'Wilderness to Wasteland': America's Dystopian Landscapes

David Hanson's photos capture the environmental degradation of the wilderness.

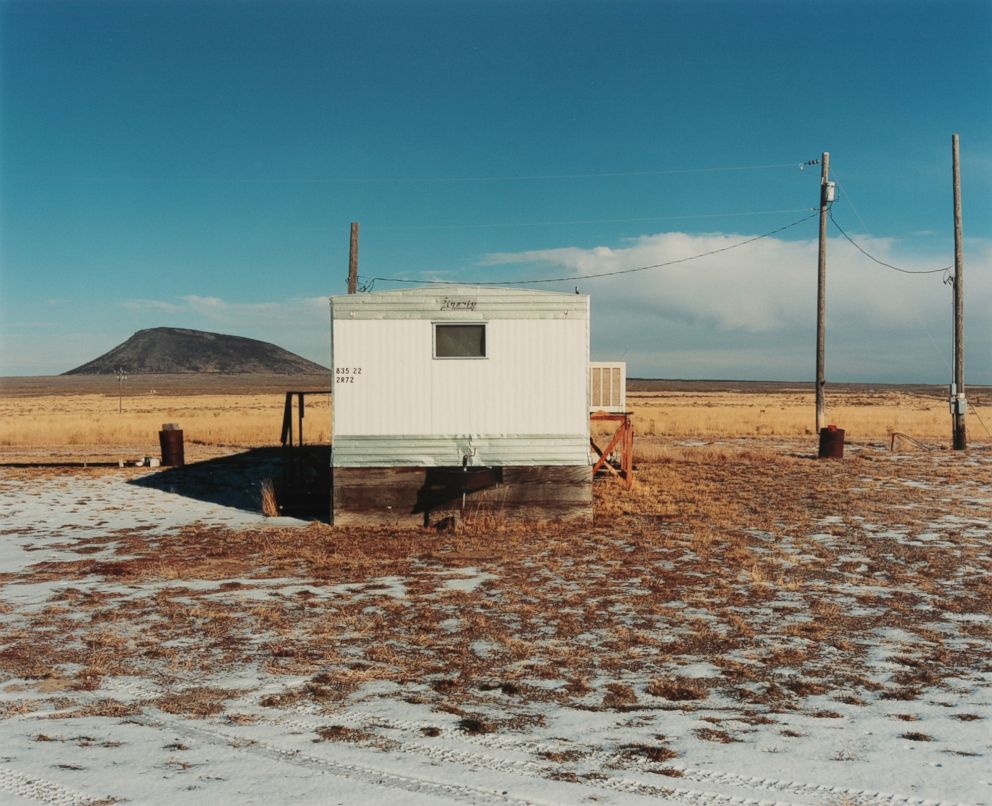

![Abandoned Union Carbide Lucky Mac uranium mine, Gas Hills, Fremont County, Wyoming, 1986 [Detail].](https://s.abcnews.com/images/US/HT_David_Hanson14_cf_160314_1_16x9_992.jpg?w=1600)

— -- David T. Hanson’s book “Wilderness to Wasteland” documents American landscapes forever altered by human industrial activity. As part of a Guggenheim Fellowship project, he visited 67 Superfund sites, which are among the thousands of locations the Environmental Protection Agency designates as the nation’s most contaminated.

The sites he chose included nineteenth-century mines, wood-processing plants, landfills, large petrochemical complexes and nuclear weapons plants. Hanson took the photos between 1982 and 1987, and he believes his photographs are still relevant today, given growing concerns about energy production, environmental degradation and climate change. His photographic survey of polluted waterways and swaths of land darkened by toxic waste reveals a geography of devastation.

Wilderness to Wasteland

The book is divided into four chapters: “Atomic City,” “The Richest Hill on Earth,” “Wilderness to Wasteland” and “Twilight in the Wilderness.” “Atomic City documents the site of the world’s first nuclear power plant; “The Richest Hill on Earth” concentrates on Butte, Montana, a mining town; “Wilderness to Wasteland” is a series of aerial and ground landscapes; and “Twilight in the Wilderness” shows night views of industrial sites.

Hanson first visited Atomic City, Idaho, in the fall of 1985 as he was driving from Montana to California to photograph hazardous waste sites throughout the United States. The research facility formerly known as the National Reactor Testing Station was nearby and was the site of a fatal nuclear reactor accident in 1961.“It was clearly an impoverished community,” Hanson said. “I was interested in this former nuclear boomtown-turned-ghost town as yet another example of the boom-to-bust cycles that have characterized the history of the American West.”

Hanson’s images show dilapidated mobile homes in a desolate landscape devoid of inhabitants. Snow covers the ground, and there is a palpable sense that a visitor could visit 30 or 100 years later and find the same scene, frozen in time.

“As I was creating all of these photographs, I saw them as monuments for the end of the twentieth century,” Hanson wrote in an email. “Displaying the dystopian side of progress, they form an extended investigation into nature and culture, the real and ideal, order and entropy. The photographs become, finally, meditations on a ravaged landscape.”

Hanson’s work calls to mind Edward Burtynsky’s photographs of oil fields, quarries and mines. Both artists catalog the damage incurred by humans exploiting the natural resources of the planet, but while Burtynsky’s landscapes have a sharp angularity to them, Hanson’s terrains have a dreamy grandeur, as in his image of the Yankee Doodle Tailings Pond. The beauty of the photograph belies the contents of the pond, which is filled with poisonous mining waste. Hanson noted that in 1995, 350 migrating snow geese were found dead in the nearby Berkeley Pit.

Hanson said his hopes for the book were summarized by the writer Wendell Berry:“It is unfortunately supposable that some people will account for these photographic images as ‘abstract art,’ or will see them as ‘beautiful shapes.’ But anybody who troubles to identify in these pictures the things that are readily identifiable (trees, buildings, roads, vehicles, etc.) will see that nothing in them is abstract and that their common subject is a monstrous ugliness. … If some of these results look abstract—unidentifiable, or unlike anything we have seen before—that is because nobody foresaw, because nobody cared, what they would look like.”

By mapping the environmental disasters in our country while preserving the beauty that remains in the altered landscapes, he allows the viewer to understand the loss while instilling a sense of nature's persistence.