Minority communities’ distrust of COVID-19 vaccine poses challenge

“We have to take part in the process," said trial participant Anthony Williams.

Before Anthony Williams received his first shot of an experimental COVID-19 vaccine in October, friends and family questioned why he’d trust a health care system that had historically brutalized Black people -- and with a drug so new, at that.

“You’re gonna let them test this on you? You’re gonna be a guinea pig for these people? I won’t believe it until I see them do it,” Williams, Ph.D., said people told him. “Things that just, conceptually, don’t make sense from the science end but that culturally and colloquially make perfect sense. There is a longstanding, centuries-long history of brutality against people of color, from the Tuskegee syphilis experiments to Henrietta Lacks.”

Lacks was a young Black mother of five who sought cervical cancer treatment in 1951, and, in the process, unknowingly had cells taken from her tumor. These cells, known as HeLa cells, were incredibly durable and have led to medical breakthroughs over the years. However, her case raised serious ethical issues with regard to biomedical research, including the role of informed consent and medical privacy, for which federal laws now exist today.

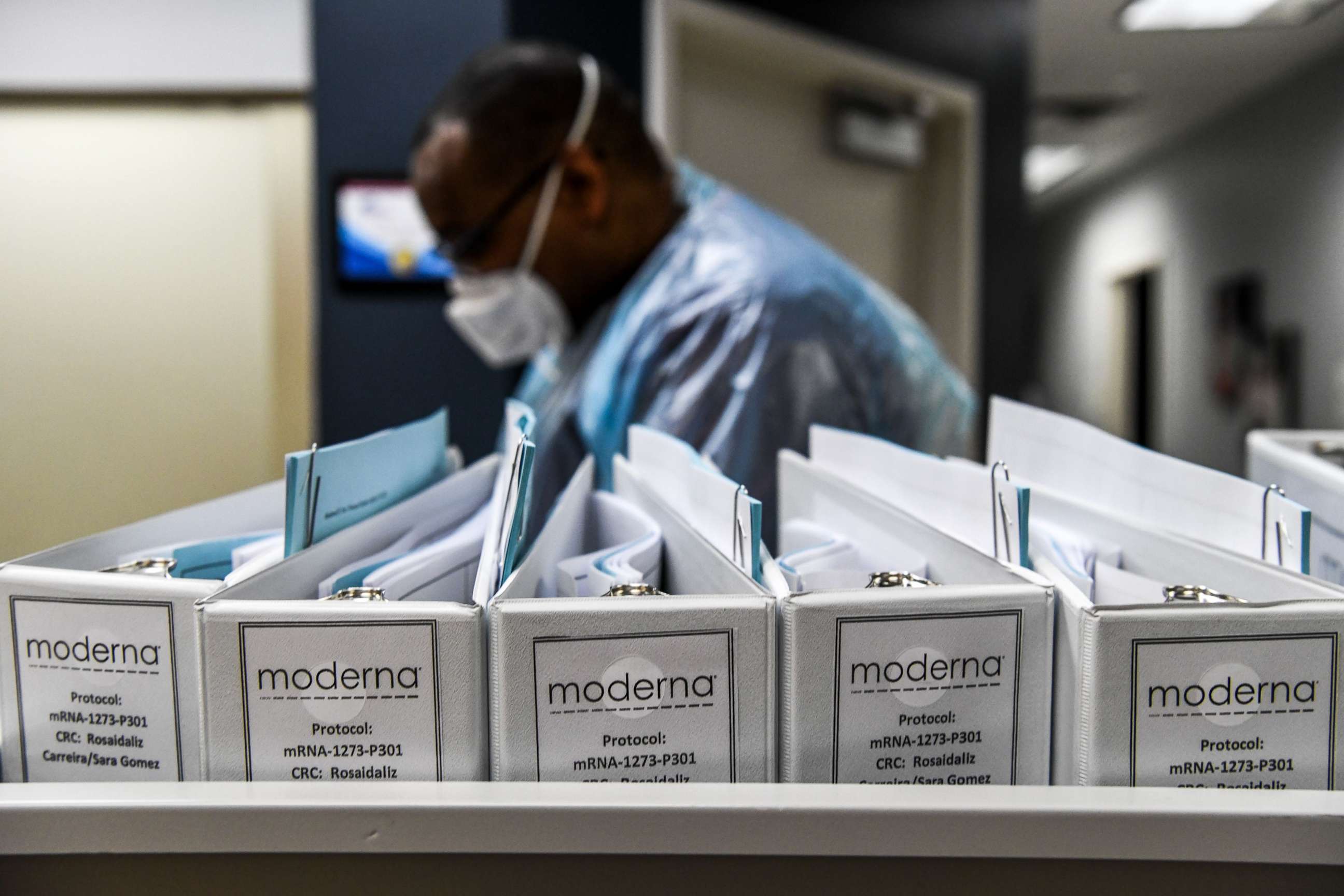

Williams said he was once skeptical of the medical system, too. Even participating in Moderna’s clinical trial was “not a light decision.” But he said it’s also time to break this cycle of distrust to assist in narrowing health disparities affecting Black people and other minority groups.

“For us to traverse these disparities, we have to contribute,” he said. “We have to take part in the process.”

Williams calls himself “a bit of an outlier.” Having grown up “in a bad neighborhood” in Chicago's South Side, he’s now a cancer biologist at the University of Chicago, where he says his life experiences drive his passion for his work.

His experiences have also given him a perspective on both sides. Without concerted efforts from the health care community and people of color to make amends and build trust, he said it’ll be difficult to get the COVID-19 vaccine to minority communities, which have been impacted disproportionately by the coronavirus pandemic.

“It’s a lack of commitment from the health care community to say, ‘Hey, we have dogged these people… We have to make a concerted campaign and effort to start breaking this cycle,’ and then on the flip-side, from the community, saying, ‘Hey, we need to be in a position to take charge of our wellness and health care.'"

"I would love to see the olive branch extended from the medical community first," he added.

Who will get the vaccine first?

Both Moderna and Pfizer have applied for emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration for their vaccines, which have shown over 90% efficacy in phase 3 clinical trials. If both vaccines are approved, there could be 40 million doses of the vaccine distributed by the end of December, with an additional 5 to 10 million doses each week thereafter, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), which is composed of a variety of non-government experts.

The advisory committee voted Tuesday on an interim recommendation that health care personnel who are treating patients, including those working and living in nursing homes and other long-term care facilities, should receive the first doses of the vaccine once it’s approved as part of the first subgroup of the phase 1 rollout.

And though they haven’t voted on the other subgroups yet, the committee’s chair, Dr. José Romero, told ABC News that essential workers are expected to come next, followed by adults who are over 65 years old or who have high-risk medical conditions. Once their recommendations are finalized, it’ll be up to the states to individually determine further prioritization.

Romero said the ACIP has met frequently since April to “make sure that there is a fair, equitable and transparent distribution of these vaccines” given their limited quantity over the first few months that they’ll be available.

Within all of the aforementioned groups, Romero says minority populations are included.

“When we talk about, for example, health care providers, we’re not talking about just the doctors, nurses or respiratory therapists that are taking care of the patients in the hospital,” said Romero, who is also Arkansas’ secretary of health. “We've expanded that to include the essential individuals that helped make the institution run. So that would include, for example, the housecleaning staff that has to turn over the room very quickly to get the next patient in the emergency room ... the food delivery staff, the administration staff that are at the front desk of the emergency room.”

“We understand that underprivileged minority populations, lower-paid individuals are in that group,” he added. “And so, because of that, that expands the equitability of the recommendation.”

He said the essential worker group would include those who work in areas like meatpacking, poultry packing and agriculture, “where we know that there’s a significant portion of the minority population and low-wage earners in that group.”

Nevertheless, Romero also acknowledged that there will be hesitation among many minorities to take the vaccine, and he said there will have to be multi-pronged approaches to reaching the communities most skeptical.

Dispelling myths

Only 55% of Black Americans said they would take a vaccine if it was proven safe and effective by officials, compared to seven in 10 white and Hispanic adults, according to a November Axios/Ipsos poll. While optimism about the vaccine is growing, a Gallup poll found that the top two reasons people gave for choosing not to get vaccinated were “concerns about rushed timeline” and “wanting to wait to confirm it’s safe.”

In Miami, Dr. Olveen Carrasquillo is a principal investigator in Janssen’s phase 3 COVID-19 vaccine clinical trial, in which he said 60% of the trial participants have been from a minority group. He said all the misinformation surrounding the vaccine has been a huge concern.

Many patients, he said, have told him they “don’t want the Trump vaccine.”

“I think that has died down since the election ... but there are concerns this is very politically motivated,” Carrasquillo, who is also the chief of general internal medicine at the University of Miami's Miller School of Medicine, told ABC News.

But the conspiracy theories surrounding the COVID-19 vaccine have become more outrageous than those regarding the flu shot, he said. Every year, he said they struggle to convince people to take the flu shot, because the patients believe the shot will actually make them sick with the flu. “That’s not correct,” Carrasquillo said.

“I guess the word is frustrating, but, I mean, I’m very embarrassed and ashamed for many people, particularly our political leaders -- the kind of crazy stuff that some of them are spreading, it’s amazing, and that number of people that really espouse stuff that has no basis in science or fact,” he said. “It concerns me for the future of our nation.”

“To overcome this pandemic, you need clear communication,” he added. “You need to be concise, and you need to be 100% factual.”

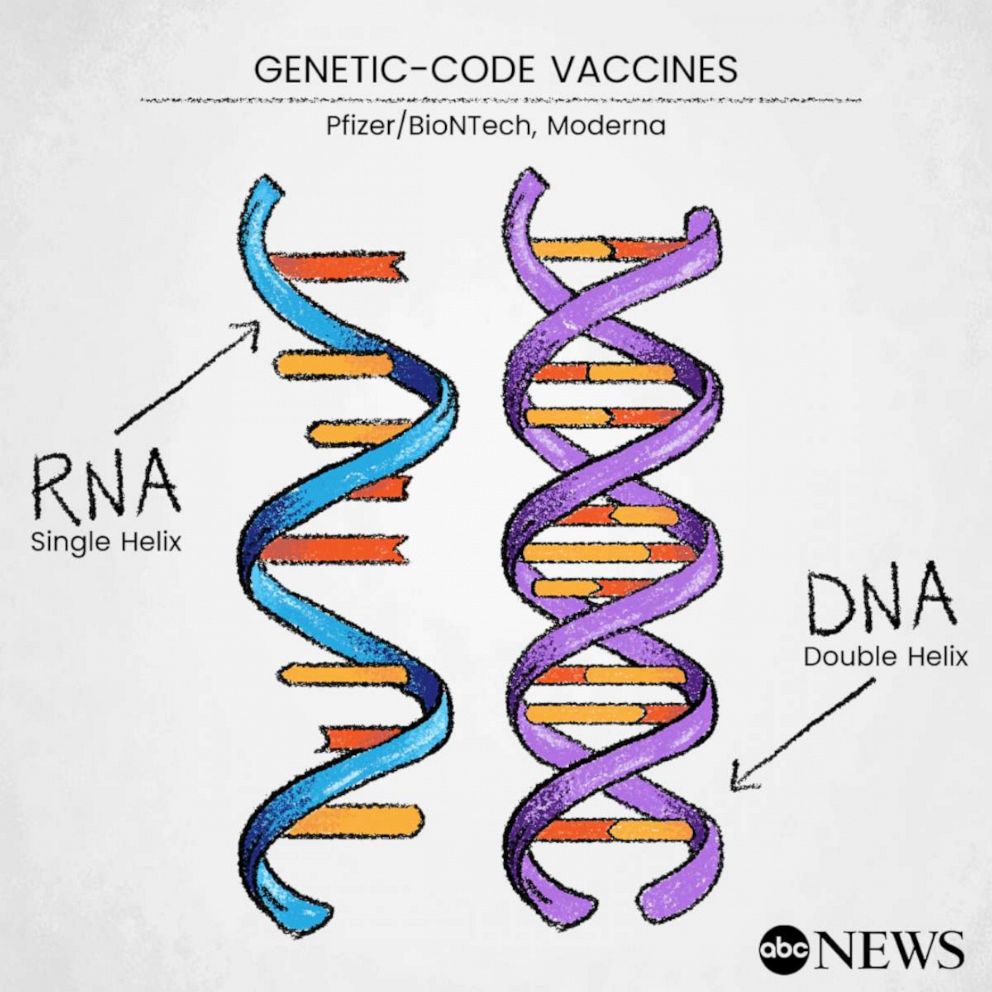

Both Moderna and Pfizer’s vaccines are different from the more traditional ones that rely on a weakened or dead version of a virus to trigger the body to build an immune response. Instead, they use genetic codes -- mRNA -- to provide the immune system with instructions on how to recognize and attack the proteins found on the COVID-19 virus.

The technology has never been used outside of the lab, but it has been in development for years and was originally planned for rollout in 2023, according to Pfizer's partner in COVID-19 development, BioNTech CEO Dr. Ugur Sahin. The pandemic accelerated those plans, he said.

Neither Moderna nor Pfizer reported any serious adverse side effects from their vaccines following their phase 3 trials. Common side effects were mild, including fatigue, headache and fever, all of which are similar to the side effects caused by other vaccines, according to Dr. Richard Novak, a lead investigator of the Moderna clinical trial in Chicago.

“Those reactions are really just the immune system reacting to a vaccine product, and that’s actually what we call an inflammatory response, which you might see when you get any type of immune reaction,” Novak, who also heads the Division of Infectious Diseases at UI Health, told ABC News.

Novak said these mild side effects are “a sign” the vaccine is working and can easily be treated with an over-the-counter medication like Tylenol.

Novak said people should consider the alternative to not getting vaccinated.

“What I would say to people is getting COVID-19 is not safe,” he said. “Here, we have really good safety data and the vaccines are really effective at preventing you from getting sick. ... The risks of doing poorly with coronavirus are much higher than what most have been shown from the vaccine.”

Romero, the ACIP chair, said the pharmaceutical companies -- regardless of the kind of vaccine they’re making -- and the FDA have been committed to ensuring safety despite the accelerated process. He said the official reviews for these vaccines would be “nonetheless rigorous as it has been for other vaccines.”

With only preliminary data from their phase 3 trials, both Moderna and Pfizer have promised to publish the full details of their studies through a formal scientific peer-reviewed process. Other pharmaceutical companies currently working on COVID-19 vaccines have promised the same.

Once the vaccines have begun distribution, there will also be a variety of safety monitoring systems, including the national Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System and a new smartphone-based V-SAFE app, which will use text messages and surveys to check on recipients’ health. Romero said these will help build safety data based on millions of people rather than the hundreds of thousands involved in the studies, and the information will allow vaccine makers to tweak future iterations.

Ultimately, Carrasquillo said that if all the vaccines achieve the minimum threshold for efficacy, which the FDA set at 50%, then that’ll be “much better than where we are now.”

“[I’m] hoping we’ll have enough vaccine[s] to vaccinate the world,” he said. “Eventually we can worry about, ‘Oh, this one’s a little better than this one.’ ... We’ll sort everything out over the long term... But at least we know the vaccines work in the short term.”

Reaching the community

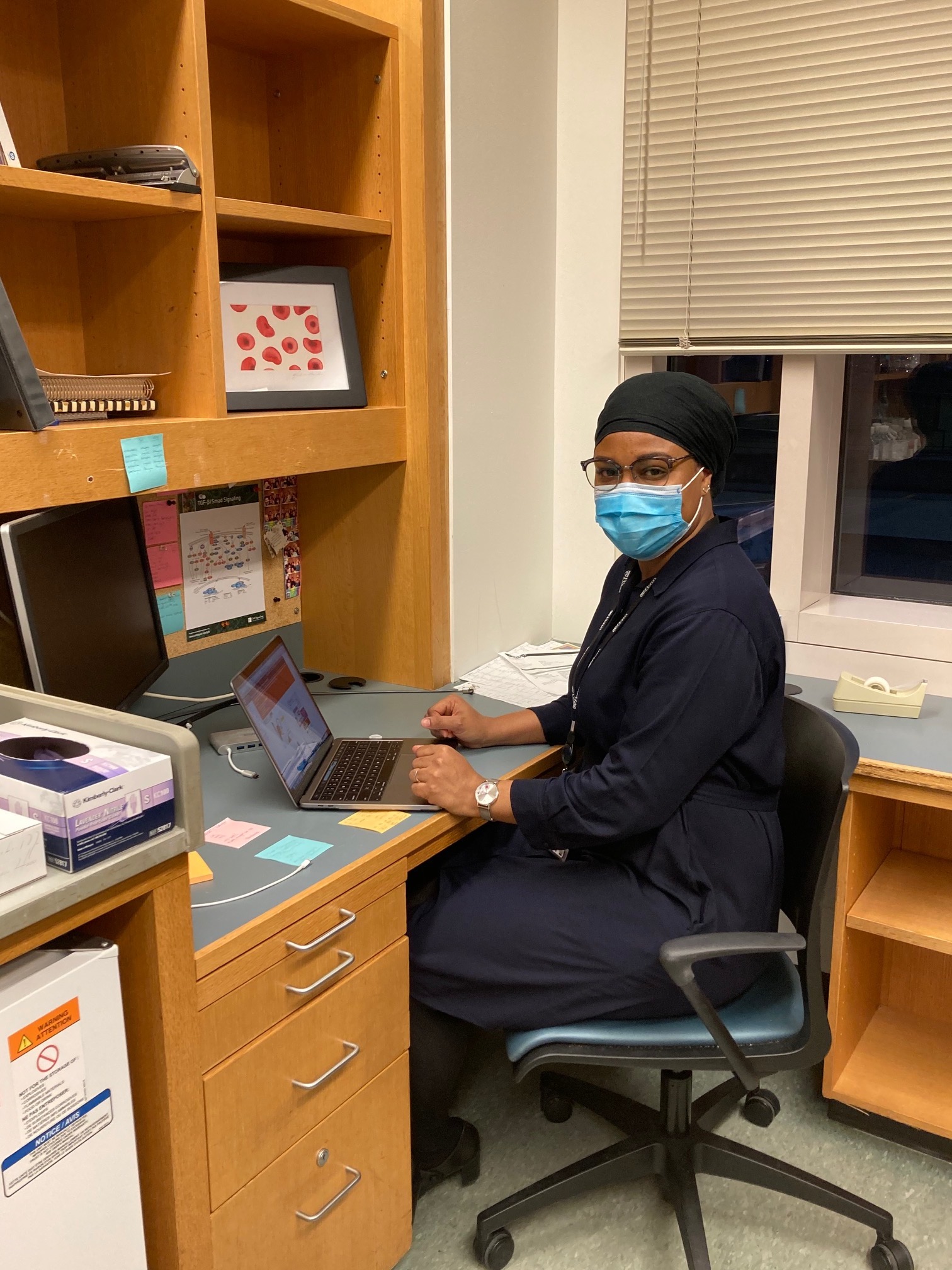

Suean Fontenard, Ph.D., is another participant in Moderna’s clinical trial who said she participated in the study not only to “contribute to science” as a biomedical researcher at the University of Pennsylvania but also because she wanted to help her community.

“COVID is hurting our community at disproportionate levels... I’m not a virologist, I don’t work in a vaccine lab. I can’t help in that way,” she said. “But I could put myself out there and help push the science forward, and we got good results… So that’s telling me that I’m doing something that is useful and that will help people for sure.”

Fontenard said she’s now on a mission to educate and encourage other people to get the vaccine if it’s proven to work and can save lives.

“COVID doesn’t play. We hear about the percentages of people that die like that’s something we should be able to live with,” she said.

In part, word of mouth -- such as that through Fontenard and Williams, the Chicago cancer biologist -- will be one way in which communities of color can gain trust for the COVID-19 vaccine, according to Dr. Katya Corado, an investigator in the Oxford University-AstraZeneca vaccine trial at the Lundquist Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in Torrance, California.

Corado said pre-existing bonds between people’s primary care physicians will also help, along with minority representation throughout the study leadership and outreach in places where people tend to congregate, such as community health centers, churches and barbershops.

Carrasquillo and Novak also said there are outreach efforts being developed in Chicago and Miami to disseminate vaccine information to minority groups. Novak, who is working on the Moderna vaccine, said they're developing two programs that’ll enlist high school and college students as ambassadors to reach out to their communities.

“There’s a tremendous amount of interest from young people who want to help,” he said.

The FDA is scheduled to review Pfizer’s request for emergency use authorization for its COVID-19 vaccine in a public hearing on Dec. 10. It’ll hold a hearing for Moderna’s vaccine a week later on Dec. 17. The ACIP is expected to release final recommendations specific to each vaccine following these reviews.

“A final recommendation isn’t going to be issued until we see that safety and efficacy data,” Romero said. “So all that goes to show that safety is first and foremost in licensing these vaccines. Once they're licensed, there is safety monitoring that continues after the fact.”

Carrasquillo said the world is in a better place than it was four months ago, when he felt like he couldn’t offer hope to those he spoke to. Now, he said he can tell people, “We’re going to get over this.”

“By the end of next year, we’re going to be in a much better position than we are right now, and so, people got to know hope,” he said. “I mean, I think that’s critically important. This has really stressed people; it’s caused a lot of mental health issues. ... And I keep telling people, now I see the light at the end of the tunnel, and I think that’s very important for people to know.”

This report was featured in the Thursday, Dec. 10, 2020, episode of “Start Here,” ABC News’ daily news podcast.

"Start Here" offers a straightforward look at the day's top stories in 20 minutes. Listen for free every weekday on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, the ABC News app or wherever you get your podcasts.