Jose's Journey: One Unaccompanied Minor's Escape From Violence and Redemption in America

Jose left Honduras and found a loving foster family in Michigan.

— -- Pete Homeyer had never served tamales at Christmas dinner at his house in Michigan before, but last December the classic Honduran staple was placed right next to the roast beef to help make Jose, a foster child who arrived in America as an unaccompanied minor at age 16, feel more at home.

Jose, now 18, had spent the previous Christmas in a holding facility in Texas after escaping violence in Honduras.

Homeyer, a 46-year-old nonprofit consultant in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and his wife Lynne, a 61-year-old Web editor, had no connection to Jose or Honduras before last year.

"When he came here, he didn't speak any English at all,” Pete Homeyer told ABC News. "He knew his numbers and his colors and ‘yes' and ‘no' and not a whole lot more than that.”

Now, after living with the couple for 18 months, Jose has done "very well” academically, transitioned out of his school's English as a Second Language classes, is helping design the class ring and played for the varsity soccer team.

"Soccer is like free time for me, where my mind does not focus on missing my family and friends in Honduras,” Jose told ABC News.

Jose was one of the lucky ones.

He is one of the tens of thousands of minors who have arrived at the U.S. border without legal documents, and without adult relatives for support. The wave of unaccompanied minors reached tsunami-like proportions this summer, with 67,339 children arriving in the U.S. in need of care through Sept. 30, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

While most children are placed with a parent or extended relatives who already live in the U.S., a much smaller portion of these children are sent to live with American families who have offered to take unaccompanied minors in. The Homeyers are one such family, having heard about the plight of these children through a Christian charity and deciding to help.

"I'm happy that in the life of one person, they could be offered something more,” Pete Homeyer said.

Escaping the Violence

Jose is reluctant to speak about the dangers he was facing in Honduras, but the American government knows what was in store for him, like so many teenage boys in the region: the State Department has reported that Honduras has had the highest per capita murder rate in the world since 2010, with gang violence as one of the leading factors. "He tells me that he and his friends were all being pressured to join gangs,” Lynne Homeyer said.

The Homeyers try not to focus on the trauma from his home life and Jose saves talk of the specific threats for his quarterly court appearances when he has to plead his case. "He was in danger there. He was in physical danger living in Honduras,” Pete Homeyer said.

Instead of looking back, Jose is constantly looking forward to what he hopes is a promising future where he can make his trips to Western Union to wire money home even more frequent than it was this summer when he was working construction jobs. He speaks to his mother and sister by phone every week.

"Sometimes the phone call is difficult because I hear about problems I cannot help them fix,” Jose said, communicating with ABC News via email with the help of his immigration attorney. Jose did not originally plan to be in this new country alone, having made the treacherous journey to America with his cousin.

"He came across the border with his cousin but the coyotes usually don't let the kids go together,” Lynne Homeyer said, referring to the human traffickers. "[Jose] got picked up at this house were a whole bunch of people were being held at gunpoint by coyotes.”

Jose's cousin escaped the home and capture, making it to Miami while Jose was transferred to a detention center run by Customs and Border Protection, Lynne Homeyer told ABC News. "He would lie in bed in the detention center and talked to God, saying ‘God, why didn't you let me get to Miami?'” she said. "[Jose] knows that his situation is so much better because now he's legal.”

Since the federal government was overloaded with the crisis this summer, struggling to find emergency shelter and fending off political immigration reform posturing, a number of nonprofit and religious groups stepped in to help provide legal counsel for some of the children.

After speaking to a number of such groups, ABC News heard about Jose and the Homeyers, and they agreed to speak about how they made their unconventional setup work under the condition that his last name would not be published.

While Jose was looking for a home, a new start in life, the Homeyers were looking for a sign. After deciding against having children early on in their 18-year marriage, the couple had been happily living their lives as "great aunts and uncles.” They had no tangible connection to the unaccompanied minors crisis but just realized that they had time, space, and the savings that two incomes amassed to take on a cause.

"We talked about how we're leading happy, shallow lives. We both kind of agreed that it would be great if we could find something that would be good for the world together,” Lynne said of a conversation she and Pete had over pizza in their furnished basement one Friday night in late summer 2012. Two days later, at Sunday services at the Episcopalian church they attend, they saw a notice from Bethany Christian Services, a charity with a base in Michigan that has been helping place refugee children with foster families since 1957.

"That was God bonking us over the head,” she said.

They spent the fall of 2012 taking state-mandated courses for any prospective foster parents, passing home visit inspections. And then they waited, expecting to be placed with a child around Christmas. Lynne said that during that time, they began to mentally prepare for their family's new addition, and the chance that the child could have a rough transition to America, leading to acting out. She said that she began saying a prayer that her sister-in-law told her: "Bless us God, and please don't let the adoption agency give us the wrong child because we're going to say yes.”

Jose arrived at the Grand Rapids airport on March 5, 2013, and the Homeyers were there with a handmade sign saying ‘Welcome Jose' flanked by an American and Honduran flag on either side.

The Human Waves of Children Crossing the Border

The number of unaccompanied minors has been steadily increasing since Jose arrived in early November 2012. Customs and Border Protection reported that this June alone, there were an average of 354 children arriving every day.

"Typically these kids are not crossing at a formal port of entry,” said Ruthie Epstein, an immigration lobbyist for the American Civil Liberties Union. "What's typically happening for these kids, which is quite unusual, is they are looking for a government official to turn themselves in. They're seeking a government official for safety.”

Jose's home country, Honduras, had the highest number of children fleeing to the United States this fiscal year, with 18,244 arriving at the border by Sept. 30. Guatemala, El Salvador and Mexico followed with 17,057, 16,404 and 15,634 children respectively, according to Customs and Border Protection.

"Conditions are deteriorating in those countries and the number of children coming to the U.S. seeking safety will not decrease until the conditions in their home countries stabilize,” Jennifer Podkul, a senior program officer for the Women's Refugee Commission, told ABC News.

When they arrive at the border, the children are held in CBP facilities made up largely of offices, processing spaces and holding cells, though they have been filling rapidly and the backlog of cases leads to dramatic overcrowding, Epstein explained.

"It's not designed to hold people for more than 12 hours and that's adults -- there's no showers, a kitchen for food preparation, no bedding or beds,” Epstein said. "CBP has been forced to hold kids in those facilities for far longer than is permissible under the law.”

Deportation proceedings are immediately launched for each of the unaccompanied minors as soon as they arrive, but that process is a lengthy one. Immigration courts are packing court schedules so tightly that they're being called "rocket dockets,” Podluk noted, though a deputy assistant attorney general for the Department of Justice objected to the use of this term during a hearing in early September.

"No one's given an attorney in immigration court -- you're allowed to bring one at your own expense and that's the same for adults and children. It's outrageous for adults but it's absolutely absurd for children,” she said. "Just by telling somebody ‘you might get deported' or ‘you're going to get sent back really quickly' -- that's not going to deter these children who fear for their safety.”

The American Civil Liberties Union filed a temporary injunction against top Justice Department officials to pause the deportation hearings of eight specific unaccompanied minors cases until they had time to find legal representation. Their legal filing states that in nearly 60,000 cases, of the children that had legal representation, 47% were allowed to stay in the United States while only 10% of the children without representation had the same outcome.

"There is no question that, as a policy matter, the Department [of Justice] would like children in immigration proceedings to have counsel. But the issue in the pending litigation is quite different, and involves only whether there is a constitutional right to government-funded counsel,” a Department of Justice spokesperson told ABC News in response to the ACLU lawsuit.

At the height of the influx of unaccompanied minors this summer, President Obama called for immediate immigration reform. Fights over budgets and politics led to a delay on his request for additional emergency funding for the Department of Homeland Security, which oversees Customs and Border Protection. The issued was initially tabled until after the summer recess, but now he has announced that immigration reform won't come up for debate until November -- after the midterm elections.

The injunction, filed in Seattle District Court, has since been denied on the grounds that the children were not facing immediate court dates, but the ACLU had also pushed to turn their case into a class action lawsuit against the DOJ. They hope to have a ruling on behalf of all unrepresented minors in immigration court, including unaccompanied minors, rather than just the eight explicitly stated in the suit. The ruling on the class action has been deferred.

This lawsuit is far from the only front where this issue is being addressed, but no one solution is expected to solve the problem completely. The Department of Health and Human Services recently allotted $9 million towards getting legal representation and help for some kids, but that is only estimated to help 2,600 children. That would mean less than 4% of the children who have arrived so far this fiscal year.

Unlike Jose, the eight children included in the ACLU lawsuit were all eventually placed in the care of relatives or family acquaintances who already live in the U.S. after having been in the custody of CBP once they reached the border. From there, unaccompanied minors are passed on to the Office of Refugee Resettlement, which is responsible for identifying an individual to take the child in. Those who do not find a home with someone they know end up either being placed in foster care or spending the remainder of their legal proceedings in ORR's custody, which could drag on for more than a year.

Jose's Journey Continues in America

Pete Homeyer said that Jose was in a holding facility in Texas for about five months before being placed with them in March 2013. They have helped retain a lawyer for Jose and he has since been awarded a Green Card but that is not the end of his immigration battle. Jose still has monthly court appearances for status updates in the case and is effectively in a probationary period of sorts called Young Voluntary Foster Care, run through the federal Fostering Connections initiative, until he turns 21.

"Jose has worked through a tiered oversight process since arriving in the US. … In each tier, Jose has received slightly more independence and less direct oversight,” Pete Homeyer said. "Although this process might seem cumbersome I believe it has worked well in the only case I know, ours. In no way has Jose simply been turned loose but carefully monitored and assisted toward a status of full independence as an asset to our country.”

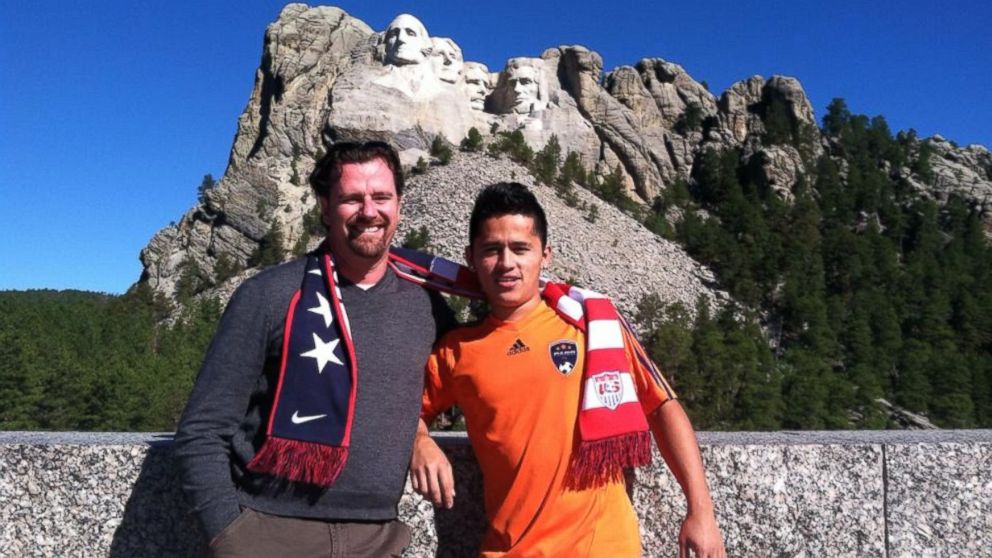

The Homeyers have made a point to show him his new homeland, starting with the Capitol Building and all of the monuments in Washington, D.C., and then taking a two-week "classic American driving trip,” as Pete Homeyer called it, to Mount Rushmore, the Badlands, the Tetons and Yellowstone National Park.

"We had three drivers since Jose can drive now. We played the license plate game. We weren't singing ‘99 Beers on the Wall' but just about everything else,” Pete Homeyer said.

"We both believed that everyone has a right to a nurturing, protective family life and there are just places in the world where those families cannot provide that right now because of war, because of government inefficiencies,” he told ABC News.

Because Jose is now 18 and has a Green Card, he no longer needs a legal guardian though that doesn't put an end to anything except on paper.

"Technically we're not his anything anymore. We're his landlords and his quasi-foster parents,” Pete Homeyer said. "I think of him as my foster son and I will always think of him as my foster son.”

The Homeyers specifically asked to be placed with an older child -- Lynne joked that way they would be "fully formed” when they arrived at their house -- but that also meant that they knew Jose was fully aware of the family he had left behind. Lynne said that she used Google Translate to help explain the situation when he first arrived home from the airport, knowing barely any English.

"I tried to say ‘I know I am not your mother and I am not your family but we are who you have now and I promise we will do all we can to help you grow and be successful in America,'” she recalled typing.

For his part, Jose is proud of himself -- of his driver's license, of his green card, of the fact that his English has improved so much that now he is "in the regular classes and making new friends.”

He was dealt a minor setback earlier this fall when he tore his ACL during one of the season's opening games, meaning that he's had to trade the soccer field for physical training sessions, but he remains focused on his goal: to send money home to his family.

"I am proud of what I have done but think about my family and how far the money you can make here, even $8 and hour or $9 an hour, can help. [In Honduras] life is a struggle to find enough money for food, clothes or to pay the bills,” he said.

When he left Honduras, Lynne estimated that Jose had the equivalent of an eighth-grade education and now "he's not really quite in 11th grade.” They just hope that he can complete high school before he turns 20, which is the legal cut off for public education in Michigan.

Jose, like all juniors at his high school, took the ACT test earlier this month. Pete Homeyer said that they've been able to carry over some of his credits in Honduras, so with the help of afterschool tutoring that he's interspersing with physical therapy sessions to help heal his ACL, they're optimistic about a June 2016 graduation date.

"For me, that would be like winning the lottery,” Lynne said.

There's another milestone that the family is looking forward to -- Jose most of all: he's going home to Honduras for Christmas this year. Because of his green card status, he is able to legally visit his relatives in his home country and return in time for the next school term. That legal status is a precious achievement for someone in Jose's position, as there are thousands of children who are sent back even if they have been placed with families or gone through months of legal wrangling.

"Jose is a great kid but the line between the success story and the failure story … is very thin,” Pete Homeyer said. "You know, think about your own life. Think about the number of times one or two things could have changed or been different and how different your life could be.”