Lingering questions as Maui wildfire response faces criticism

"There is no easy answer in the heat of the battle," one fire expert said.

As the death toll continues to rise nearly two weeks after destructive wildfires tore through western Maui, the response to the crisis has come under scrutiny.

More than 110 people have been killed in the disaster, marking the deadliest wildfire in the U.S. in over 100 years.

Amid criticism, Gov. Josh Green addressed a perceived lack of trust in officials in the wake of the devastating fires.

"Do mistakes happen? Absolutely, in a crisis circumstance," Green said during a Wednesday press briefing, noting they started a "comprehensive review within 72 hours."

Hawaii Attorney General Anne Lopez said an outside organization will investigate the state and county preparation, and response to the Maui wildfires. The review will "ensure that all aspects of the incident, including any potential shortcomings in preparation, response and communication are thoroughly examined," Hawaii state Sen. Jarrett Keohokalole said in a statement.

The review is expected to take months, Lopez said.

As the details of the response are being investigated, emergency response and fire experts told ABC News there are still unanswered questions in the response. The tragedy shows how crucial timely alerts are when being threatened by fast-moving, destructive fires -- and also how challenging it can be to get information to people quickly enough and for them to respond appropriately in a chaotic situation.

"We still don't have all the story, but I can tell you from experience -- there is no easy answer in the heat of the battle," Christopher Dicus, a professor of wildland fire and fuels management at California Polytechnic State University, told ABC News.

'Like a freight train'

Dicus said he evacuated in the Creek Fire in 2020, one of the largest wildfires in California history.

"It was only my experience of being on fires in a lot of different places that told me that I needed to get out now," he said. "We got out within about 30 minutes before the fire crossed the only road getting off the mountain."

Hawaii officials said the fire that ripped through Lahaina on Aug. 8 spread one mile every minute. It traveled so quickly that there was little chance for those fleeing to outrun it, an official with the Federal Emergency Management Agency told ABC News.

"This fire was moving like a freight train," John Mills, an agency spokesperson, told ABC News' Whit Johnson on "Good Morning America" on Friday.

Sarah DeYoung, a core faculty member in the University of Delaware's Disaster Research Center, told ABC News wildfires are especially dangerous because they can be so fast-moving.

"I've deployed for many different kinds of disasters -- hurricanes, lava flows, wildfires, tornadoes, earthquakes -- and wildfires, in my opinion from everything I've seen when I deploy, are so dangerous because they are so fast-moving and they can be so catastrophic," she said. "Even if you know that the conditions might be right for a wildfire, you can wake up and the fire's in your front yard."

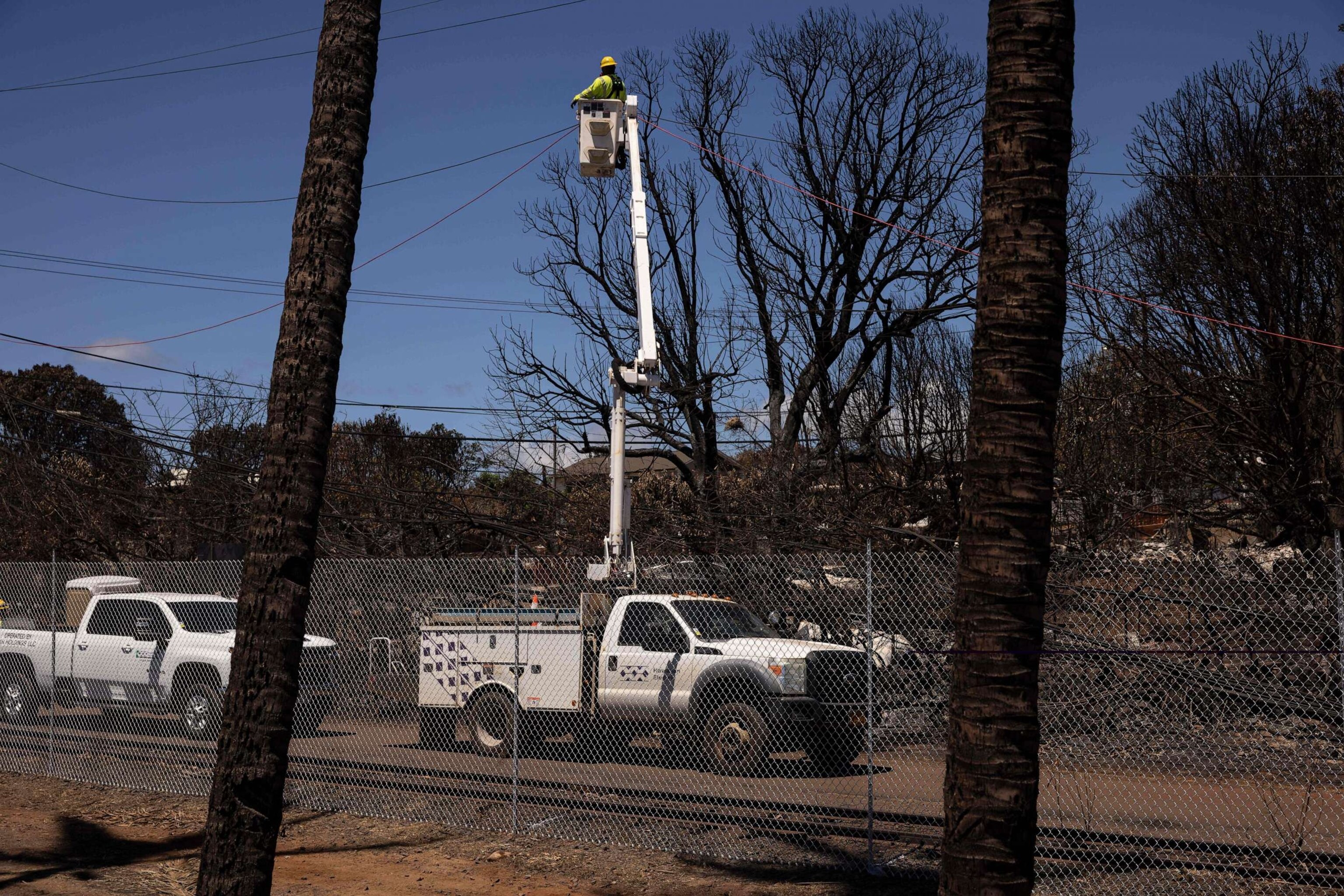

Power not shut off

Just after midnight on Aug. 8, amid high wind conditions, a brush fire was reported in the Kula area in the central part of Maui, according to officials. That fire may have been caused by damaged power lines, according to research conducted by a power monitoring company.

Several hours later, around 6:30 a.m., a brush fire was reported in Lahaina in the area of Lahainaluna Road. A resident livestreamed a downed power line on the road at 6:40 a.m., as brush can be seen burning and smoking. The fire would be declared 100% contained just before 9 a.m., before flaring up again and causing the life-or-death situation in Lahaina that afternoon.

A class action lawsuit by Lahaina victims and survivors alleges Hawaiian Electric "inexcusably kept their power lines energized" despite forecasts of high winds that could topple power lines and potentially ignite a fast-spreading blaze.

In a statement to ABC News, Hawaiian Electric said, "At this early stage, the cause of the fire has not been determined and we will work with the state and county as they conduct their review."

Yana Valachovic, the county director-forest advisor for the University of California Cooperative Extension in Humboldt and Del Norte counties, told ABC News it's "easy to armchair quarterback" the response, though much remains unclear.

"Reporting seems to suggest that, did people not pay attention to how much the winds were going to be a factor? Why weren't the power lines de-energized? And why wasn't an evacuation triggered from that early morning ignition when they thought they got it? And I don't know," she said. "I don't know what went into those decisions at that point."

Valachovic noted that in California, utilities may temporarily turn off power to reduce the risk of fires caused by electric infrastructure. Utilities may cut power to electrical lines as a last resort if they believe there is an "imminent and significant risk that strong winds may topple power lines or cause major vegetation-related issues leading to increased risk of wildfires," according to the California Public Utilities Commission.

Valachovic said the last resort of shutting off power is a complicated decision, and it's unclear what the threshold was in Maui to trigger that.

"The downstream effect of people without power, the economic losses of being without power, are not trivial," she said. "Certainly, it would have made a difference in this case, to shut the power off. But what were the signals going into it? And once you pull that trigger, it's a big deal."

Sirens not turned on

Sirens are scattered along much of Maui's coast, designed to alert people in the event of a hazard like a natural disaster. As the fires raged, they weren't activated.

Officials have come under scrutiny for not using the sirens, especially as some survivors who fled the flames reported not having any cell service or power amid widespread outages to receive alerts that were sent out.

Now-former Maui Emergency Management Agency Administrator Herman Andaya said the protocol is to use the coastal sirens only during tsunami warnings, not during wildfires, and that they feared people would head inland, toward the fire, if they sounded them. Andaya has since resigned, citing health reasons.

Valachovic said how people would have interpreted the alarm in Maui is important.

"Would it have been interpreted as something that would have said, go to higher ground, which is the wrong direction," she said.

DeYoung said it's difficult for her to assess the alert response in Maui at this time because "things are so context-specific when it comes to hazards," though surmised the capabilities of the siren system will likely be part of the investigation into the fire.

Broadly speaking, officials need to consider the limitations of the technology they're using to deliver alerts and have multiple ways of delivering them to as many people as possible, especially those who are hearing- or vision-impaired or do not speak English as a first language, DeYoung said.

"I absolutely think we should look at the overall adequacy of warning systems, and we should always be thinking about how we can improve warning systems," DeYoung said.

In deadly fires, a lack of communication often plays a part, Dicus said.

"[Maui] breaks my heart to the core because I've seen this play out in California, Canada, Australia, Mediterranean Europe -- it's almost the same story played out over and over and over again," he said. "One commonality obviously is just the lack of communication to the residents and the people living in the fire's path."

Valachovic said redundancy is key when alerting people during natural disasters, such as through sirens, text messages and first responders banging on doors.

"The system has to work, and not have a failure point in it," she said. "Some people have some forms of technology. Some people can hear, some people are near the sirens, some people are somewhere else. You have to have a system to reach everybody wherever they're at."

Understanding the death toll

As crews continue to search the destroyed area in Lahaina for potential victims, looking at who the victims were will help understand why the fire was so deadly, according to DeYoung.

For instance, in 2018's Camp Fire, the deadliest wildfire in California's history, many of the victims had mobility issues and were older and/or disabled, she said.

Looking at where they were found will also be crucial, she said, such as whether they were in their cars, on foot or in their homes.

Knowing the actions and locations of the survivors, and what the paths of exit were, will also be key, she said.

So far, only a fraction of the more than 110 victims found in Maui have been identified. The first 80 victims were found on Front Street in cars and along the water, according to the governor.

"It will be important to understand the kinds of people that were killed and where they were located," DeYoung said. "Or was it more related to people of all ages, but it was because they were stuck in that certain line of traffic? I don't know the answer to that yet."