How the proposed billionaires' income tax would work

Democrats have proposed the tax to raise money for the infrastructure bill.

A proposal to levy a new tax code on America's ultra-wealthy has sent shockwaves through the nation's capital and beyond on Wednesday, as lawmakers struggle to reach an agreement over how to pay for President Joe Biden's trillion-dollar Build Back Better initiative.

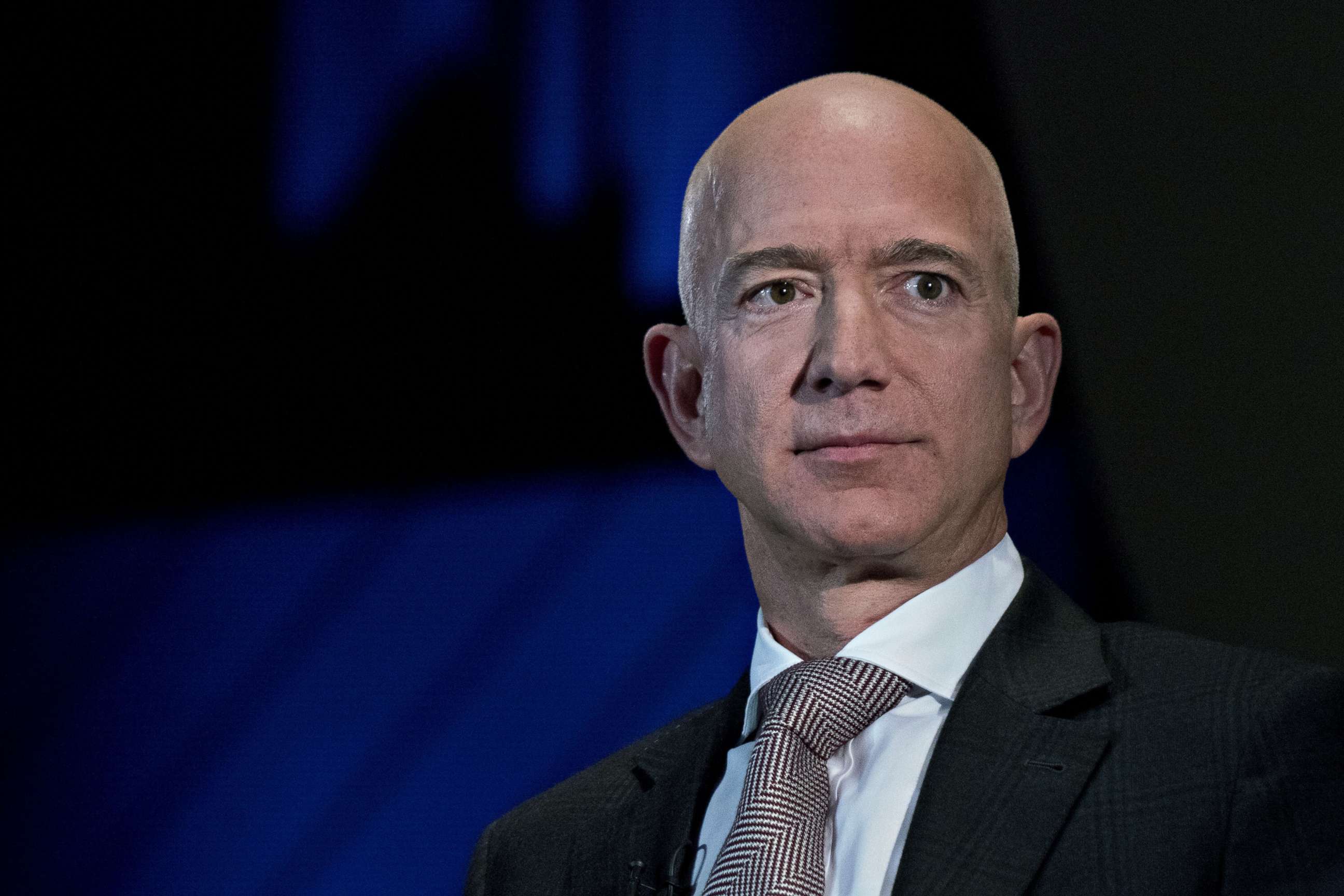

Senate Finance Committee Chairman Ron Wyden, D-Ore., on Wednesday morning unveiled a scheme dubbed the "Billionaires Income Tax," which would tax capital gains on the unsold assets of billionaires -- such as stocks -- and significantly impact some of the nation's wealthiest people, such as Amazon founder Jeff Bezos and Tesla CEO Elon Musk. Musk, whose net worth is currently $287 billion per Bloomberg's real-time data on billionaires, signaled on Twitter that he opposes the proposal.

"Eventually, they run out of other people's money and then they come for you," Musk wrote in response to a tweet featuring a templated letter opponents can send to their congressperson. The letter says that although holdings in 401(k) plans are excluded, the proposal takes tax hikes "a step closer to imposing unrealized capital gains tax on the average investor."

As the wealthiest man in the world, however, Musk is far from the average investor, and has seen his net worth increase by some $117 billion in 2021 alone, per Bloomberg's count.

While the proposal has garnered backing from the White House, it has already divided Washington, with some critics calling it unconstitutional, convoluted or unfairly targeting a specific group of people who have contributed to America's economic growth.

Wyden and proponents, meanwhile, say it will help ensure the billionaires pay their fair share of taxes after reports that some of the richest 1% of Americans have legally avoided paying taxes on their wealth gains despite their net worths increasing dramatically -- and at a time of massive wealth inequality in the U.S. that experts have said is exacerbated by America's tax codes being tilted in favor of the wealthy.

Though it currently faces an uphill battle in implementation, here is what to know about the proposed billionaires' income tax.

Who would be hit with the new tax?

The new tax would apply to roughly 700 taxpayers, according to a statement from Wyden's office, or those with more than $100 million in annual income or more than $1 billion in assets for three consecutive years. With a population of 328 million, this means the new tax would impact less than 0.001% of Americans.

The wealth of billionaires tends to be more tied up in stocks compared to working-class Americans. The wealthiest 1% of households in the U.S. own more than half of all the publicly traded stock in the market, according to Federal Reserve data, and the bottom 50% own less than 1%.

Recent investigative reports, including a bombshell leak of tax documents to the nonprofit news organization ProPublica earlier this year, have found that the ultra-wealthy use legal loopholes to avoid paying taxes on their wealth gains -- such as keeping their reported income, and thus income taxes, to just a fraction of what their net worth actually is. Musk, for example, earned a base salary of $0 at Tesla in 2020, according to SEC filings.

The ProPublica report found that while the median American household paid 14% of their income in federal taxes, the wealthiest 25 Americans had an average so-called "true tax rate" of 3.4% of the amount their wealth grew each year between 2014 and 2018.

Wyden alluded to this divide, saying that the Billionaires Income Tax would ensure "billionaires pay tax every year, just like working Americans."

"There are two tax codes in America," Wyden said in a statement accompanying his proposal on Wednesday. "The first is mandatory for workers who pay taxes out of every pay check. The second is voluntary for billionaires who defer paying taxes for years, if not indefinitely."

How does it work?

Under current tax codes, if the value of stocks rises it can lead to swift, multimillion dollar gains in the net worth of the nation's wealthiest individuals -- but they don't have to pay taxes on these wealth gains unless they sell the stocks.

Wyden's proposal would ask billionaires to pay an annual tax on gains or take deductions for losses whether they sell the stocks or not.

"The way the system works today is that if you make a profit on assets that you hold, they're worth more at the end of the year than the beginning. You don't pay tax unless you sell those assets," Howard Gleckman, a senior fellow in the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, told ABC News on Wednesday.

"There are trillions of dollars in increased value of assets that simply go untaxed," Gleckman added. "And that is one big reason for the income inequality, and the fact that the rich have gotten so much richer."

Non-tradable assets like real estate or business interests would not be taxed annually, but when billionaires sell or transfer these non-tradable assets, they would pay a capital gains tax in addition to an interest charge that Wyden's office labels as akin to interest charged on deferred tax.

The interest charge -- or "deferral recapture amount," as Wyden is calling it, would be the amount of interest that would be due on tax owed if the asset had been marked to market each year and the tax had been deferred until sale. The interest rate applied would be 1.22%, per Wyden's office, or the applicable federal short term rate (currently 0.22%) plus one percentage point.

The proposal contains rules to help smooth the transition, such as being able to treat up to $1 billion of tradable stock in a single corporation as a non-tradable asset. It would also let billionaires elect to pay tax over five years the first time the billionaires' tradable assets are marked to market.

The full, 107-page text of the tax proposal can be found here.

Gleckman said he sees potential issues arising if a major asset goes down in value and are calculated as losses by billionaires, and because of the potential for confusion over the valuation of privately held, non-tradable assets.

"The bottom line, the 30,000-foot level, this is a very interesting idea but it is very hard to administer," Gleckman said. "This is not a wealth tax, but it has some of the common administrative problems of a wealth tax -- the biggest being it's hard to value the assets of rich people."

Is it constitutional?

A legal challenge likely looms if the proposal is enacted, and critics have already questioned the constitutionality of taxing unrealized or unsold capital gains.

Under current law, the government has the power to tax "income" due to the 16th Amendment, but new wealth gains are only classified as income when they are realized or sold, not simply held. The Supreme Court in 1920 ruled that stock dividends did not become taxable as income until they were sold or converted.

This definition of income has benefits to working- and middle-class Americans, as they do not have to pay taxes on retirement savings such as their 401(k)s when they increase in value until they cash out.

White House press secretary Jen Psaki, however, signaled that they believe the new tax has legal footing.

When asked about the questionable constitutionality of the tax, Psaki said, "We're not going to support anything we don't think is legal."

"The president supports the billionaire tax," she added. "He looks forward to working with Congress and Chairman Wyden to make sure the highest income Americans pay their fair share."

In a statement to ABC News, Wyden defended his proposal from critics, saying, "Entire sections of the tax code are unconstitutional if this is unconstitutional."

"I can't imagine the Supreme Court wants to give the wealthiest people on earth billions in tax cuts, particularly at a time when so many Americans are losing faith in the Supreme Court," he added.