NC Community in Months-Long Battle to Bring Home Undocumented Teen, Despite Election-Year Controversy

After almost seven months in jail, $10,000 was raised in two days.

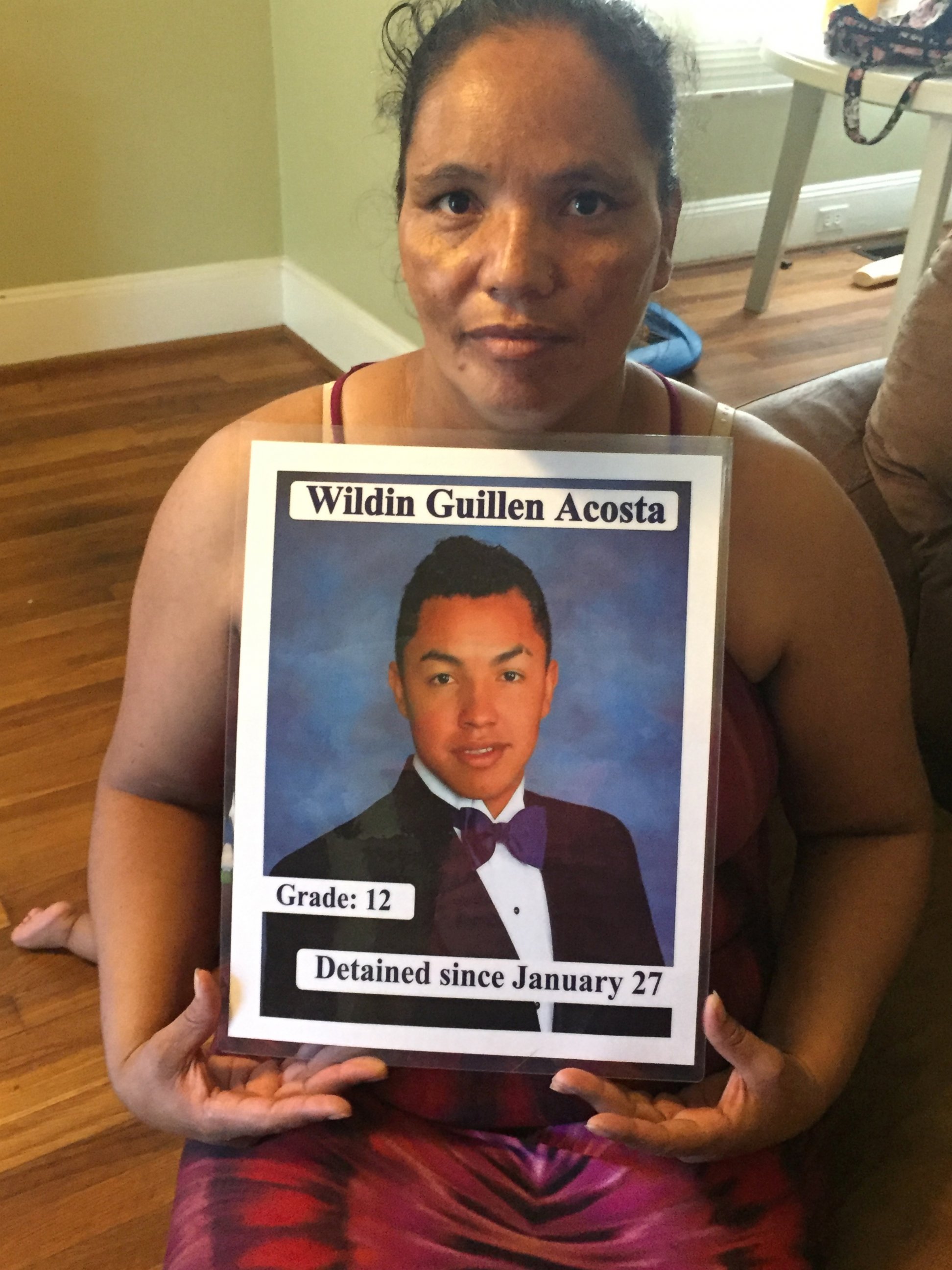

— -- When high school senior Wildin Acosta stepped outside his North Carolina home on a frigid morning this past January, his mother was watching through the window to send him off to school at Riverside High School in Durham.

She then saw federal agents confront her 18-year-old son.

The agents, who were with the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), took Acosta into custody, in keeping with the latest Obama administration priorities regarding immigration enforcement.

After almost seven months in a Georgia prison, Acosta was released over the weekend -- not back to Honduras, but to a U.S. community that rallied behind one of its newest members, fighting a deportation order, and raising thousands of dollars to cover the legal expenses for his release.

Acosta’s story is that of a young man caught between violence in Central America and opportunity in a country that has grown increasingly polarized over the presence of immigrants -- and the benefits or harm that they bring.

It’s a story that begins almost three years ago, with a plot that could take several twists in the coming months amid a presidential campaign loaded with rhetoric about immigration policy.

Fleeing Honduras

In the early months of 2014, Acosta's mother, who was living in Durham, said she started receiving phone calls from her son, who was living in Honduras.

Dilsia Acosta told ABC News that her son was begging her to figure out a way to bring him to the United States. He felt his life was in danger, she said through a translator, a community organizer advocating for Acosta and his family.

She recalled her son saying that two gangs -- Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and the 18th Street Gang -- were attempting to recruit him but that he didn't want to join.

Those two gangs are major contributors to the violence that has made Honduras the country with the highest homicide rate in the world according to the World Bank, forcing thousands to flee their homes. The government of Honduras, according to the United Nations' refugee agency, estimates that 174,000 people were internally displaced within the country between 2004 and 2014 because of violence and insecurity.

Others, including Acosta, have fled north through Mexico, to the United States.

“He came here essentially fleeing from their threats, because if he didn’t join the gang, most likely he would be killed,” Dilsia Acosta said.

In a surge of undocumented immigration that captured the nation’s attention for several weeks during the summer of 2014, Acosta and tens of thousands of migrants, many of whom were unaccompanied children, headed north.

According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection statistics, between October 2013 and September 2014, nearly 63,000 unaccompanied children were apprehended attempting to cross to the United States.

While the status of those children is likely still being determined in the eyes of U.S. immigration law, we do know that in the four years leading up to October 2015, ICE removed more than 7,000 children who had crossed into the United States unaccompanied.

Over the year-and-a-half after his arrival, Acosta settled into American life, his lawyer told ABC News.

By the time he was apprehended, “he already had an afterschool job and he had a B-average in mainstream classes -- in classes that were given in English,” Evelyn Smallwood said, noting that Acosta did not speak much English when he arrived.

Immigration Battle in Washington

As Acosta was making his way through Mexico and across the southern U.S. border, efforts to reform the U.S.’s immigration system were stalling.

In June of 2014, after a year of wrangling, Democrats in the House gave up on passing a comprehensive immigration reform bill to match one that the Senate had passed the year before.

In response to the failed immigration reform attempt, five months later, in a 15-minute televised address from the White House in November, President Barack Obama announced sweeping executive action on immigration.

The centerpiece of Obama’s unilateral reforms was a program called Deferred Action for Parents of Americans (DAPA), which was intended to allow the undocumented parents of American citizens to remain in the country temporarily without fear of deportation. It has since been halted by court order, as several states have challenged its constitutionality.

However, another, less-publicized component of the reforms, was the reprioritization of deportation to focus on individuals who had arrived in the country as of the beginning of that year.

While the White House often billed the deportation reprioritization as “deporting felons, not families,” it made any undocumented immigrant who came to the United States after Jan. 1, 2014, a priority for removal, unless that person qualifies for asylum or has another legal reason for remaining in the country.

That included Wildin Acosta, who had been in the country for only a few months. According to his lawyer, who began representing him after he was apprehended, Acosta later failed to appear for a court date, causing a deportation order to be issued against him.

As Deportation Looms, a Community Rallies

As of March of this year, some 57 percent of all registered voters in the U.S. “say that immigrants in the United States today strengthen the country because of their hard work and talents,” according to the Pew Research Center.

However, views on immigrants don’t appear to be as warm in North Carolina.

A 2013 study by researchers at the University of North Carolina suggested that the “majority of North Carolinians who were surveyed viewed immigration as a threat,” and “eighty percent of North Carolinians surveyed supported deportation of illegal immigrants.”

Despite apparently strong views against undocumented immigration in North Carolina, Acosta quickly won support from his community.

Just days after Acosta was apprehended and transferred to the Stewart Detention Center in Lumpkin, Georgia, the city of Durham's Human Relations Commission passed a resolution calling on ICE to stop deportations in the community, according to the News and Observer.

By mid-February, as the threat of deportation to Honduras loomed, ABC's Raleigh-Durham station WTVD reported that community members began rallying behind the teenager.

Despite pending appeals in his case for asylum, the process of deportation proceeded, and he was scheduled to be sent back to Honduras on March 20, 2016.

The deportation was halted by the eleventh-hour intervention of U.S. Rep. G.K. Butterfield.

“When the order of deportation was beginning to be enforced, the Durham community became united and supportive of Wildin and they approached me about offering my support,” Butterfield told ABC News.

“I had not really heard of the case before they came and brought this to my attention, and once I looked into it, I found it was a very deserving case and it’s unique because it’s not just an immigration case, it’s a plea for asylum,” Butterfield explained.

Eleventh-Hour Negotiations

With 48 hours to go before Acosta's deportation deadline, protesters descended on the congressman’s office begging his intervention on March 18. Butterfield said that ICE Director Sarah Saldaña had assured him she would make a decision on Acosta’s deportation by the end of that day.

Seeming heartbreak came that night, when Butterfield said that he had received word from Saldaña that -- after she personally reviewed his case -- the deportation would proceed.

Disappointed that the last-minute decision meant that an appeal couldn’t be heard until Monday -- the day after he was scheduled to be deported -- Butterfield continued working through the night.

A breakthrough came on Sunday, the day Acosta was set to leave.

"This morning, ICE Director Sarah Saldaña issued an order preventing the deportation of Wildin Acosta until the legal process can take place in an orderly manner,” Butterfield said in a statement at the time.

With the threat of immediate deportation behind him, Acosta remained in the jail in rural Georgia for five more months waiting for appeals in his asylum case to proceed.

During this time, he was visited by supporters, including Butterfield.

“During my meeting with him, he expressed an interest in returning to continue his education,” the congressman told ABC News. “He was trying to hold up under the circumstances. Obviously he wanted to reunite with his community and family.”

$10,000 in Two Days

A chance at that came in early August, when Acosta’s lawyers and ICE agreed to a bond of $10,000 that was approved by a judge early last week, according to Smallwood, Acosta’s attorney.

Supporters created a fundraising page on a popular crowdfunding website, hoping to raise the required amount.

Within two days they had met their goal, and the donations kept coming. The campaign has raised over $11,800 from 310 contributions so far, ranging from as little as $5 to more than $100. Some are anonymous, others have left their names and words of encouragement.

“It is way past time for Wildin to be home,” wrote a person identifying herself as Lynne Walter, who gave $100. “We're all looking forward to welcoming you back!”

“So excited that we are winning this fight!” wrote a donor identified as the Rev. Julio and Martha Ramirez. “Can't wait to see Wildin graduate!”

“Come home, Wildin,” wrote a person naming themselves as Vicky Kim.

Reacting to the rapid fundraising campaign, Butterfield told ABC News, “I was not surprised. I know that the broad support that Wildin has in Durham -- it comes from teachers, and students, and political leaders, and just average citizens who have compassion for this young Honduran kid.”

When asked about the mother’s reaction to the outpouring of support, the translator told ABC News, “She’s very happy, very emotional as well, because she’ll be able to hug him again, to be able to touch him again, and to regain all this time that’s been lost in the last six months.”

Weekend Release and an Uncertain Future

Their wishes were granted Friday night, when he was released from the detention center in Georgia.

“Dilsia Acosta, Wildin's mother, and members of Alerta Migratoria NC were there waiting with open arms to receive him and bring him back to his home in Durham,” the immigrant activist group said in a statement posted to Facebook.

The group said that Acosta is now home with his family in Durham.

While they are celebrating his release, Acosta’s future is uncertain.

With a pending asylum case before the courts, it is still conceivable that Acosta will be found undeserving of asylum under U.S. law, and will be returned to his home country of Honduras.

“I’m optimistic, [but] he still has the burden of proving that he is deserving of asylum status,” Butterfield said.