Meet the 29-year-old computer scientist who wrote the algorithm for the first black hole picture

She's a Michigan and MIT grad.

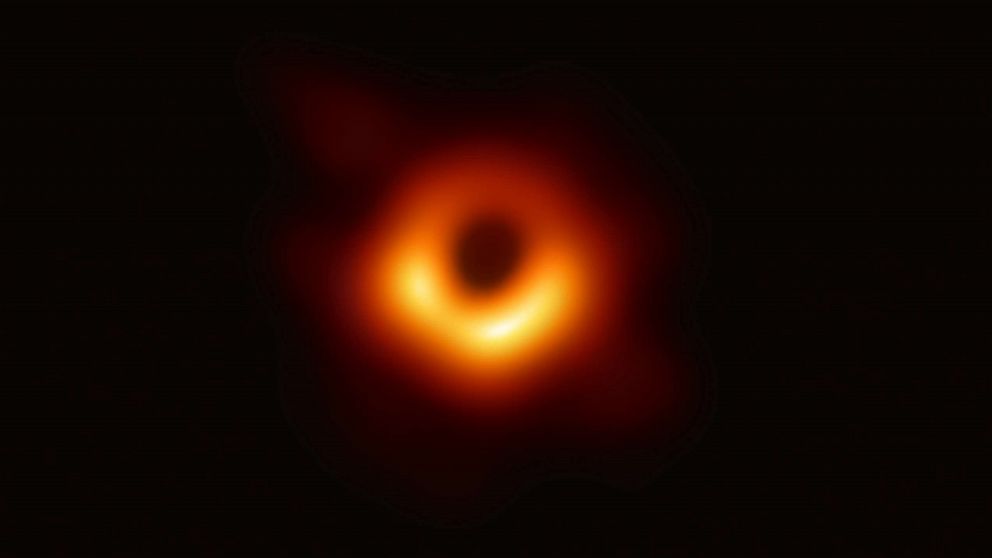

After an international group of scientists revealed the first photos of a black hole on Wednesday, the internet quickly turned its attention to the 29-year-old computer scientist who played a key role.

Katherine "Katie" Bouman, a postdoctoral fellow with the Event Horizon Telescope, created the algorithm that stitched together data from the global network of satellites that produced the historic image.

The EHT project used radio dishes scattered around the world to create a large, Earth-sized telescope. Bouman's specialty is using "emerging computational methods to push the boundaries of interdisciplinary imaging," according to the bio on her website.

That's pretty much what she did in creating the algorithm behind the black hole close-up.

Bouman's contribution eventually got the attention of freshman Congressman Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who tweeted, "Take your rightful seat in history, Dr. Bouman! Congratulations and thank you for your enormous contribution to the advancements of science and mankind."

Black holes are areas so massive they warp space and time so much that even light cannot escape. As such they aren't visible directly, but are surrounded by dust and gas swirling around it at velocities near the speed of light, which causes the detectable emission of radiation. The boundary of a black hole is called an event horizon.

"Bouman prepared a large database of synthetic astronomical images and the measurements they would yield at different telescopes, given random fluctuations in atmospheric noise, thermal noise from the telescopes themselves, and other types of noise. Her algorithm was frequently better than its predecessors at reconstructing the original image from the measurements and tended to handle noise better," according to a press release from 2016 from MIT, where she developed the algorithm.

“Radio wavelengths come with a lot of advantages,” Bouman said in the press release. “Just like how radio frequencies will go through walls, they pierce through galactic dust. We would never be able to see into the center of our galaxy in visible wavelengths because there’s too much stuff in between.”

The attention on Bouman may give a skewed impression of the number of women involved in the EHT project.

Feryal Ozel, an astrophysicist at the University of Arizona who was the modeling and analysis lead on the project, told ABC News the gender breakdown was "pretty dismal," noting that there were about three senior women, including herself, out of about 200 total scientists on the project.

"I've been a lot of projects where it's better. We are trying to change that," she said. "We are trying to bring in graduate students and postdocs and a younger generation that is excited to work on this. Hopefully that's changing the face of the collaboration a little bit. But we still have work to do."

Bouman did not immediately respond to ABC News' request for an interview.