MLK March: Child, Photographer, Protester Were Never the Same

Edith Lee-Payne became the face of the March on Washington.

Aug. 26, 2012— -- When Edith Lee-Payne celebrated her 12th birthday just steps away from the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. as he delivered the most acclaimed and prophetic message of the civil rights movement, little did she know she would become the face of the March on Washington.

The Aug. 28, 1963, image of her face, as she listened to King deliver his "I Have a Dream Speech" framed by a protest banner, captured a slice of the demonstration in a way that still evokes the spirit of the march for both Lee-Payne and the photographer who stumbled onto her that late-summer day.

"I had a great sense of what was going on," Lee-Payne, now 61, told ABC News. "I knew I was at something important because Dr. King was there, but I couldn't yet say it was historical."

King had spoken two months earlier in her hometown of Detroit, and her mother, a "domestic" worker, had brought young Edith along as King urged others to join him in Washington.

"Dr. King wasn't just a speaker, he was a minister and he included Scripture in his message," she said. "He always spoke the truth. He had a very commanding voice and you kind of hung on to every word he said. He was very eloquent, not just how he said it, but the meaning behind it."

"I always felt within myself that no matter what the situation, if something was not right, I would say it's not right." -- Edith Lee-Payne

Lee-Payne's mother had been a professional dancer in the 1930s, traveling the South as an opening act for top black stars like Sammy Davis Sr., Cab Calloway and Duke Ellington. At the Washington monument, singer and activist Lena Horne recognized Lee-Payne's mother. They had toured together throughout the South and experienced Jim Crow laws and lynchings.

"It was the first time I learned she had experienced any kind of racial problems," Lee-Payne said. "She discussed going to theaters and having to go through the back for 'colored-only' singers and what they had seen in their travels how people were treated."

Civil rights had "not yet hit the history books" when Lee-Payne was a seventh-grader in an integrated school in Detroit, but she had followed the black press, magazines like Jet and Ebony.

"They had a lot of stories and graphic things in the news about people being mistreated and children not being able to go to school and people couldn't vote," she said. "All that was very contrary to the way I lived."

As a young adult, Lee-Payne would experience discrimination when she applied for executive secretary jobs in Washington, D.C.

"You were supposed to be type 60 words a minute, but I exceeded that," she said. "But when interviewers came into the room and they'd see a black person, they would tell me the job was filled or I wouldn't like the job.

"One person did sit me down and took the time to give me a test on the transcription machine, which at the time had earphones and foot pedals. She said, 'you should get it because black people have rhythm.'"

"My parents had been worried about violence. But the march was so dignified ... It provided a different type of aura to the civil rights movement ... a message to the larger society." -- Stephen London

But it was the 1963 march that fortified Lee-Payne's social conscience. Before she moved back to Detroit in the late-1970s, she fought to keep schools integrated in Prince George's County, Md.

What brought her as a 12-year-old to hear King speak was a "reverential respect of God," Lee-Payne said. "I always felt within myself that no matter what the situation, if something was not right, I would say it's not right."

Rowland Scherman, a 26-year-old photographer for the United States Information Agency, captured such commitment to justice in Lee-Payne's face that day on the mall. She was standing at the front by a fence, just to King's left as he looked out from the stage on an estimated 250,000 marchers.

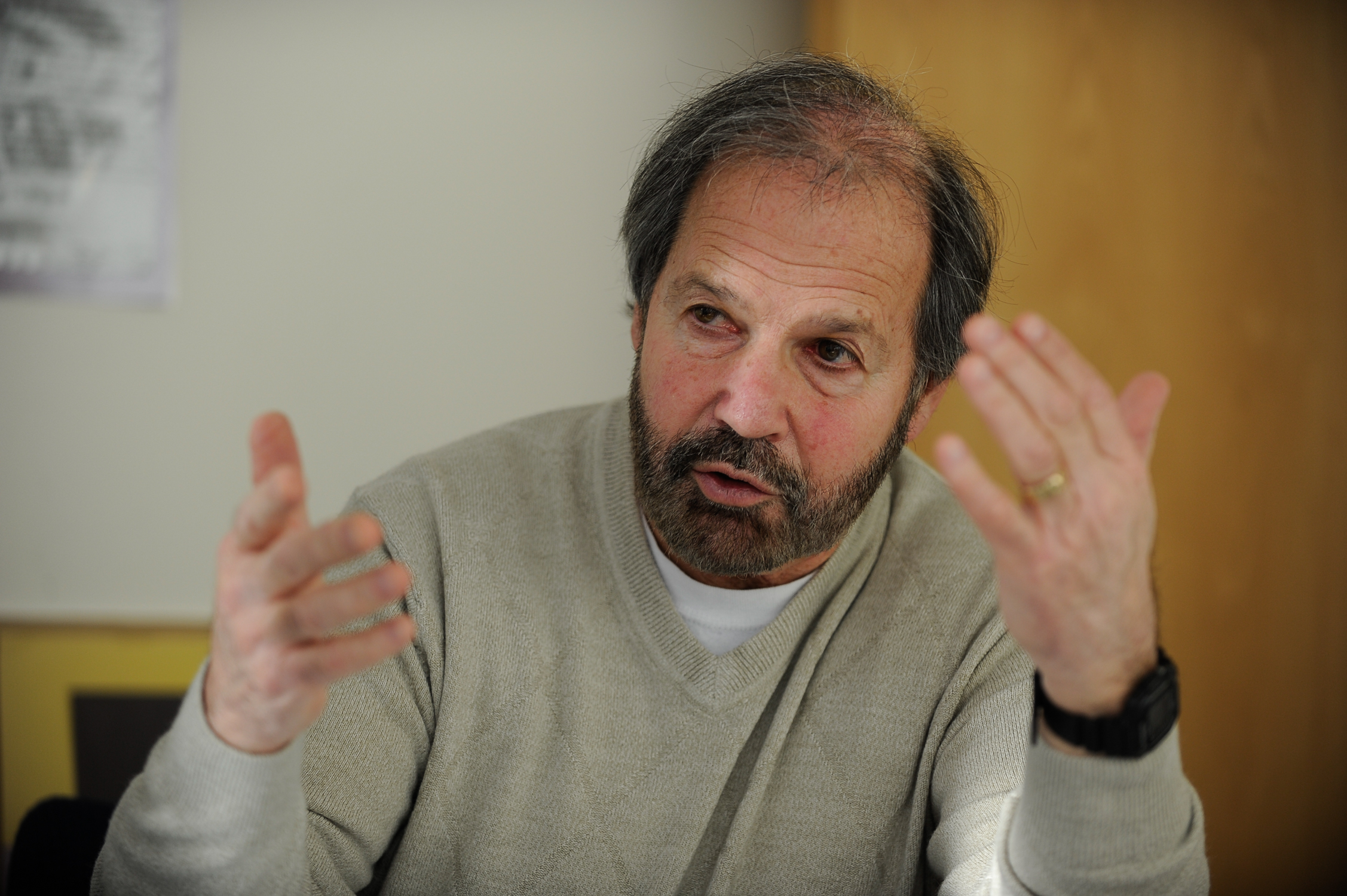

"It was astounding," Scherman, now 76, said. "Here I am a cub reporter, and literally my first real assignment turns out to be the biggest event in American history."

Lee-Payne said she only learned of the existence of the photo five years ago when her cousin was looking through a catalogue of calendars and recognized Payne's childhood photo on the cover of one.

"I didn't know it had been taken," Lee-Payne said. "Why would a picture of me be on a black history calendar? I thought she was joking. I was in absolute denial because I couldn't believe that was me."

When King took to the stage, Scherman was whisked away, but it was then he saw Payne.

"I turned around and saw this beautiful young woman listening to Dr. King," he said. "She was so interested and enrapt by the events. I didn't realize how terrific the picture would be."

Learn everything you don't know about Martin Luther King Jr.

The BBC brought the pair together in April to walk around Washington's reflecting pool where marchers stood their ground.

"I didn't even know who she was or her name, but when I met her, she was like an old friend," said Scherman, who now does portraitures after a career in journalism and lives on Cape Cod, Mass.

That day in 1963, he said, he used 30 to 40 rolls of film: "thousands of photos."

"A lot of photographers just took positions and that was the spot where they stayed all day," he said. "I had amazing access to everything because I was an official U.S. government guy. I ran everywhere, took photos of Joanie [Baez] and Bob [Dylan] and Martin Luther King when the march started. I climbed up the top of the Lincoln Memorial and took the big shot."

That shot captured hundreds of thousands of peaceful demonstrators whose consciences had called them to Washington. One was Stephen London, a 20-year-old student from Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine. He boarded a bus organized by the NAACP that was filled mostly with white protesters.

"For me, it was a very emotional experience," said London, who is now 70 and a sociology professor at Simmons College in Boston. "I had come from a somewhat isolated university in Maine where I was often the lone voice on these issues. And here, I was surrounded by thousands and thousands of like-minded students."

London was positioned relatively close to the monument itself and remembers King's "incredibly moving" speech vividly, not knowing "its significance over time."

"I remember being just overwhelmed with the magnitude of the scene and the numbers of people," he said. "The most significant impression of the march was the engagement of the clergy. For me it has always been not just a social justice issue, but a moral issue."

The spring after the march, London met King at his college. "Someone asked him the significance of the march and I remember him saying that before the march, he didn't have access to the White House," London said. "Afterward, he did through Kennedy's brother [Robert F. Kennedy], the attorney general."