Early Peanut Exposure May Reduce Allergies, 'Game-Changer' Study Finds

Experts call new peanut allergy prevention study a "game-changer."

— -- "Read the 'gredients!" Jill Mindlin's daughter used to say when she was a toddler, running around the kitchen and holding up the food she wanted to eat.

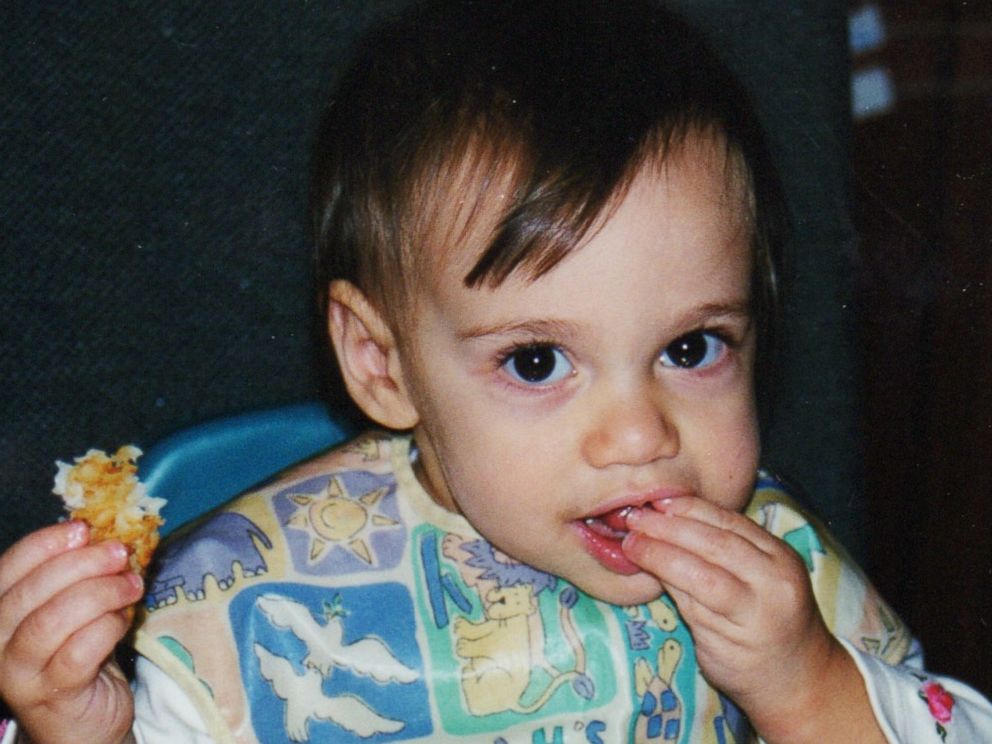

At 3 years old, Maya already knew that if an adult didn't read the ingredients, she could have a deadly allergic reaction to the food she ate, Mindlin said. The first time Maya went into anaphylactic shock, she was just 9 months old, and doctors soon learned she was allergic to peanuts, tree nuts, eggs, dairy and sesame seeds. Like most parents, Mindlin wondered if it was her fault.

"Could I have done something differently?" Mindlin remembers thinking. "Why is this happening to her?"

Peanut allergies in particular have doubled in the last 10 years, so a team of researchers with funding from the National Institutes of Health and the nonprofit group Food Allergy Research and Education set out to see whether early exposure to peanuts played a role in developing peanut allergies.

They followed hundreds of children from the time they showed a slight sensitivity to peanuts -- between 6 and 11 months old -- until they were 5 years old. Those who avoided peanuts were more likely to develop full-blown peanut allergies than those who didn't, according to the study published today in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Only 1.9 percent of those who were exposed to peanuts early developed the allergies compared with 13.7 of those who developed allergies after avoiding peanuts, the study showed.

Dr. Stacy Dorris, an allergist and immunologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee, called the study "exciting." Dorris was not involved in the study, but said prior to 2008, parents were told to avoid feeding their children peanuts until they were about 2 years old. That year, evidence in Israel began to hint that perhaps early exposure to peanuts might prevent the allergies, she said.

"I think it's really going to be a game-changer for the allergy world," said Dr. Samuel Friedlander, an allergy and immunology specialist at the University Hospitals in Cleveland, who was not involved in the study. "Up until now, we've been focused on diagnosis and management of children that have food allergies. This is the first randomized, controlled study that gives us evidence that we can prevent the occurrence of food allergies in kids. It would be much easier for us to be able to prevent the development of food allergies in the first place."

Mindlin's daughter Maya is now nearly 14 years old and doing well. While any new research is positive, Mindlin said she has some advice to parents: Don't feel guilty.

"We were told for so many years to avoid the allergens, and now the science turns around 180 degrees," she said. "You're darned if you do, you're darned if you don't. Let go of the guilt."