'It's all gone': Hurricane-ravaged Dominica, on the front line of climate change, fighting to survive

Dominica has the highest death toll per capita after Hurricane Maria.

— -- Verlyn Peter picked her way through the wreckage of her home, searching for anything she and her family could save.

“This used to be what we call our living room,” she said, then gestured to another area she said used to be her daughter's bedroom.

“It’s all gone,” Peter said. “We tried to salvage some of the school books.”

The wooden frame and scattered belongings were all that remained of their home of 20 years on Dominica, which was ravaged by Hurricane Maria last month. Without warning, the storm rapidly accelerated from a Category 3 to a Category 5, and residents said they could do little to prepare.

In one night, life on this tiny island was turned upside down.

"There was lightning, there was heavy rain...[it was like] the hurricane was in the house," said Dominica’s Prime Minister Roosevelt Skerrit. “We have lost everything that money can buy, and that is a fact.”

Another now displaced resident named Emmanuel Peter said he can still remember the roar of the hurricane-force winds.

"It was just whistling, whistling,” he said. “I thought it would burst my eardrums.”

Many countries, including the United States, have suffered from this year’s brutal hurricane season. But the one with the highest death toll per capita was Dominica -- a close-knit, mostly Christian nation that was left at the mercy of a hurricane that shared a name with the mother of Christ: Maria.To date, 26 people are confirmed dead, 31 are still missing, and more than 50,000 people are displaced on an this island that has a total population of roughly 74,000.

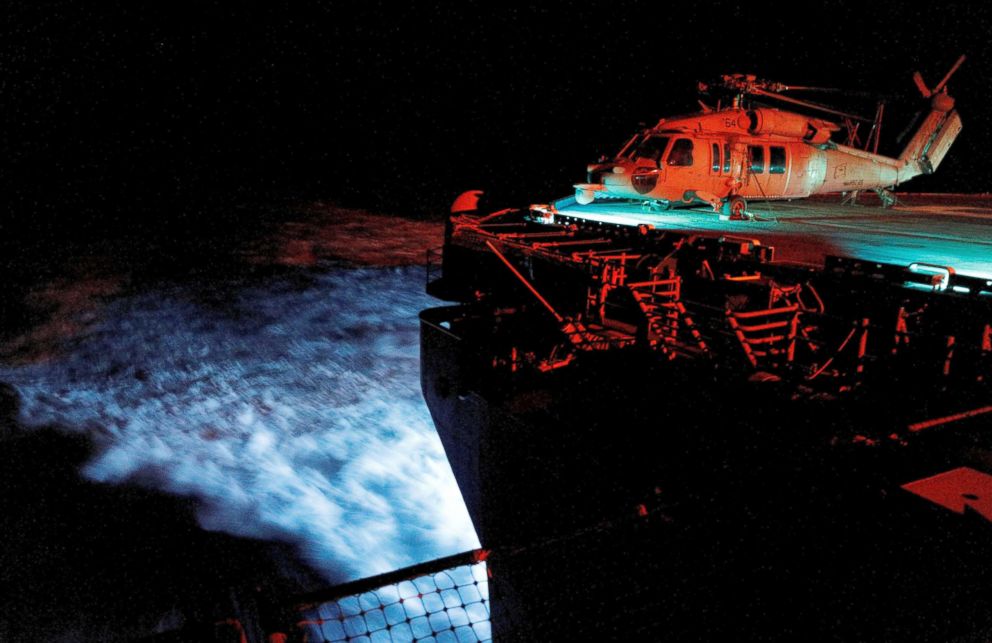

When "Nightline" visited Dominica six days after the storm, the only way to reach its interior was with the U.S. military. Upon arrival, many who had the option to evacuate the island were in the process of departing -- including 1,300 students at Ross University Medical School, an American college based in Dominica.

“I do feel sadness for the people of Dominica,” said Carey James, the college’s associate dean of operations, analysis and admissions. “My wife’s family is from Dominica … and it’s hard to see a place that you love go through that kind of a storm.”

Others who were evacuating from the island faced the difficult decision of separating their family. Gervan Honore put his girlfriend and their infant son on a ferry while he stayed back, determined, he said, to rebuild his country.

“It is hard to let him go, but as a father, you just have to do what you have to do,” Honore said. “Right now, I don’t think it is pretty safe for them.”

Hurricane Maria pummels Puerto Rico, Caribbean

No one on the island has access to running, drinkable water, and with sewage systems destroyed, residents are contending with fears of diarrhea and dysentery. Much of the island remains without power, too.

For the vast majority of Dominicans, the choice to leave their home country isn’t available. More than 85 percent of houses have been damaged, and of those, more than a quarter simply do not exist anymore, leaving many homeless.

Not even the country’s prime minister was spared – the roof of Roosevelt Skerrit’s house was blown away and its floors flooded. On the night Hurricane Maria hit, Skerrit took to Facebook to post updates including one that said, “I am at the complete mercy of the hurricane. House is flooding” and another that said, "The winds are merciless! We shall survive by the grace of God!" Later he posted, “I have been rescued.”

“You can still see the shock, the anxiety, the fear the trauma in the eyes and the expressions of people every day,” he told "Nightline." “Their entire life investments, life's savings, blown away.”

While on the island, "Nightline" also met with resident Robert Benjamin, who stayed behind with his 83-year-old mother. Benjamin showed “Nightline” their family home, which remained standing with the roof intact, but their basement had been flooded and their furniture and belongings caked in a thick layer of mud. The flood waters rose so high that they covered the counter tops in a basement kitchen.

“But we have our life and we can at least house people down here once it’s cleared,” he said. “Like I said, there’s a lot of homeless.”

A few of the rooms in the house are still habitable, and Benjamin and his mother opened their home to three other families forced out by the storm.

“They are very, very good to us,” said Ursula Peter, one of people the Benjamin family took in. “If it wasn’t for Mrs. Benjamin and her son, we would not know what would have happened to us. We all live together as one family.”

All of the island’s agriculture was wiped out, and entire forests were flattened in Maria’s wake. Tourism, a driving force in its economy, will be scarce in the months to come.

As one ferocious storm followed another this hurricane season, Skerrit told “Nightline” that his country was on the front line of climate change and that its very survival was in question. Its future could serve as a warning to the world on the destruction global warming could bring.

“To deny climate change … is to deny a truth we have just lived,” he told the United Nations five days after the storm, telling the world body that island nations like Dominica are paying the heaviest price for a phenomenon they had little to do with.

“No generation has seen more than one Category 5 hurricane. We’ve seen two in two weeks,” Skerrit told Pannell. “So if you want to have information that … climate change is a real phenomenon,

For those still on the island, trying to reclaim their lives is now the task at hand.

“How we’re going to build up again, we don’t know,” Verlyn Peter said. “But we try to keep our spirits high, because if we break down, we break down.”

ABC News' Bruno Roeber, Scott Munro and Lauren Effron contributed to this report.