How the racially-motivated cold case murder of young Black man was finally solved decades later

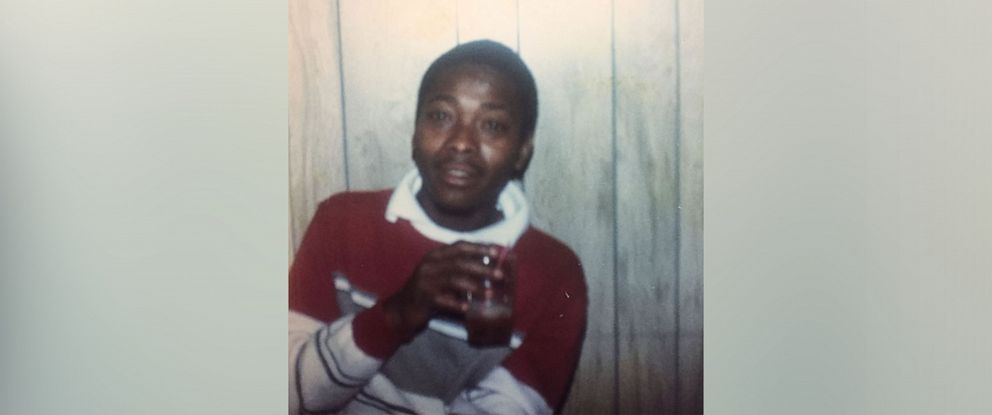

Georgia native Timothy Coggins was found brutally murdered in Oct. 1983

To Jesse Gates, that October night in 1983 seemed like any other in Griffin, Georgia.

The former Spalding County sheriff’s deputy was out driving when he came upon his good friend Timothy Coggins walking down the street.

Recognizing his vehicle, Coggins waved him down. They had been friends for a long time, Gates said, so he pulled over and Coggins asked him for a ride to a dance club outside of town called People’s Choice.

During the roughly 15-minute drive over, Gates, who was one of the county’s few Black officers at the time, said Coggins, also a Black man, mentioned he was dating a white woman.

“I said, ‘Man, you need to watch yourself on dating them sisters like that because we live in Griffin, Georgia, and not Atlanta, and some people just don’t accept things like that,” Gates said.

As Gates pulled up to the club, he said he noticed three white men hanging around outside. He thought that was “strange,” he said, because “white guys did not come to that club” and he felt uneasy about the whole scene.

But Coggins got out of the car and headed in. Gates never saw him again.

“I had no way of knowing that I had dropped that boy off to his death,” he said.

Coggins was found brutally murdered near a power line in an open area in Sunnyside, Georgia -- a few miles outside of Griffin -- on Oct. 9, 1983. The area is marked by an oak tree that was a well-known gathering place for drug deals and parties.

He had suffered multiple stab wounds and was tortured — his body chained to the back of a vehicle and dragged before it was dumped by a wood pile, according to the Spalding County Sheriff’s Office.

Former Spalding County sheriff’s deputy Oscar Jordan, another one of the few Black officers on the force at the time, said he was called into the coroner’s office and asked to identify the body.

“He had seven stab wounds to the front of his chest. … And then he had a cross cut across the chest. And then, [on his] back, it was the same way. I was later told that it represented the Confederate flag,” Jordan said. “When I reported back to the sheriff ... I told him I did not know who this individual was. There was no way that I could know, because he was so disfigured.”

“The worst part about it [is] they didn't kill him,” he added. “[The] autopsy showed he bled out. Thrown behind a pile of wood. Left to die.”

Coggins was just 23 years old.

The Coggins story is now the subject of a new program called “In The Cold Dark Night” from ABC News “20/20” and Lone Wolf Studios that will air on Friday, July 17 at 9 p.m. ET on ABC.

The program features extensive reporting and interviews conducted by Stephen Robert Morse, director, producer and writer, and Max Peltz, producer and writer, of “In The Cold Dark Night” for Lone Wolf Studios in association with Radical Media. Miikka Leskinen is editor, co-producer and writer of the program.

After his body was found, sheriff’s deputies went door to door in Griffin, trying to identify Coggins. Eventually, they knocked on his sister’s door.

Coggins’ brother, Tyrone Coggins, said his death took a heavy toll on the family.

“We were shocked. We’re like, ‘Who would hurt this guy?’” he said. “You know, this was Tim. This was the smooth guy. The guy that never bothered nobody. Always helped somebody.”

His sister, Telisa Coggins, remembers her brother Tim as someone who was very sweet and outgoing. He was the kind of person “who could get along with anybody,” she said.

In fact, she had been at the People’s Choice club with him the night he disappeared. She said she remembered a white woman started going to the club and she thought her brother was teaching the woman how to dance that night. She said she also remembered a white man looking for her brother and that same white man walking out of the club with him as she went to the restroom.

“By the time I got out the door, they was gone,” she said.

The sheriff’s office and the Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI) gathered evidence and conducted multiple interviews in the Coggins case, but weeks turned into months and no arrests were made.

Gates, who was an active sheriff’s deputy in the '80s, said he believes Coggins’ death was centered around the white woman and money. Notes from the officers who had been working the case at the time indicated their theory was Coggins had taken money as part of a drug deal. Coggins was known for making small drug deals around town, authorities said.

Jordan, who was also an active sheriff’s deputy in the '80s, said, “We never learned where the money went to, but I can recall being told that Tim was absolutely terrified, and he was desperately trying to get up that money.”

Gates and Jordan worked the case for weeks until they started getting close to finding a suspect and were taken off, Gates said. He said he believes it was someone who lived in the trailer park near the area where Coggins was found.

“You had a lot of vicious people in that trailer park, and I knew somebody in that trailer park called that sheriff,” Gates said.

Jordan said he was told the investigation had reached a “dead end,” whereas Gates said he was told “it wasn’t my job [to investigate this case] because I was a road deputy, and I wasn’t a so-called investigator.”

“I don’t think the attention that should have been put on this case was put on this case,” Jordan said. “Probably due to, you know, the color [of his skin].”

Months gave way to years, and then decades, without any arrests.

The case sat dormant for 33 years.

Then, in 2016, the Coggins case was re-examined and new investigative leads began to emerge. GBI special agent Jared Coleman, who was assigned to re-examine the Tim Coggins’ case, said he alerted the then newly-elected Spalding County sheriff Darrell Dix when he thought he had a new lead.

Dix didn’t hesitate to take a fresh look.

“My motivation to solve this case without a doubt is the fact that it's the right thing to do,” Dix said. “I believe that there's a lot of honor involved in doing it, and I want to give closure to the Coggins family. I wanna let Timothy Coggins rest in peace. And by doing that, that's doing the right thing.”

Dix said that in the years since the murder, some of the evidence that had been collected had gone missing. But he said officials found something that gave them insight into the Spalding County Sheriff’s Department and the local police department at the time Tim Coggins was killed.

“We were looking everywhere that we could, and we went to where there are some old property archived downtown,” Dix said. “And while we were looking for stuff dealing with the case, we came up with this small black notebook.”

The notebook turned out to be the diary a former sheriff’s deputy kept in the 1980s. His writings detailed how he had infiltrated the local Ku Klux Klan to gather information and learned the KKK might have infiltrated the police departments. One entry, dated Thursday, May 20, 1982, said that one of the local KKK leaders boasted about having “a number of good Klan in the police and sheriff's departments."

"At this point unsure of who to trust. Will try and find out who in the department is Klan," the entry continued.

Dix said it spoke to the climate in the area at the time. The diary had been written about a year before Coggins’ body was found, he said.

“Racist white men basically controlled the city, ran the businesses and you had these elected officials that were racist white men that pretty much controlled everything,” said Cynthia Ward, a city commissioner who is also Coggins’ cousin. “A young Black man being killed-- that was not important to them and they didn’t care about bringing the media in to see what happened because it was just another Black person dead.”

In re-examining the case, GBI special agent Coleman found that a convicted child molester felon named Christopher Vaughn, had come forward to the GBI in 2007, saying he had information on who killed Coggins.

Coleman said Vaughn had been interviewed by law enforcement a few times in the past but that nothing was done with the information.

After interviewing Vaughn on April 26, 2017, Coleman turned his attention to Frank Gebhardt and William "Bill" Moore Sr., two local men local authorities said were known to have “intimidating” reputations.

“Mr. Moore and Mr. Gebhardt both have an extensive criminal history and Mr. Gebhardt had been interviewed back in 1983, but no real further investigative acts pursued in the investigation,” Coleman said. “Christopher Vaughn lived at a house that was right at the corner of Carey’s Mobile Home Park, which is the last known location that Timothy Coggins was seen alive.”

Vaughn told Coleman that Gebhardt had told him Coggins was having sex with his girlfriend at the time, Ruth Elizabeth Guy, also known as "Mickey," and that’s why Gebhardt and Moore killed him. Coleman said they believe the white woman Coggins danced with at the club the night he was last seen was the same woman, Ruth.

“That was the tipping point for the murder,” said Coleman. “We do know that a week or two weeks after the murder occurred, that Mickey Guy left the state of Georgia. But she died in 2010.”

Dix suggested people who knew Gebhardt and Moore back then were scared to come forward for fear of repercussions.

“So when things like this happened, people were scared to talk about what had happened,” Dix said. “They were scared to talk about what they knew because they were in fear of retribution. They were afraid that these people were gonna come kill them or kill somebody in their families, because that’s the type of reputations these people had.”

Gebhardt was interviewed by Coleman in 2017. At the time, Gebhardt was incarcerated on unrelated charges, and during his interview, he denied ever hearing about Coggins’ murder or even knowing the victim.

Gebhardt’s sister, Sandra Bunn, said both her brother and Moore denied having anything to do with the Coggins murder.

“He [Gebhardt] told me, ‘I don’t have nothing to talk about, and I know nothing,’” Bunn said. ‘Both of them says they know nothing.”

But Dix said they decided to monitor Gebhardt’s prison phone calls with Bunn -- she was the one he called the most.

During one of these calls, Bunn was heard telling her brother, “Keep your mouth shut. Y’all agree to no [DNA] tests. Y’all agree to nothing.” She advised her brother to avoid giving the investigators his DNA through means such as accepting drinks, which would transfer his saliva.

In the end, Dix obtained a court order to get a DNA sample from Gebhardt.

“I have never had this much trouble out of one sheriff in my life, and I’ve been living here all my life,” said Bunn. “Never had I had this much trouble. Darrell Dix is playing the media to do this -- to make him look good, to get the Black votes -- and they just hearing Darrell Dix’s side. They hearing nothing else.”

In an unusual move, Dix said the sheriff’s department told the media in 2017 that they were close to making an arrest in the Coggins case even though they still needed more evidence. Their hope was that it would encourage more people to come forward with information that could lead to an arrest.

Their “gamble,” as Dix called it, paid off.

One of those people was Shirley Sisk, who managed the trailer park where Moore had lived. In an interview with investigators, Sisk said one night in the ‘80s, she was talking with Brenda Moore, his wife and Gebhardt’s sister, who she said sounded drunk. According to Sisk, Brenda Moore told her that her husband and brother were planning to kill a man.

“She said, ‘I’m telling you, he’s gonna kill him. They’re gonna tie him up and they’re gonna drag him with a car or truck,’” Sisk said during an interview with investigators. “And I’m going, ‘Brenda, get your drunk ‘A’ over there and go to bed.’ You know, a drunk person, you just don’t know.

You really brush them off when you’ve got so many tenants, you really do,” she continued. “And you don’t wanna believe none of that but it was something about a boy. Well, it's several times, probably. I'm thinking several times, because Frankie was always gonna beat up somebody.”

Willard Sanders, Gebhardt’s neighbor, also came forward to tell authorities that Gebhardt had told him shortly after the murder that he had chained Coggins to the truck, but it was Moore who’d killed him. Sanders said he reported Gebhardt to the authorities at the time.

Gebhardt, then 59, and Moore, then 58, were charged in October 2017 with murder, felony murder, aggravated assault, aggravated battery and concealing the death of another in the Coggins case.

When it came to preparing for the trial, prosecutor Marie G. Broder said there were challenges. She said there was neither physical evidence nor DNA that pointed to Gebhardt and Moore having committed the crime. Plus, much of the evidence had disappeared years earlier.

“I have clothing from the scene from our victim and I have a sheet used to cover the victim and I have a rock, and that’s it,” she said.

Many of the witnesses were also convicted felons, she said, suggesting it would make a jury doubt their testimony. During their interviews, though, she said many of them had pushed her to search a well on Gebhardt’s property.

“He told too many people that he threw stuff in that well,” she said.

Broder was there watching when law enforcement performed an extraction on Gebhardt’s well. Sifting through items from the well, among the pieces of trash, authorities found a knife broken into multiple pieces, a sneaker and a shirt that appeared to show stabbing marks.

“When we spread the shirt out, I was excited but also sad, because in the back of that shirt were what appeared to be seven stab wounds, and according to the autopsy report, Timothy Coggins was stabbed in the back seven times,” Broder said.

Broder said she believes Gebhardt and Moore targeted Coggins because he was dealing marijuana in white neighborhoods as well as dating white women, and they wanted to send a message to other Black people.

“Timothy Coggins was a young Black man in 1983 who refused to follow societal norms. He was not following the rules of 1983, if you will,” Broder said. “And if you were a Klan member or a racist, any of those things would infuriate you and anger you to the point where Timothy Coggins became a target … that needed to be eliminated, and a message that needed to be sent.”

The Coggins family was subjected to threats following the murder. Former sheriff’s deputy Jordan said Tim Coggins’ stepfather received a call in which someone threatened more family members would die if the investigation into the killing continued. Telisa Coggins said one night someone threw a brick through their window with a message on it saying, “You’re next.”

“There has always been a racial divide in this community,” Dix said. “I’ve seen huge swings of the pendulum with the ill will between the Black and white community. Then I’ve also seen a lot of the Black and white community coming together for the good. And from my perspective, again, dealing with Mr. Coggins, we go out and do the right thing by arresting these people, Bill Moore and Frankie Gebhardt, because they thought they were untouchable. And I wanted to send a message, you’re not above the law and you are touchable.”

Gebhardt and Moore went to trial in the summer of 2018.

During the trial, Gebhardt’s defense attorney Larkin Lee said his strategy was to “attack everything, because there seemed to be no smoking gun.”

“It was basically jailhouse witnesses, or people that had a vendetta against Frankie Gebhardt, and scant evidence that was eventually recovered from the well that we thought amounted to nothing,” said Lee.

“They had a piece of a very tiny, appearing to be, old steak knife that was in Frankie Gebhardt’s trash sometime during the 1980s,” he added. “Sneakers that don’t match anything. A chain that they’re implying must have been used to drag Mr. Coggins’ body, but then they don’t match that up with the pulley and the bucket that were found, also in a well, which would make just total sense to find in a well. My opinion and our defense was [that] what the state put up in all of their so-called evidence equaled zero.”

The racial climate of the area at the time of the murder became a focal point for the prosecution at trial.

“In my opinion, there was a good bit of racism,” former sheriff’s deputy Oscar Jordan testified. “There were a lot of times when you would get a sense of not being welcomed or not being wanted.”

Gebhardt was ultimately found guilty in June 2018 for malice murder, felony murder, aggravated battery, aggravated assault and concealing the death of another. He was sentenced to life in prison plus 30 years.

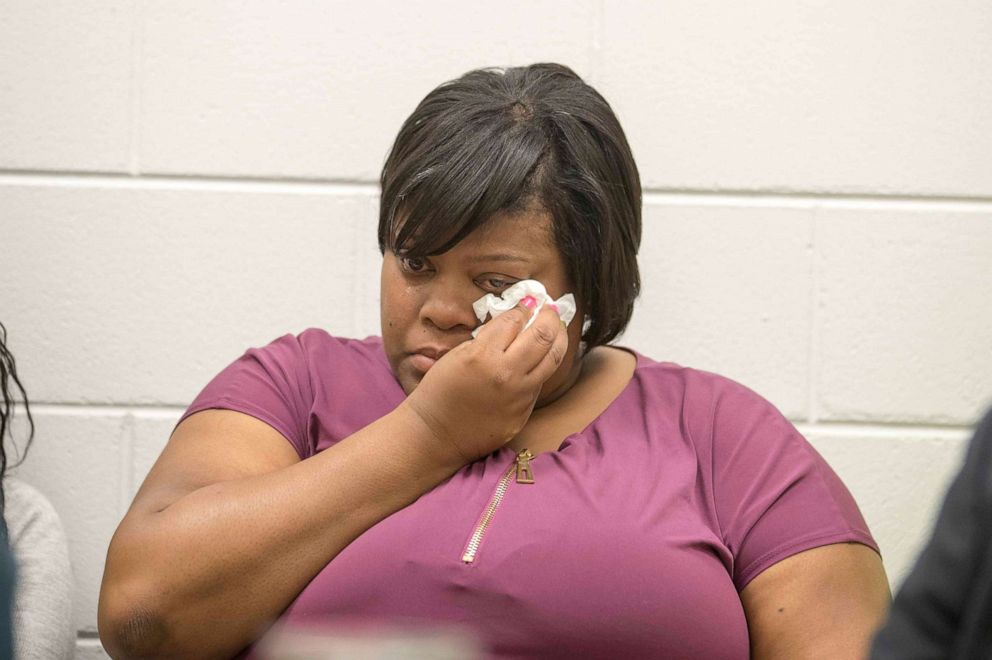

When the verdict was announced in court, Coggins’ family members quietly wept as they turned to hug each other.

“We never thought that this day would come,” Coggins’ brother Tyrone Coggins said. “We always hoped that it would come, we’ve just been so happy that my brother finally, finally got justice.”

“It has been 34 years for us to be here and we are finally here,” Coggins’ niece Heather Coggins added. “Now we can go back to Tim’s grave... and we can say, ‘hey, you guys can now rest in peace.’”

Ryan McMahon, the jury foreman, said prosecutors laid out a more compelling argument than the defense.

“I think the defense did the best they could with what they had,” he said. “They threw considerable doubt -- considerable doubt. But I think the prosecution had a much better story, and I think that there’s enough memory in this case that was backed up by physical evidence or by another person’s memory.”

He said the jury had counted 17 times in which Gebhardt had admitted to Coggins’ murder in one way or another over the years.

Gebhardt, who continues to maintain his innocence to this day, was denied a motion for a new trial by the Spalding County Superior Court.

His attorney said he felt his client had been used as “retribution for the racism of the past.”

“This was the least evidence against any defendant in any case I’ve ever been involved with,” Lee said. “I don’t believe that they actually found the answers that needed to be found. They may have gotten a conviction but I don’t think it resulted in actual justice as far as who has actually committed this offense.”

Moore, meanwhile, agreed to a plea deal. He pleaded guilty in August 2018 to voluntary manslaughter and concealing the death of another and was sentenced to 20 years in prison and 10 years probation.

“My client did the best he could have done in this situation not to die in prison,” said Harry Charles, Moore’s defense attorney. “But he wasn’t remorseful because he felt he didn’t do anything wrong.”

For a long time, the Coggins family said they were too scared to place a headstone on Tim’s grave for fear that others in the community would vandalize it. For years after Coggins’ death, his grave remained unmarked.

With the trial behind them and two men serving time behind bars for killing their beloved uncle, cousin and brother, the Coggins family felt they could finally put him to rest the way they always wanted.

In a small ceremony at graveside in Dec. 2017, family and friends released purple balloons in his honor. A prayer was said, and the group shared hugs and took photos.

His headstone reads, “In loving memory, Timothy Wayne Coggins, gone, but never forgotten.”