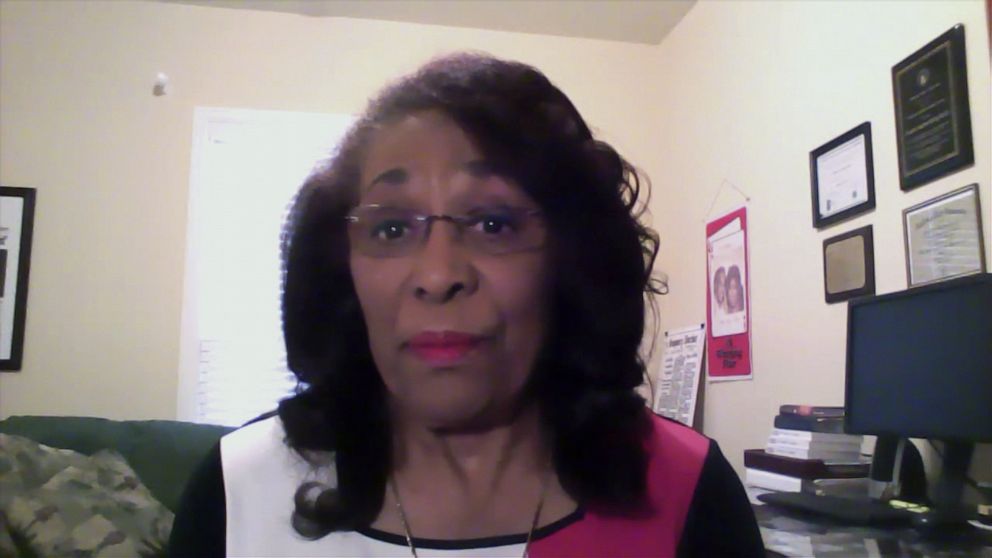

Woman whose father was lynched in 1947: Time for US to 'acknowledge our sinful past'

"The people are now suffering as I suffered," Josephine Bolling McCall said.

Josephine Bolling McCall was 5 years old when her father was shot dead by a group of white men in Lowndes County, Alabama, in 1947.

Decades later, she says the killings of black people like George Floyd and Breonna Taylor by law enforcement are “modern-day lynchings on TV,” and that they have opened old wounds, reminding her of when she was a child.

“I think of myself as a 5-year-old who came home expecting a father to come home to me, who never came back because he had been lynched,” McCall, author of the book “The Penalty for Success,” told “Nightline.” “I think the people now, the suffering they are going through because they have no protection. We don’t have equal protection under the law, and so, the people are now suffering as I suffered, and I think it’s time for a change.”

McCall’s father, Elmore Bolling, was a successful entrepreneur who owned a store and trucking company. McCall said he was also a philanthropist who invested in his community. He was killed near his store by a group of white men who shot him seven times. One of them, Clarke Luckie, said Bolling had insulted his wife during a call.

“My father was an entrepreneur and that was the reason he was killed because it was deemed that he was too prosperous as a negro,” McCall said.

Elmore Bolling’s name is the 16th name representing those killed in Lowndes County at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice -- also called the lynching museum. A project by the nonprofit Equal Justice Initiative, the group documented more than 4,400 lynchings between 1877 and 1950. To commemorate those lost to lynching, the group collected soil samples from thousands of lynching sites around the country and put them in jars labeled with the names of those who were killed.

McCall said the current moment, in which protests against police brutality have persisted for weeks, is in some ways linked to the past of the United States.

“It is time for Americans to face the present by acknowledging our sinful past,” she said. “Let’s start having deep, hard conversations on race and racism.”

She said the Senate needs to pass the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, which would increase the penalty for those who commit certain civil rights violations. The bill, already passed in the House, has been held up in the Senate by Rand Paul of Kentucky, who has expressed concern that it could allow minor confrontations to be punishable as lynchings.

But one of the bill’s authors, Senator Kamala Harris has argued that Paul’s suggested changes to the legislation "would weaken" the bill and put a "greater burden on victims of lynching than is currently required under federal hate crime laws."

For McCall passage of the bill would give her and others experiencing similar pain a chance to move forward and heal.

“People need to begin to recognize us for who we are, respect us as human beings, and that is what we’re being denied, the right to be a human being, really,” she said.

“National issues require national action. An antilynching bill has been on the table ever since 1898 with Ida B. Wells,” McCall added, referring to the black journalist who in the 1890s went on an anti-lynching crusade. “I was 5 years old when my father was lynched. I am now 77 years old and we still don’t have any antilynching legislation. As long as there are no consequences for such terrible crimes, then we will not have any cessation of those actions.”

McCall, who still lives about 25 miles from where her father was killed, said she is still “hopeful.” She said that if her father, a religious man, were still alive today, he’d be trying to “explain the nature of having to live together peacefully by working together to engage in projects together. That would be the way that he would try to help everyone obtain success.”