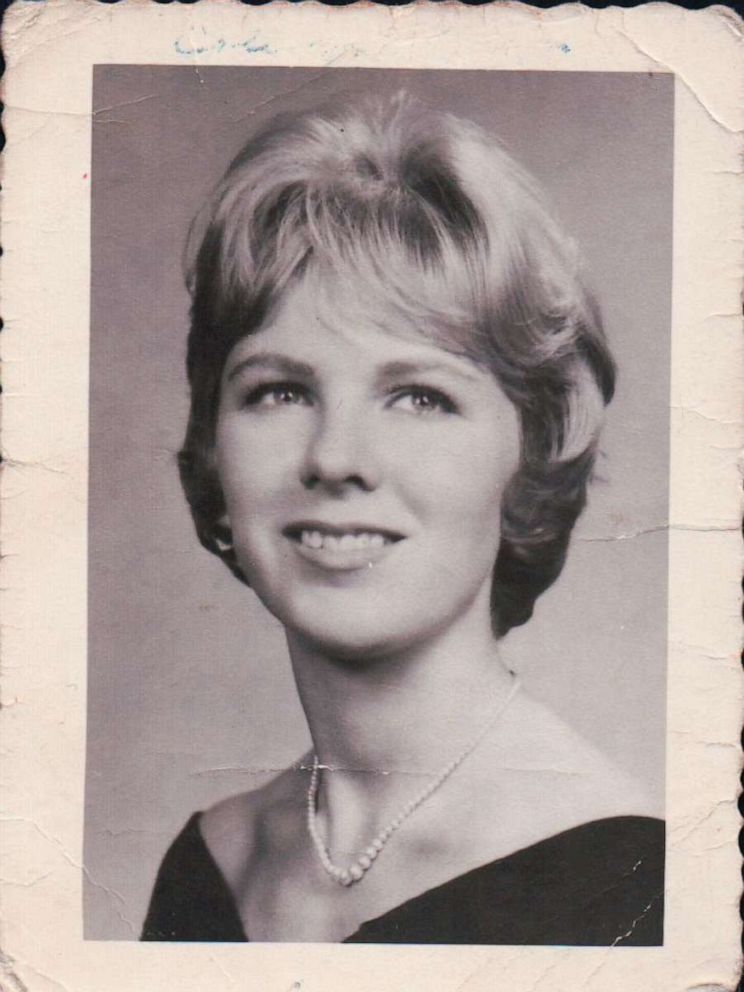

Mary Jo Kopechne died in July 1969 after Ted Kennedy's car drove off a bridge.

On the night of July 18, 1969, a group of women known as the Boiler Room Girls, who had worked for Robert F. Kennedy’s 1968 presidential campaign before his assassination, gathered for a reunion on the island of Chappaquiddick near Martha’s Vineyard, off the coast of Massachusetts. For one of those women, Mary Jo Kopechne, it would be her last night alive.

According to some of the people who knew her and those familiar with the case, however, Kopechne would not receive the attention she deserved following her death. Instead, that attention would go to the late Senator Ted Kennedy, who hosted the reunion for his brother’s former staffers.

On that night, after reportedly growing tired, Kopechne hitched a ride with Kennedy back to the Katama Shores Motel, where she was staying. But she would never make it back to her hotel when he drove his car off a bridge, causing it to flip upside-down and trapping her inside.

The details of the incident are murky. Kennedy managed to escape the overturned vehicle, but it’s unclear what exactly happened to Kopechne and why she too wasn’t able to escape. Ted Kennedy didn’t report the incident until hours later, claiming that he was in a state of shock and exhaustion.

Watch the full story of "The Girl in the Car" tonight, May 7 at 10 p.m. ET on ABC.

"I remember thinking as the cold water rushed in around my head that I was for certain drowning. Then water entered my lungs and I actually felt the sensation of drowning, but somehow I struggled to the surface alive," Kennedy said during a televised address a week after Kopechne’s death. "I made immediate and repeated efforts to save Mary Jo...but succeeded [in] only increasing my state of utter exhaustion and alarm."

In the morning hours after the car went off the bridge, police and fire search and rescue teams recovered Kopechne’s body and investigated the scene. John Farrar, a former captain of the search and rescue division of the Edgartown Fire Department, said that based on the position of Kopechne’s body in the overturned car, he suspected that she died from suffocation -- not drowning -- after running out of oxygen in a pocket of air.

Farrar said that it’s possible Kopechne could’ve survived if Kennedy notified authorities as soon as the accident occurred.

"Since he had plenty of time to get help, why didn’t he get help? Might’ve saved her life," Farrar said.

But Kennedy was nowhere near the scene; he was having coffee with friends at the Shiretown Inn, according to Liz McNeil, host of People magazine’s "Cover-Up" podcast, who said that after speaking to two attorneys, he finally notified authorities.

However, when Kennedy went into the police station for questioning, "it was implied without direct words that we were not...not to push him too hard. Show Senator Kennedy the respect of a senator," said Bob Molla, a former investigating officer for the Registry of Motor Vehicles.

"You weren’t going to be able to grill him," Molla added, only "ask your questions, he’ll give you an answer and take it at that."

As time progressed, other questions about Kopechne’s death began to emerge.

President Richard Nixon, who had just won an election and saw Kennedy as a threat to a second term, asked an investigator to look into the case.

He discovered that Kennedy had made several calls in the hours following the accident. Then, during Kopechne’s funeral, Kennedy showed up wearing a neck brace -- one that he hadn’t been wearing in the time leading up to his appearance, McNeil said.

"It leads many to ask questions about his injuries, whether he had injuries -- could this be some attempt at sympathy?" McNeil said.

Kennedy was later charged with leaving the scene of an accident. He pleaded guilty and received a two-month suspended sentence.

Months later, in January 1970, an official inquest was held, and many of the people who attended the reunion on the night Kopechne died appeared for questioning. Farrar, who drew an image of how Kopechne could have suffocated, said he was denied the opportunity to explain how it could’ve happened. Molla said he was subpoenaed to the inquest, but then ushered out of the courtroom.

When a grand jury was called in after the nearly four-day-long inquest, it failed to turn out an indictment. Leslie Leland, the jury foreman, spoke about how the jury was stymied in its efforts to review evidence.

"A grand jury should be able to subpoena witnesses, look at transcripts," Leland said. "If we were allowed to see the inquest material, I’m positive the grand jury would have brought back an indictment."

Bill Nelson, Kopechne’s cousin, says "the whole system was manipulated."

"A girl died that night in his car due to negligence," he added. "After they settled the grand jury, [Ted Kennedy] didn’t have to say anything more."

And through it all, Nelson said, the public fascination with Chappaquiddick was never really about Kopechne -- who was described as a sweet, kind woman who cared about civil rights, and the first in her family to go to college to seek a career at a time when few women did.

"Mary Jo, unfortunately, ended up being a footnote in her own death," Nelson said.

McNeil pointed out that a headline from the New York Daily News at the time said, "Teddy Escapes, Blonde Drowns," and said it "almost sums up" how she was characterized in the aftermath of the accident.

Elly Kluge, a friend of Kopechne’s, said it was this headline that motivated her to speak out. She said Kopechne was not just the 28-year-old blonde ex-secretary of Robert Kennedy. "She was a solid human being," she said, "with good values -- moral, ethical [and] devoted to the betterment of society."