Bill Barr isn’t 1st attorney general embroiled in partisan fight: COLUMN

The nation’s top cop has sometimes been the fiercest party fighter.

Has the attorney general always been so partisan? It's a question I've been hearing a lot since William Barr's pugnacious testimony in the Senate last week, followed by his showdown with the Democratic House.

It's actually a question I'm often asked about all kinds of institutions and individuals in this age of polarization. And more times than not the answer is "pretty much." Partisanship's not new on the political scene, and the nation's top cop has sometimes been the fiercest party fighter in an administration.

Despite the Democrats' insistence Barr is out of line, that the attorney general should serve as the country's lawyer, not the president's, that distinction has escaped many of the people who've presided over the Justice Department.

Presidents often choose close allies who they think will show lap-dog-like loyalty as they enforce the laws. When John F. Kennedy picked his own brother, opponents and editorial writers erupted in outrage, even more than when Dwight Eisenhower appointed his campaign adviser and former Republican National Committee chairman Herbert Brownell. Both Brownell and Robert F. Kennedy eventually received plaudits for their time in office, but no one ever doubted their loyalty to their parties and their presidents.

The current president firmly believes that's the way it should be.

Trump fumed that his first attorney general, Jeff Sessions, was disloyal for recusing himself from the Russia investigation. President Barack Obama's man in the job, Eric Holder, acted the way an attorney general should, Trump told the New York Times: "Holder protected President Obama. Totally protected him. ... I have great respect for that, I'll be honest."

And usually, presidents who expected protection got it. It's the exceptions that stand out, the men who chose to defend the Constitution instead of the chief executive.

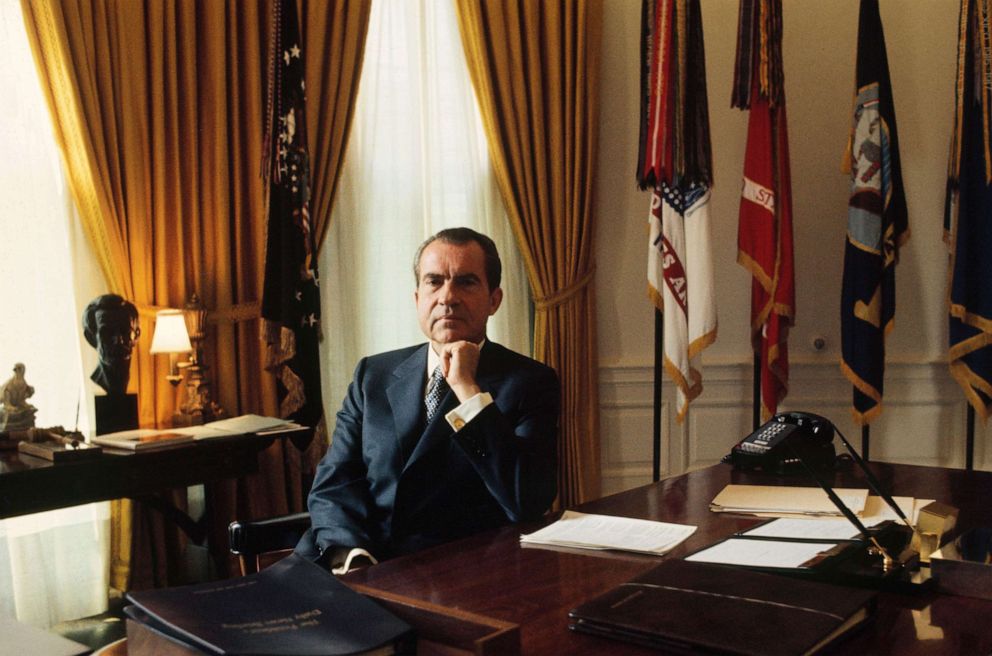

The most famous example came the night of the "Saturday Night Massacre" in 1973 when Attorney General Elliot Richardson resigned rather than carry out President Richard Nixon's order to fire the Watergate special prosecutor. When Richardson's No. 2, William Ruckelshaus, also refused the command, he was fired, leaving Solicitor General Robert Bork to do the job, which he did.

It's a more recent instance, however, of an attorney general's independence that might be more on the minds of some of the players in the current controversy. In 2004, the electronic eavesdropping program instituted by George W. Bush was due to expire and needed the legal go-ahead from the Justice Department to continue. Attorney General John Ashcroft had determined that the program was not, in fact, legal and had decided not to sign on when he went into the hospital for surgery.

That left Deputy Attorney General James Comey in charge.

When he refused to give his approval, White House operatives thought they could procure Ashcroft's signature from his hospital bed. But when they called Ashcroft's wife to say that they were headed to see her husband, she immediately informed the Justice Department. Comey rushed to the hospital to intercept the intruders and alerted the director of the FBI, Robert Mueller, to make sure that no one tried to remove him from the room. Amid this drama, the president's men arrived at the hospital, made their urgent appeal to the ailing Ashcroft and were firmly rebuffed.

The next day the administration renewed the wiretap program despite the ruling from the nation's lawyers. Ashcroft, Comey, Mueller and a few other Justice Department officials planned to resign in what would have been an even larger massacre than the one that Saturday night three decades earlier. The president quickly intervened, summoned Comey and Mueller, and changed aspects of the spy program in order to make it legal. The men remained in their jobs having also remained loyal to the rule of law.

By the time Donald Trump came to office, Comey had succeeded Mueller, who had stepped down from his post at the FBI to practice law in the private sector, taking on hot-button issues like the investigation of the NFL's handling of a domestic violence scandal. Then Trump fired Comey, and Mueller, the veteran investigator, returned to government for the thankless job of heading a probe buffeted by partisanship and under attack by Twitter from an anxious president.

This time Mueller has no ally in the Justice Department. Barr has declared that Mueller's work is done, that the investigation is now "my baby."

Like many attorneys general before him, Barr wouldn't be the first to show his partisan stripes.

Cokie Roberts is a political commentator for ABC News. Her views do not necessarily reflect those of ABC News or of The Walt Disney Co.