Lawyers claim anti-malaria drug to blame in US soldier's Afghan massacre

An Army soldier was convicted of killing 16 Afghan men, women and children.

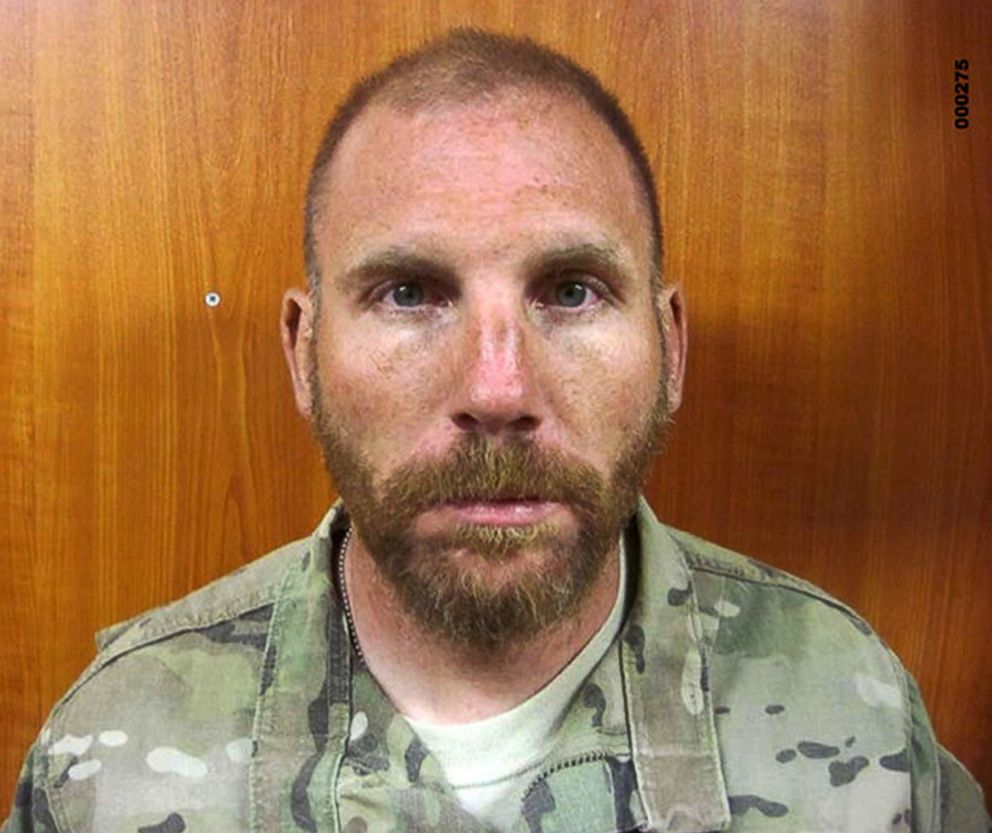

Lawyers for former Army Staff Sgt. Robert Bales are asking the U.S. Supreme Court to consider that the malaria drug mefloquine may have played a role in Bales' murder of 16 Afghan civilians during his deployment.

On March 11, 2012, Bales was on his fourth combat tour stationed in Panjwai District of Kandahar Provence, Afghanistan when he left his post and killed 16 Afghans, including women and children, in two nearby villages.

In August, 2013, Bales was sentenced to life without parole by a military jury.

Hamid Karzai, president of Afghanistan at the time, suggested the U.S. should try and hang Bales.

At the time, the soldier was taking medication to prevent malaria called mefloquine, which his lawyers argue contributed to his behavior that night. They are now petitioning the Supreme Court to review the case, saying government prosecutors did not disclose that Bales was ordered to take the drug before and during his deployment.

Court records show that after Bales' first deployment to Iraq in 2004 he complained of memory impairment and depression. And after later deployments, he complained about insomnia, irritability, anger, decreased ability to concentrate, and memory impairment.

During those deployments, Bales was taking mefloquine, but it was never recorded in his medical records.

Mefloquine, developed by the Army in the 1970s, has long been linked to disturbing neurological and psychiatric side effects.

In July 2013, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) even revised its warning label for the drug, saying rare but sometimes permanent side effects include "dizziness, loss of balance, and ringing in the ears," as well as "feeling anxious, mistrustful, depressed, or having hallucinations."

Still, the FDA approved mefloquine for the prevention and treatment of malaria.

Shortly after that update, the Department of Defense said its policy for the drug was consistent with the FDA. Several months earlier in April, Dr. Jonathan Woodson, assistant secretary of defense for health affairs, ordered mefloquine to be used as a last resort if four other malaria drugs didn't work.

Questions swirl around mefloquine

The drug was most famously investigated after four soldiers from Fort Bragg killed their wives in 2002.

Two of the men later committed suicide before standing trial. But a military panel found the drug was an "unlikely" factor in the murders.

In 2003, CBS News chronicled the story of an American couple, Dr. Robert Daehler and his wife Jane, who took the brand name drug for mefloquine called Lariam before vacationing in Kenya.

While on safari, Jane "became completely psychotic" in the van, Robert said. Once back in the United States, doctors diagnosed her with "Lariam-induced psychosis," and she spent a month in a psychiatric hospital.

Drugmaker Roche told CBS at the time that no prescription drug is free of side effects and that there's no way for a physician to predict every person at risk for psychiatric side effects.

A CNN and United Press International (UPI) investigation in 2004 looked into the suicides of three Special Forces soldiers who had all taken the drug.

"None appears to have had acute marital problems, combat stress or other personal issues that would help explain their sudden plunge into violence," UPI said in a report.