'They Called Me Their Get': British Filmmaker Describes Being Held by Same Taliban Group as Bowe Bergdahl

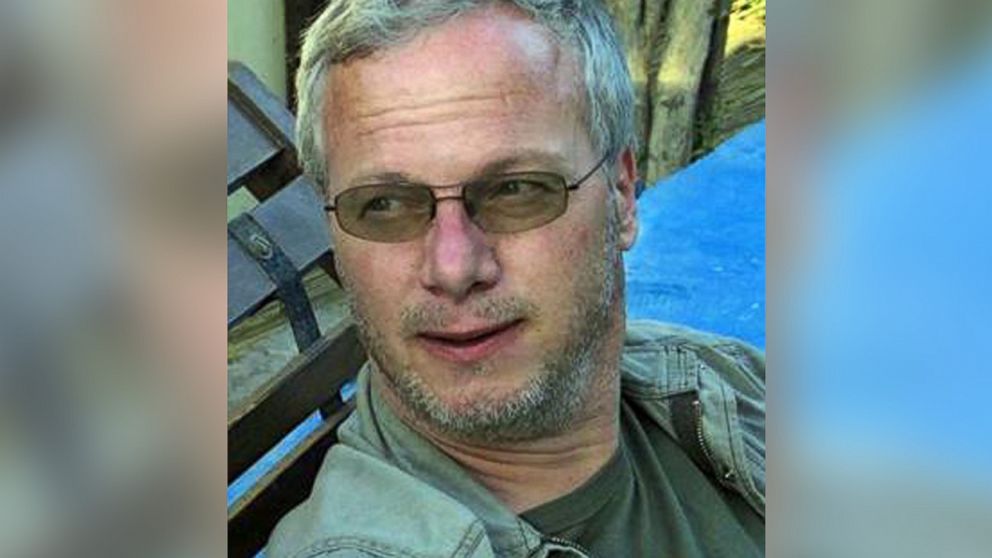

Sean Langan was held for almost four months in 2008.

June 2, 2014— -- For soldier Bowe Bergdahl, freedom is complicated, and few can imagine what he endured under Taliban captivity.

Except for Sean Langan.

“The called me their ‘get,’” he said.

The British filmmaker was held for three and a half months in 2008 by the same Taliban group that held Bergdahl for five years.

“The real struggle is not captivity, it’s when you’re released,” Langan said. “That’s when the real struggle begins.”

Langan said he was kept in a farmhouse, a Taliban safehouse, where he and his translator were locked in a dark room.

“It was dark, because they boarded up the windows, no sunlight, but I was grateful that I was not in a cave, where they couldn’t guarantee our safety,” he said.

After about a week of being held captive, Langan said the commander of the group entered the room and read from a piece of paper that said Langan was accused of being a spy and working for a foreign government.

“I knew at that point I was kidnapped,” Langan said. “[The commander] showed me a jpeg. … He showed me this young boy at age 12, and the camera pans away, and the boy has a bomb belt, and the next shot is an American Humvee, and it blows up, and that’s when I realized my life was in the hands of a sociopath. Those are the people who held me and the people who held [Bergdahl].”

Then the day came when Langan said the men told him he was going to die and they were going to slit his throat.

“They came in and said ‘we’re going to execute you tomorrow,’ and I had this very calm conversation,” he said. “That almost broke me. ‘Oddly enough I have a problem having my throat cut. Do you mind if you shoot me in the head instead?’ And they had a discussion, and said ‘OK.’ And I said, ‘I want that man to shoot me’ because he had been kind to me, and I don't know what happened, but that execution never took place.”

As the days went by, Langan said he was forced to watch videos of beheadings and sniper attacks of people being killed. He said he even watched videos of Bergdahl that were used as proof that he was alive. Eventually, the family whose house he was being held in brought him a razor and a radio, which “made all the difference between sanity and insanity.”

“To survive, you need things, very small things to hang onto,” he said. “I had this radio which allowed me to hear BBC, and also there was a small hole that looked out onto the world, and that kept me going, just to be able to see something of the outside world.”

Langan was rescued in 2008 after his family negotiated a successful release. He says when Bergdahl comes home to Hailey, Idaho, it won’t be easy to leave behind the trauma of being a prisoner.

“At first, you’re so elated, being back home. You appreciate freedom so much more,” Langan said. “But then, after tasting my first salad, first cold beer, first holding my kids, I’ve never felt more disconnected from my loved ones and family. You’re filled with love, and then three months later, I would see images of death. If I’d had a gun I would have shot myself. I fought to survive for my children, and then after I fought not to kill myself.”

For months, Langan said he could only sleep on the floor with a pillow and even now, after years of being free, he said he hasn’t been able to sleep with the lights off. His PTSD started to affect his marriage and his family, and even everyday chores could become a challenge.

“During captivity I set my clock to London time, and I used to bathe my children every day at 5 o’clock. And I would kneel down, and I could see my children,” he said. “Then three months after my release, I would miss dates with my children, because I was curled up on the floor, unable to leave the apartment.”

But today, Langan has worked through some of his struggle with PTSD.

“You go from extreme connection thinking of your loved ones to extreme inability to relate,” he said. “Now, I’ve come out the other end. Lesson I learned: the irony is that it’s all about faith, family and friends. So I now spend much more time with my children than when I was a journalist traveling the world.”