Blackface 'Jazz Singer' still influencing modern cinema 90 years after release

"The Jazz Singer" premiered Oct. 6, 1927.

— -- It was an era that few of us would recognize today. It was the time of the “flapper girl.” Construction had just begun on Mount Rushmore and Calvin Coolidge was president.

It was 1927, and a film was about to revolutionize the motion picture industry.

The film -- "The Jazz Singer" -- opened in New York City Oct. 6, 1927.

The movie, a musical, marked the beginning of the end for silent films, experts say, as motion pictures called "talkies" started to become the norm. It was not only the first feature-length film to incorporate sound, it also had a recorded musical score that played in conjunction with lip-synchronous singing and speaking.

Cameras made so much noise back then that it was often tough for producers to record the audio for a movie at the same time they recorded the visuals, which is why they recorded the sound separately and later synced it with film. It was a difficult undertaking, and was a huge gamble for Warner Bros. to attempt in "The Jazz Singer." But it paid off.

"It was important how ['The Jazz Singer'] impacted America, not only the medium itself," senior lecturer Marc Lapadula of Yale University's Film Studies program, told ABC News. "If [the sound and film] had not matched, it could have been curtains for Warner Bros."

But the "success" of the film comes with a grain of salt. Warner Bros. played with the numbers to make it look like a huge hit, according to Donald Crafton, a retired professor of film, television and theatre at the University of Notre Dame.

"The box office figures were well below other big hits of the 1927 blockbuster season ... also, there were far more people who saw 'The Jazz Singer' as a silent film, that is, without the Vitaphone soundtrack, than as a sound film, because [Warner Bros.] distributed both versions," Crafton told ABC News. "The studio inflated its reports of box office records by combining revenue for the sound and silent sales."

Crafton contends it "did not start a stampede to sound in Hollywood ... however, Hollywood prefers legends, so ['The Jazz Singer'] will always be venerated as the birth of the talkies."

But Yale’s Lapadula said "The Jazz Singer" was enough of a hit that it influenced other production companies to change their previously released films.

"Films evolved after 'The Jazz Singer,' so that by 1930, it's only the rare film that was going to be a silent film," Lapadula said.

"The Jazz Singer" also ended some careers overnight, experts note.

Many of the actors and actresses who appeared in the popular silent films of the era couldn't deliver lines, and in some cases, couldn't even speak English.

"If you didn't join the sound bandwagon, most of those careers would be gone," Lapadula noted.

In the film, the central character, played by Al Jolson, is of Jewish heritage from the Lower East Side of Manhattan. The character's father is a cantor at a synagogue and wants his son to carry on the tradition.

But Jolson's character, named Jakie Rabinowitz, is more interested in "modern" music, like jazz. Horrified by his son’s choices, Jakie's father sends him away and refuses to see him again.

Jakie changes his name to Jack Robin and pursues his dreams. Spoiler alert: Jack Robin eventually reconciles with his family.

Professor Crafton described "The Jazz Singer" as "a very poignant story about a family torn apart by generational conflict."

Despite the movie's iconic standing, however, it is not without controversy.

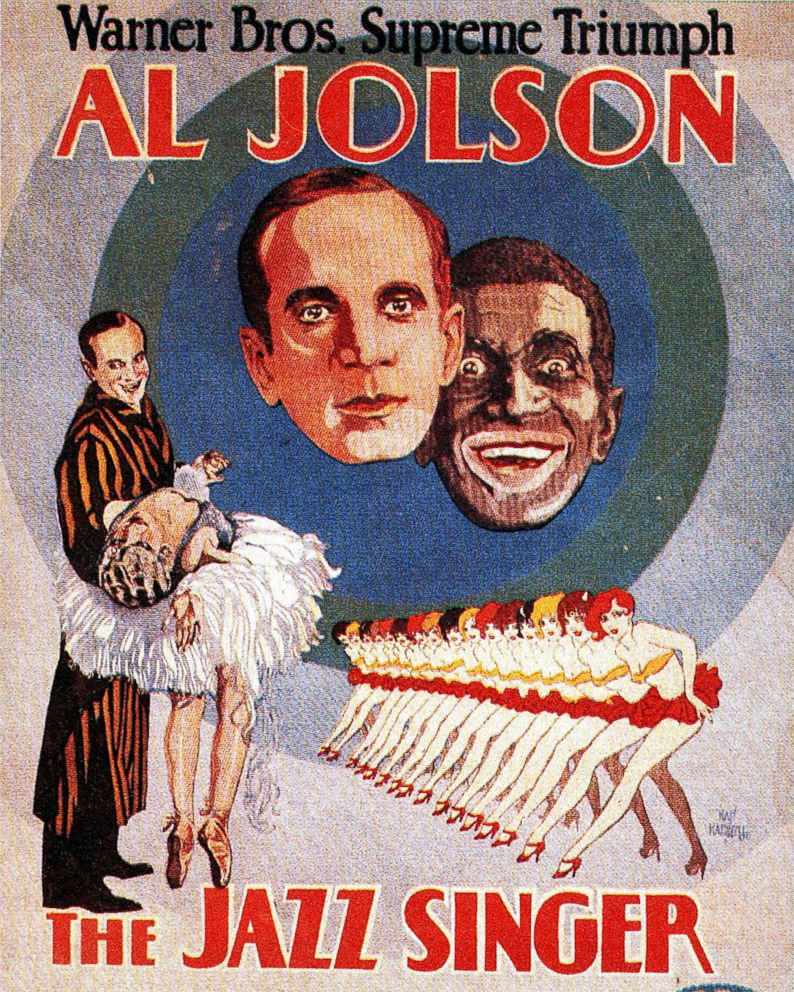

As was common at the time, Jolson’s wears blackface during his performance. Though the practice might appear racist by modern-day viewers, Lapadula cautions people not to jump too quickly to that conclusion without understanding the historical context of the use of blackface in the film.

"[Jolson] wasn't hyperbolizing, he wasn't making fun of, he wasn't going for laughs, he was quite sincere to bring jazz into the mainstream," Lapadula said.

Indeed, Lapadula believes Jolson helped blur the color line with his portrayal in "The Jazz Singer."

"Behind this face was a Jewish man," Lapadula notes. "He needs this blackface to express a new Jewishness."

Crafton agreed that "there was a propensity for these entertainers to be assimilated Jewish immigrants, perhaps because there was some kinship felt with marginalized African-Americans as neighbors in the melting pot.”

That Jolson was so popular then, and because blackface in films was so common, "generally, at that time [it] would not have been considered out of the ordinary or offensive,” Crafton said.

No one seemingly bothered to ask the country’s black population what they thought, he added.

Lapadula contends that Jolson's rendition helped pave the way for African-American actors. Jolson was a civil rights advocate, often backing projects by black artists, including playwright Garland Anderson.

"The first African-American playwright to get his drama on Broadway was [Anderson, and the drama was] about a black bellhop that was accused of raping a white woman," Lapadula recalled. "Jolson sponsored it. He was a champion of civil rights."

A play like that would have never gotten on Broadway without people like Jolson supporting it, Lapadula says.

"With that kind of power, you can kind of do what you want, and [Jolson] did it for good," Lapadula said.

Crafton says "The Jazz Singer” was crucial in advancing the discussion of race in society.

"'The Jazz Singer' was an important story about ethnic, racial and religious assimilation," Crafton told ABC News. "It communicated many of the anxieties of its day, just as films like 'Blackboard Jungle,' 'The Godfather' and 'Boyz in the Hood' did in theirs."

For all its toeing the line of controversy, "The Jazz Singer" remains a crucial influencer of film beyond bringing jazz music to the audience of people who normally experience it.

"’The Jazz Singer’ is a very crude movie," Lapadula said. "It's in the primordial stages, but it was that pivotal step that had to be taken. By 1930, it signaled the start of modern cinema."

Because sound was then being incorporated, for instance, actors couldn’t use their exaggerated way of pantomiming anymore. The new way of acting focused on being able to deliver lines effectively and to find power in the subtleties.

"Because of the invention of sound now for the first time in the history of cinema, we can hear the power of silence," Lapadula said.

It’s sometimes what is not said that can be the most profound part of film, Lapadula noted.

"Sometimes, dialogue deflates the raw power of the moment," Lapadula said.

So not only did "The Jazz Singer" bring sound to silent films, it empowered silence in talkies.

But beyond the use of sound, the themes addressed in the motion picture are still relevant today.

"Father versus son, the old ways versus the new, strong religious or patriotic beliefs versus permissiveness; these are all still viable themes and interesting stories," Crafton said. "Because they’re still relevant and define us as families and as a nation."